Pratite promene cene putem maila

- Da bi dobijali obaveštenja o promeni cene potrebno je da kliknete Prati oglas dugme koje se nalazi na dnu svakog oglasa i unesete Vašu mail adresu.

51-70 od 70 rezultata

Prati pretragu "luciano"

Vi se opustite, Gogi će Vas obavestiti kad pronađe nove oglase za tražene ključne reči.

Gogi će vas obavestiti kada pronađe nove oglase.

Režim promene aktivan!

Upravo ste u režimu promene sačuvane pretrage za frazu .

Možete da promenite frazu ili filtere i sačuvate trenutno stanje

Aktivni filteri

-

Tag

Knjige

-

Kolekcionarstvo i umetnost chevron_right Knjige

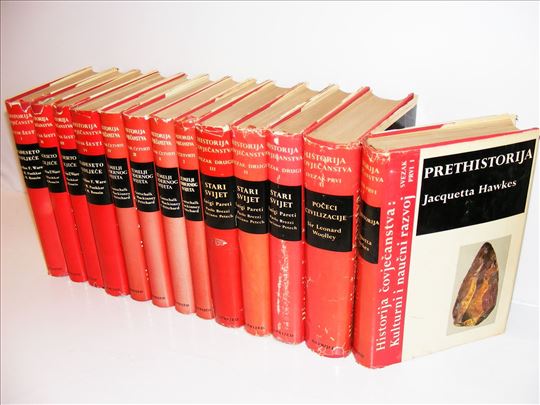

Historija čovječanstva Kulturni i naučni razvoj 1-13 Pripremljeno pod pokroviteljstvom UNESCO-a. Prethistorija i Počeci civilizacije Prethistorija, svezak prvi-knjiga prva Počeci civilizacije, svezak prvi-knjiga druga Jacquetta Hawkes: Prethistorija Leonard Wooley: Počeci civilizacije. Stari Svijet, svezak drugi-knjiga prva Stari Svijet, svezak drugi-knjiga druga Stari Svijet, svezak drugi-knjiga treća Svezak drugi - Luigi Pareti, Paolo Brezzi, Luciano Petech: Stari svijet: Stari svijet od 1200. do 500.god.pr.n.e. Stari svijet od 500.god. pr.n.e. do nove ere Stari svijet od početka nove ere do 500.god. Temelji modernog svijeta, svezak četvrti-knjiga prva Temelji modernog svijeta, svezak četvrti-knjiga druga Temelji modernog svijeta, svezak četvrti-knjiga treća Temelji modernog svijeta, svezak četvrti-knjiga četvrta Svezak četvrti - Louis Gottschalk, L.C.Mackinney, E.H.Prichard: Temelji Modernog svijeta 1300-1775: Uvod, poltička, ekonomska i društvena pozadina - važniji vjerski događaju 1300-1500 Važniji vjerski događaju 1500-1775, politička i društvena misao (1300-1775) Pismeno priopćavanje i lijepa književnost, likovna umjetnost i glazba, znanost i tehnologija između 1300 i 1530 Znanost i tehnologija - tehnologija i društvo - školstvo Dvadeseto stoljeće, svezak šesti-knjiga prva Dvadeseto stoljeće, svezak šesti-knjiga druga Dvadeseto stoljeće, svezak šesti-knjiga treća Dvadeseto stoljeće, svezak šesti-knjiga četvrta Svezak šesti - Ca

-

Kolekcionarstvo i umetnost chevron_right Knjige

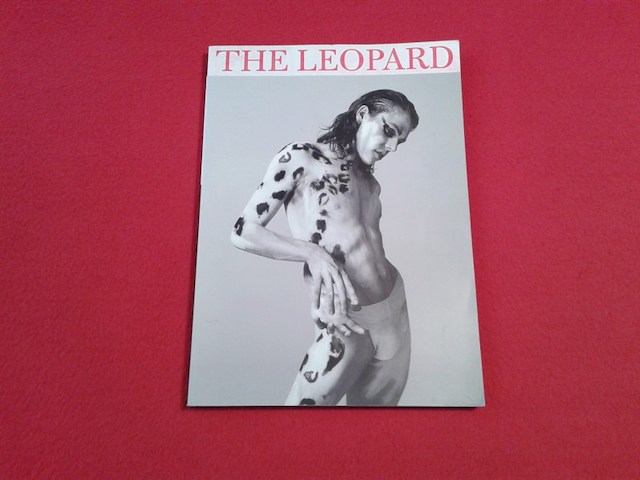

The Leopard is a new limited edition annual magazine from Alister Mackie, Jamie Andrew Reid and Liam Hess. Povez: broširan Broj strana: 196 Ilustrovano. Veliki format: 27,5 x 38,5 cm Ograničeni tiraž: 1500 primeraka Gornji ćoškovi poslednjih 30-ak listova malo dokačeni vodom, listovi su na tim mestima malo talasasti i to je to. Ako se ovo zanemari časopis je veoma dobro očuvan. Ređe u ponudi. A scrapbook of archival material, new photography and rare interviews, The Leopard covers cult artists from generations past that might otherwise be overlooked, alongside emerging creatives working in their tradition today. A celebration of queer life in all of its creativity, sensuality and DIY glamour – from political activists to painters, poets to pin-ups – the features and photo stories are linked by the recurring presence of the magazine’s mascot, the elusive creature of the leopard. Issue contributors include: Ryan McGinley, Amelia Abraham, Andrej Dubravsky, Peter Bebjak, Liam Hess, Ibrahim Kamara, Kristin-Lee Moolman, Thiago Dias, Michael Bailey-Gates, Ethan James Green, Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, Devin Barrett, Luciano Castelli, Tim Blanks, Archivio Fotografico Franco Maria Ricci, Jacopo Bedussi, Brett Lloyd, Alister Mackie, Sharna Osborne, Félix Ledru & Harley Weir, Jack Taylor Lovatt, Sayat-Nova, Christopher Davidson, Mark Segal, Sarah Piant Adosi, and more. (S-1)

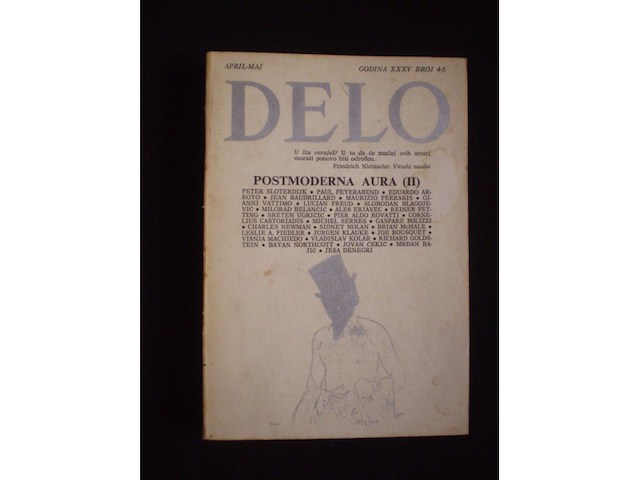

DELO : POSTMODERNA AURA (II) - GODINA XXXV BROJ 4-5 autori: Peter Sloterdijk - Paul Feyerabend - Eduardo Arroyo - Jean Baudrillard - Maurizio Ferraris - Gianni Vattimo - Lucian Freud - Slobodan Blagojević - Milorad Belančić - Aleš Erjavec - Reiner Fetting - Sreten Ugričić - Pier Aldo rovatti - Cornelius Castoriadis - Michel Serres - Gaspare Polizzi - Charles Newman - Sidney Nolan - Brian McHale - Leslie A. Fiedler - Jurgen Klauke - Joe Bousoquet - Višnja Machiedo - Vladislav Kolar - Richard Goldstein - Bayan Northcott - Jovan Čekić - Mrđan Bajić - Ješa Denegri Mek povez, 388strana, izdavač: NOLIT - Beograd

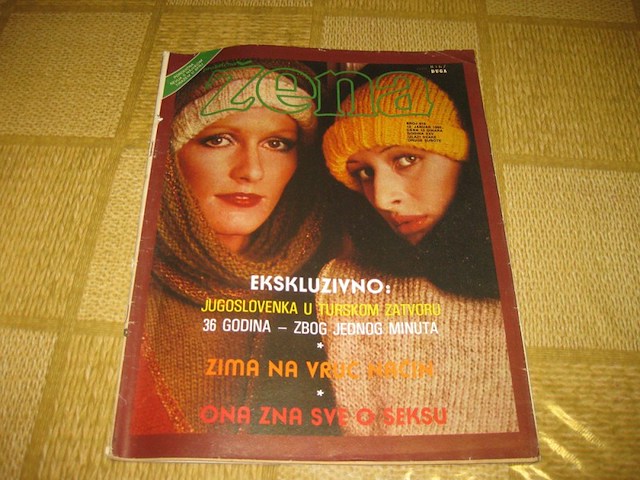

Praktična žena broj 615 (1980.) NEMA krojni tabak i 3 lista gde je bio vez! strana: 96 Iz sadržaja: Naslovna: ? Naš gost: Dr Lučiano Motroni, hirurg na Kosovu Radni staž za ženu (na dve strane) Ljubljana: Darinka Mravlje osuđena u Turskoj na 36 godina zatvora (na 3 strane i 3 fotografije) Izložba: Jozo Janda U ulozi reportera: Gertruda Munitić Feljton: Jedno vreme, jedna žena - Mir-Jam 6.deo (Dušan Savković) Strip: Maja (Askanio Popović) Voždovac: Dom Pionira je održao Peti decembarski turnir u ritmičko-sportskoj gimnastici Roman u nastavcima: Divlja slatka ruža - Rozmeri Rodžers 13.deo Nagrada `Gordana Boneti` (spikerke i voditeljke na 3 strane) Modni kreator: Gradimir Buđevac (modeli ?) Moda: Moda za sve, Stil zvani romantika (modeli ?) Narodni vez: Prsluk od šamije Uradi sama: Ukrasi od kanapa Uređenje stana: Jednosoban stan za troje Pletenje: Jakna u plavim tonovima Vez, vezenje, kukičanje: Kukičana kragna Kuvar: Recepti Doktor u kući Skladište: Magazini 53 Ocena: 3+. Vidi slike. Tagovi: Vez, vezenje, kukičanje, krojenje, štrikanje, heklanje, pletenje... Težina: 200 grama NOVI CENOVNIK pošte za preporučenu tiskovinu od 01.04.2021. godine. 21-50 gr-85 dinara 51-100 gr - 92 dinara 101-250 gr - 102 dinara 251-500 gr – 133 dinara 501-1000gr - 144 dinara 1001-2000 gr - 175 dinara Za tiskovine mase preko 2000 g uz zaključen ugovor, na svakih 1000 g ili deo od 1000 g 15,00 +60,00 za celu pošiljku U SLUČAJU KUPOVINE VIŠE ARTIKLA MOGUĆ POPUST OD 10 DO 20 POSTO. DOGOVOR PUTEM PORUKE NA KUPINDO. Pogledajte ostale moje aukcije na Kupindo http://www.kupindo.com/Clan/Ljubab/SpisakPredmeta Pogledajte ostale moje aukcije na Limundo http://www.limundo.com/Clan/Ljubab/SpisakAukcija

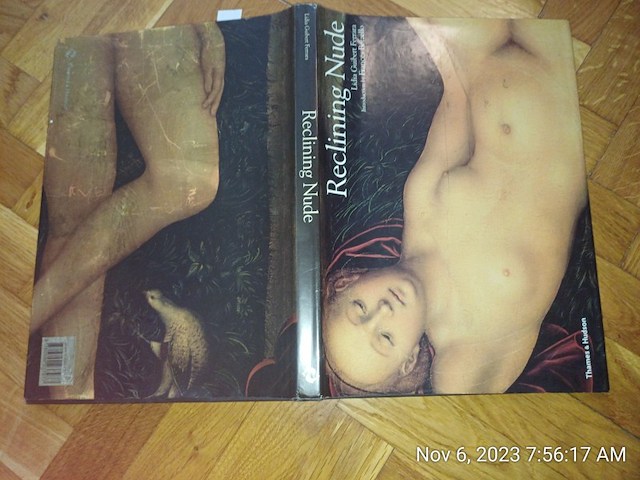

KSČ64) Sensuous, voluptuous, provocative - the female form has inspired artists for centuries, making it perhaps the most popular subject in the history of painting. Since Giogione`s `Sleeping Venus`, the first notable female nude in Western painting, artists have focused on the infinite possibilities of the representation of the female body. Featuring full-page illustrations of masterpieces of the genre - from Titian`s `Venus of Urbino` to Manet`s `Olympia`, from Invres` `Large Odalisque` to Lucian Freud`s `Naked Girl` - this volume provides a tour of Western society`s ever-changing visions of beauty and repose.

=====================ஜ۩۞۩ஜ===================== + ────────▄ █▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀▀█ ────▄▄██▌█►►►Šaljem brzom poštom ▄▄▄▌▐██▌█►►►ili lično preuzimanje █████████►►►na adresi koju dam u poruci ░░████████▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄▄█ ▀▀@▀▀▀▀▀▀▀@@▀▀▀▀▀▀@@▀▀▀▀▀▀@@▀< *¨ `*• . ¸ ¸ . • *´ ¨ `*• . ¸ ¸ . • ➤➤➤ Alan Ford trobroj - broj 1 - Prva edicija u nizu trobroja, Raritet ◄◄◄ Probajem prvu svesku - trobroj koja svedoči o životu najtajnije od svih tajnih grupa Sveska je korišćena ali je u dobrom opštem stanju, redak je primerak. Prva sveska trobroj od 13 trobroja: ➤ GRUPA TNT ➤ SUPLJI ZUB ➤ OPERACIJA FRANKENSTEIN Superstrip - Zagreb preveo Nenad Briksi 384 strane ➤ : Parodija na Džejmsa Bonda Autori „Alana Forda“ su scenarista Maks Bunker, pravim imenom Lučiano Seki i crtač Magnus, za poreske organe Roberto Raviola. Oni su 1969. godine, nakon par godina planiranja, počeli sa izdavanjem humorističkog stripa koji je prvobitno bio zamišljen kao parodija na Džejmsa Bonda. Grupa priučenih tajnih agenata okupljena oko paralizovanog starca u kolicima i neodredive dobi je bila urnebesni antipod Džejms Bondu. „Super Strip Maksi“ će doživeti 13 brojeva i od magazina potpuno posvećenog „Alan Fordu“ evoluiraće u strip reviju sa raznovrsnim izborom svetskih i domaćih stripova i naposletku se ugasiti krajem 1989. godine. Svoje mesto je ustupio trobroj izdanjima. Sa njima se i po četvrti put u dvadeset godina krenulo u obnavljanje gradiva. Početna ideja sa izdavanjem epizoda koje čitaoci najviše traže je odmah u startu pretvorena u hronološko objavljivanje po tri epizode u jednoj svesci. Ukupno je izašlo 13 trobroja, a poslednji je izašao u trenutku kada je građanski rat uveliko besneo. Sveska broj 448 sa epizodom „Doktor Rakar“ je bila poslednja koju je objavio „Vjesnik“ u regularnoj ediciji. Za sva dodatna pitanja, slobodno se obratite putem poruke. Pogledajte i moje druge licitacije na adresi ➷➷➷ http://www.limundo.com/Clan/Dr.Sloba/SpisakAukcija Kao i prodaje na adresi ➷➷➷ http://www.kupindo.com/Clan/Dr.Sloba/SpisakPredmeta Hvala na poseti i srećna kupovina!!! =====================ஜ۩۞۩ஜ=====================

-

Kolekcionarstvo i umetnost chevron_right Knjige

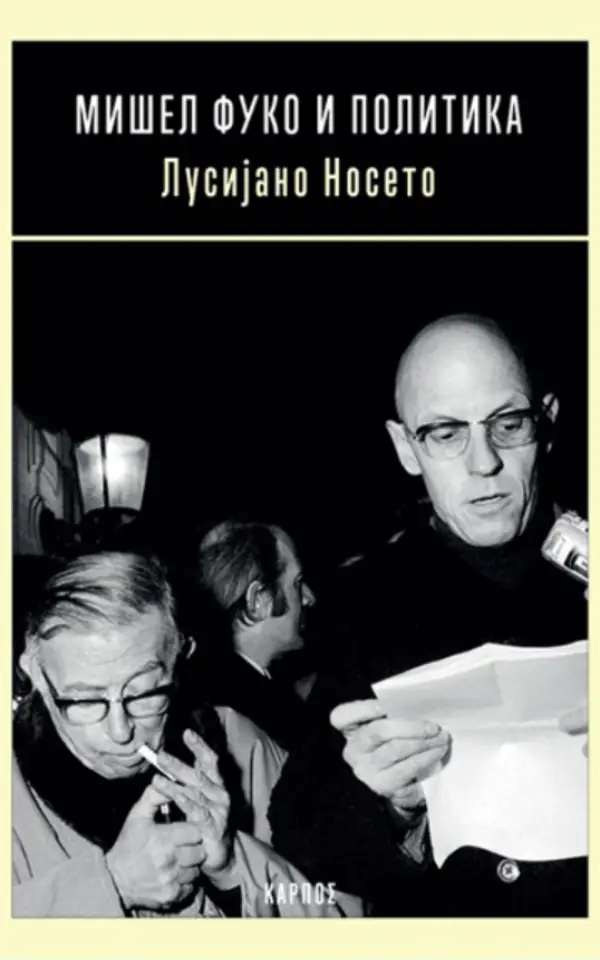

U Fukou će istovremeno živeti dve rastrzane ličnosti. Prva je ličnost akademika kojeg su usmerili principi vrednosne neutralnosti i normativne sterilnosti, posvećenog uništavanju dokaza i kritici svega postojećeg. Druga je ličnost militantna, upletena u političke borbe, koja prihvata snažne normativne kompromise. Smatramo da je, uz određene manje korekcije, ovo pravilno vrednovanje teorijsko-praktičnog stava Mišela Fukoa i da je on sam eksplicitno ukazivao na ovu distancu između svog akademskog i aktivističkog delovanja. Lusijano Noseto U poslednjoj deceniji, Mišel Fuko je u više navrata izbijao na čelo internacionalnih citatnih indeksa. Razlog za češće i mnogobrojnije pozivanje na njegova dela ne leži samo u popularnosti njegove misli u međunarodnoj akademskoj zajednici, njenom bogatstvu i provokativnosti, nego i u jednom konkretnom razlogu – objavljivanju njegovih predavanja na Кolež de Fransu, najpre na francuskom, a potom u brojnim prevodima koji su objavljeni u protekle dve decenije. Fuko i politika, knjiga Lusijana Noseta, mladog argentinskog filozofa, jedna je u nizu studija koje ne bi mogle nastati bez tih, danas dostupnih predavanja, pre svega kursa Treba braniti društvo iz 1976, i Rađanje biopolitike. (1978–1979), a u manjoj meri Bezbednost, teritorija, stanovništvo (1977–1978) i Кazneno društvo. (1972–1973). Noseto govori o Fukoovim viđenjima evropske tradicije političke filozofije, tehnikama vladanja, raznovrsnim tipovima moći, njegovim konceptima biomoći, biopolitike i guvernmentaliteta, koji su u delima objavljenim za Fukoovog života bili šturo objašnjeni, te su katkad izazivali nesporazume i neopravdane kritike. Noseto je posebno zainteresovan za to u kojoj meri je Fukoova misao upotrebljiva za konkretne političke agende, imajući u vidu argentinske političke prilike. Lusijano Noseto (Luciano Nosetto) rođen je 1979. godine u Argentini. Doktorirao je na Univerzitetu u Buenos Ajresu. Bavi se prevashodno savremenom političkom teorijom, naročito Hanom Arent, Mišelom Fukoom, Кarlom Šmitom i Leom Štrausom. Studija „Mišel Fuko i politika“, objavljena na španskom 2014, izuzetno je dobro primljena u stručnim krugovima u nagrađivana u Argentini. Noseto piše o političkoj filozofiji Mišela Fukoa i prvi put sistematizuje Fukoove brojne političke ideje i uvide; otuda je njegov studiozni rad umnogome pionirski i redak u međunarodnoj bibliografiji.

Nova knjiga, necitana, nema posvete. Mišel Fuko i politika - Lusijano Noseto Izdavač: Karpos Godina izdanja: 2022 Broj strana: 250 Format: 20 cm Povez: Broširani U Fukou će istovremeno živeti dve rastrzane ličnosti. Prva je ličnost akademika kojeg su usmerili principi vrednosne neutralnosti i normativne sterilnosti, posvećenog uništavanju dokaza i kritici svega postojećeg. Druga je ličnost militantna, upletena u političke borbe, koja prihvata snažne normativne kompromise. Smatramo da je, uz određene manje korekcije, ovo pravilno vrednovanje teorijsko-praktičnog stava Mišela Fukoa i da je on sam eksplicitno ukazivao na ovu distancu između svog akademskog i aktivističkog delovanja. Lusijano Noseto U poslednjoj deceniji, Mišel Fuko je u više navrata izbijao na čelo internacionalnih citatnih indeksa. Razlog za češće i mnogobrojnije pozivanje na njegova dela ne leži samo u popularnosti njegove misli u međunarodnoj akademskoj zajednici, njenom bogatstvu i provokativnosti, nego i u jednom konkretnom razlogu – objavljivanju njegovih predavanja na Кolež de Fransu, najpre na francuskom, a potom u brojnim prevodima koji su objavljeni u protekle dve decenije. Fuko i politika, knjiga Lusijana Noseta, mladog argentinskog filozofa, jedna je u nizu studija koje ne bi mogle nastati bez tih, danas dostupnih predavanja, pre svega kursa Treba braniti društvo iz 1976, i Rađanje biopolitike. (1978–1979), a u manjoj meri Bezbednost, teritorija, stanovništvo (1977–1978) i Кazneno društvo. (1972–1973). Noseto govori o Fukoovim viđenjima evropske tradicije političke filozofije, tehnikama vladanja, raznovrsnim tipovima moći, njegovim konceptima biomoći, biopolitike i guvernmentaliteta, koji su u delima objavljenim za Fukoovog života bili šturo objašnjeni, te su katkad izazivali nesporazume i neopravdane kritike. Noseto je posebno zainteresovan za to u kojoj meri je Fukoova misao upotrebljiva za konkretne političke agende, imajući u vidu argentinske političke prilike. Lusijano Noseto (Luciano Nosetto) rođen je 1979. godine u Argentini. Doktorirao je na Univerzitetu u Buenos Ajresu. Bavi se prevashodno savremenom političkom teorijom, naročito Hanom Arent, Mišelom Fukoom, Кarlom Šmitom i Leom Štrausom. Studija „Mišel Fuko i politika“, objavljena na španskom 2014, izuzetno je dobro primljena u stručnim krugovima u nagrađivana u Argentini. Noseto piše o političkoj filozofiji Mišela Fukoa i prvi put sistematizuje Fukoove brojne političke ideje i uvide; otuda je njegov studiozni rad umnogome pionirski i redak u međunarodnoj bibliografiji.

Autor - osoba Blaga, Lucian Naslov Božja senka / Lučijan Blaga ; [izbor, prevod i pogovor Petru Krdu] Vrsta građe poezija Jezik srpski Godina 1995 Izdavanje i proizvodnja Beograd : Rad, 1995 (Beograd : Zuhra) Fizički opis 76 str. ; 18 cm Drugi autori - osoba Cârdu, Petru, 1952-2011 = Krdu, Petru, 1952-2011 Cioran, Emil, 1911-1995 = Sioran, Emil, 1911-1995 Zbirka Reč i misao ; knj. 462 Napomene Vedrina svetlo-tamnog i Lučijan Blaga zaštićen njome / Petru Krdu: str. 63-68 Unutrašnji stil Lučijana Blage / Emil Sioran: str. 69-73. Predmetne odrednice Blaga, Lučijan, 1895-1961 Lučijan Blaga (1895–1961) je jedan od stubova nosača rumunske kulture i duhovnosti čije ime stoji odmah posle velikog Mihaila Emineskua (1850–1889). Snažni glas iz Transilvanije, poreklom iz Erdelja, iz okoline Sebeša, 1920. godine doktorirao je filozofiju u Beču, ali je ubrzo pokrenuo književni časopis „Misao“ i time odredio svoj pesnički put. Neko vreme radio je u diplomatiji u Varšavi, Pragu, Beču, Brnu, a član Rumunske akademije postao je 1937. godine. Posle Drugog svetskog rata, silom prilika, povukao se u unutrašnje izgnanstvo i posvetio isključivo pisanju/mišljenju... MG95 (L)

PRVI SVETSKI RAT: Lučijan Boja Naslov Prvi svetski rat : kontroverze, paradoksi, reinterpretacije / Lučijan Boja ; [preveo s rumunskog Dragan Stojanović ; redakcija prevoda Stevan Bugarski] Jedinstveni naslov Primul rǎzboi mondial. srpski jezik Vrsta građe stručna monografija URL medijskog objekta odrasli, ozbiljna (nije lepa knjiž.) Jezik srpski Godina 2015 Izdavanje i proizvodnja Novi Sad : Prometej ; Beograd : Radio-televizija Srbije, 2015 (Novi Sad : Prometej) Fizički opis 106 str. ; 21 cm Drugi autori - osoba Stojanović, Dragan = Stojanović, Dragan Bugarski, Stevan, 1939- = Bugarski, Stevan, 1939- Zbirka Edicija Srbija 1914-1918 ; ǂkolo ǂ2, ǂknj. ǂ4 ISBN 978-86-515-1023-9 (karton) Napomene Prevod dela: ǂPrimul ǂrǎzboi mondial / Lucian Boia Tiraž 1.000 Beleška o autoru: str. 105-106 Napomene i bibliografske reference uz tekst. Predmetne odrednice Prvi svetski rat 1914-1918 Knjige Lučijana Boje su više nego polemička ispitivanja u smislu demitologizacije i otklanjanja zajedničkih mesta u istoriji i, implicintno, u rumunskom mentalitetu. Realni ulog je pisanje zajedničke evropske istorije, oslobođen predrasuda i opšteprihvaćenih teorija. Ova je knjiga nužni i jasni sintetički izraz dosadašnjih autorovih ideja, a glavna joj je tematika ‘utemeljujući događaj sveta u kojem živimo’. Po svojoj moralnoj problematici, po svom zamahu i po svojim katastrofalnim posledicama, koje su se neposredno materijalizovale u drugoj svetskoj konflagraciji, Prvi svetski rat ostaje jedna od najprostresnijih drama novije istorije. A Versajski sistem ostaje čin rođenja sadašnje Evrope Potpuno nova, nekorišćena knjiga. bs

Dvojezična knjiga na rumunskom i engleskom, prepuna sjajnih ilustracija, karikatura i crteža. The Norma d\`Lux art album (Brumar house, Timişoara, Point collection, 2016) contains a selection of the more than 700 drawings that form the online project of the Balamuc group entitled Norma – a drawing per day/radical take out of Pi, organized in depending on the theme in 13 chapters dealing with various subjects, about art and society, from social to political. The bilingual album has two prefects (Dana Sarmeș and Dan Perjovschi), 256 unnumbered pages, 1400 g, cover and overcover, and is published through the efforts of the Contrasens Association, with the financial support of AFCN. Norma d\`Lux illustrates Balamuc`s main project, used mostly to try out ideas and vent frustrations from every day in almost anonymous drawings posted online, more or less daily, on the Facebook page, since 2014. Other visual artists were invited to participate in this project, whose drawings are reproduced in the Supadupa Invites chapter: Sorina Vazelina, pnea, Neuro Book, Ileana Surducan, Maria Surducan, Mimi Ciora, Mircea Popescu, Dana Catona, Monotremu, Ioana Vreme Moser, Lucian Popovici, Aitch, Saddo, Katja Spitzer, Gloria Vreme Moser, Dan Perjovschi and Suzana Dan. Više informacija: https://romaniandesignweek-ro.translate.goog/portofoliu/norma-dlux?_x_tr_sl=ro&_x_tr_tl=en&_x_tr_hl=en-US# Odlično očuvano, jedino je dustjacket malo cepnut prilikom transporta, sve ostalo je kao novo 2016. godina, Brumar 254 strane Tvrd povez Veliki format

U dobrom stanju! Lucian Goldman (fr. Lucien Goldmann, 1913, Bukurešt, Rumunija - 1970, Pariz, Francuska) - francuski filozof i sociolog, teoretičar marksizma, osnivač genetskog strukturalizma. Rođen je u rumunskoj jevrejskoj porodici. Goldman je studirao na Univerzitetu u Bukureštu, a takođe godinu dana na Bečkom univerzitetu, gde je jedan od teoretičara austro-marksizma, filozof Mak Adler, imao veliki uticaj na njega. 1934. godine dobio je diplomu iz Sorbone. Iste 1934. godine izbačen je iz podzemnog komunističkog saveza omladine Rumunije zbog `trockizma`. Lucien Goldman je 1942. emigrirao u Švajcarsku, gde je radio kao asistent Jean Piaget-a i pridružio se njegovom istraživanju u genetskoj epistemologiji. Godine 1945. preselio se u Pariz, gde je živeo do kraja svog života. Lucien Goldman je bila zaposleni u Nacionalnom centru za naučno istraživanje, kao i profesor na Višoj školi društvenih nauka i na Sorboni. Radio je kao direktor Praktične škole za viši studij 1959-1964. Direktor Centra za sociologiju književnosti od 1964. Ovaj istraživački centar organizovan je na njegovu inicijativu na Slobodnom univerzitetu u Briselu. Goldmanova biografija poslužila je kao izvor za roman francuske književnice i filozofa Julije Kristeve `Samurai` (1990). Naučna aktivnost Na Goldmana je snažno uticao ne-marksizam. Posebno važno za oblikovanje filozofskog pogleda na svet bilo je rano delo George Lukacsa. Na Goldmana je uticala i genetska psihologija Žana Piageta. Goldmanova glavna dela posvećena su istoriji zapadnoevropske filozofije i njenim odnosima sa kulturnim i društvenim pojavama. Goldmanova knjiga „Tajni Bog“ (1955) posvećena je uporednoj analizi filozofskih i religijskih pogleda Blaisa Pascala, Jansenizma i Jeana Racinea.

U dobrom stanju Éditeur : Maison des Sciences de l`Homme (30 octobre 2008) Langue : Français Broché : 248 pages Poids de l`article : 422 g Dimensions : 15 x 1.5 x 23 cm Alors qu`elle s`interroge, se regarde et se raconte depuis des siècles, l`Europe demeure perplexe au miroir de ses inépuisables productions. Elle est à l`étroit dans les paragraphes étriqués des documents juridiques, elle tend à se soustraire aux appropriations idéologiques de toutes obédiences, dépasse toujours les images d`elle-même qu`elle crée sans relâche, échappe à sa propre histoire comme à ses historiens, à ses géographes et à tous ceux qui s`efforcent de la définir. Mais elle offre à l`expérience et à l`imagination des hommes la richesse infiniment diversifiée de son patrimoine. S`il est encore et toujours difficile de dire l`Europe, du moins peut-on la percevoir et la toucher, surtout en ces lieux singuliers mais innombrables où se livre au regard et à l`esprit un surcroît de sens. Frontières, carrefours, passages, noeuds urbains, vastes plaines, lieux de commémoration ou de mémoire : ce sont quelques-uns d`entre eux qui ont inspiré les auteurs de cet ouvrage. Dire l`Europe, sous leurs plumes croisées, c`est la redire sans cesse dans la multiplicité de ses manifestations particulières. Stella Ghervas est chargée de recherche en histoire à l`Institut universitaire de hautes études internationales de Genève. François Rosset est professeur de littérature et culture françaises à l`Université de Lausanne et à l`Ecole polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne. Avec les contributions de : Wladimir Berelowitch, Denis Bertholet, Lucian Boia, Sofia Dascalopoulos, Pascal Dethurens, Silvio Guindani, Olga Inkova, Lubor Jilek, Bertrand Lévy, Krzysztof Pomian, René Sigrist, Luc Weibel, Eric Widmer

35. SALON ARHITEKTURE Beograd, 27. mart - 30. april 2013. JOŠ UVEK IMAMO ARHITEKTURU Urednik kataloga - Ljiljana Miletić Abramović Autori tekstova - Ljiljana Miletić Abramović, Slobodan Danko Selinković, Maša Bratuša Prevod - Biljana Velašević, Vladimir Abramović Izdavač - Muzej primenjene umetnosti, Beograd Godina - 2013 228 strana 26 cm ISBN - 978-86-7415-161-7 Povez - Broširan Stanje - Kao na slici, tekst bez podvlačenja AUTORI ZASTUPLJENI U KATALOGU: Zoran Abadić, Dušan Milovanović, Jelena Bogosavljević, Jelena Zagorac, Milan Karaklić, Nikola Žikić, Dijana Adžemović Anđelković Borislav Petrović, Ivan Rašković, Nikola Stojković, Đorđe Alfirević, Nikola Andonov, Vladimir Anđelković, Milica Apostolović, Marijana Kaštelan, Ivana Ilić, Jelena Vučić, Lidija Kljaković, Damjan Jovanović, Miloš Grbić, Tatjana Babić, Dejan Babović, Ljiljana Bakić, Nikola Baković, Milica Baludžić, Aladin Baljinac, Lazar Belić, Ivan Benussi, Danlo Beronja, David Bilobrk, Aleksandar Bobić, Đorđe Bobić, Divna Bogdanović, Veliborka Bogdanović, Aleksandar Bogojević, Milica Bogojević-Bobić, Jelena Bogosavljević, Petar Bojović, Milan Božić, Jelena Brajković, Marko Brkić, Andreja Buđevac, Saša Buđevac, Ksenija Bulatović, Morten Bulow, Nikola Cakić, Miljan Cvijetić, Žarko Ćajić, Nataša Ćuković Ignjatović, Milica Dejanović, Bojana Dončevski, Milan Dragić, Maja Dragišić, Jasna Drakulović, Vladan Drndarević, Saša Đak, Vladan Đokić, Ljiljana Đukanović, Miloš Đurasinović, Milan Đurić, Vanja Enbulajev, Davor Ereš, Đorđe Gec, Nevena Pivić, Vanja Otašević, Zorana Vasić, Ljubiša Folić, Srđan Gavrilović, Nebojša Glišić, Milka Gnjato, Milica Golić, Miloš Grbić, Sanjin Grbić, Jovan Grbović, Bojan Čoti, Danilo Kordulup, Jasmina Hadžiahmetović, Cvjetković Miroslav, Danica Đorđević, Jelena Milojković, Igor Pantelić, Radoslav Ilić, Mirela Čoban, Nikola Šćekić, Dušan Ignjatović, Ivana Ilić, Relja Ivanić, Jelena Ivanović Vojvodić, Nataša Janković, Jovana Jelisavac, Aleksandar Joksimović, Damjan Jovanović, Goran Jovanović, Natalija Jovanović, Milica Jovanović Popović, Slobodan Jović, Anđela Karabašević, Milan Karakli, Marijana Kaštelan, Miroslav Kaštelan, Milena Katić, Jasna Kavran, Aleksandar Keković, Željko Kerleta, Lidija Kljaković, Aleksandar Knežević, Nemanja Kocić, Ana Raković, Mladen Pešić, Milorad Pejanović, Miloš Komlenić, Slaviša Kondić, Dragana Konstantinović, Ivan Kostić, Bojana Kovač Đurasinović, Ana Kovencz-Vujić, Jelena Krstović Nikolić, Spasoje Krunić, Vladimir Kulić, Tamara Kuljanin, Lazar Kuzmanov, Olga Lazarević, Selma Lazović, Zoran Lazović, Jana Lipkovski, Peter Lohr, Darija Ljubić Vojinović, Ivan Ljubić, Vanja Enbulajev, Vladimir Radulović, Nikola Stevanović, Vojislav Stevanović, Predrag Maksić, Slobodan Maldini, Anđelka Mandić-Milutinović, Čarna Marević, Goran Ivo Marinović, Dragan Marković, Iva Marković, Srđan Marlović, Marko Marović, Marija Martinović, Nikola Martinović, Marija Miković, Dejan Milanović, Duška Milanović, Branislav Milenković, Jelisaveta Milenković, Vladimir Milenković, Dejan Miletić, Jovana Miletić, Katarina Miletić, Nemanja Miličić, Miloš Milojević, Slađana Milivojević Milica Milojević, Aleksandar Milojković, Ivan Milošević, Dušan Milovanović, Vasilije Milunović, Predrag Milutinović, Dejan Miljković, Milutin Miljuš, Petar Mitković, Jelena Mitrović, Jovan Mitrović, Vladimir Mitrović, Maroje Mrduljaš, Duška Mrvoš, Vesna Nadaždin Ljubičić, Danilo Nedeljković, Saša Nedeljković, Dušan Nenadović, Milica Nešovanović, Aleksandra Nikitin, Goran Nikolić, Jelena Nikolić, Marko Nikolić, Vojislav Nikolić, Dijana Novaković Nikola Novaković, Ivan Obradović, Milena Obradović, Milorad Obradović, Siniša Obradović, Anđelina Ošap, Jelena Pančevac, Ana Panić, Vanja Panić, Ksenija Pantović, Vladimir Paripović, Miloš Paunović, Ranko Pavlović, Milorad Pejanović, Malden Pešić, Miroslava Petrović Balubdžić, Borislav Petrović, Marjan Petrović, Marko Petrovi, Milica Pihler, Tamara Popović, Jelena Pucarević, Marko Radenković, Dejana Radišić Pešić, Dušan Radišić, Ana Radivojević, Radovan Radoman, Renata Radovanović, Vladimir Radulović, Nemanja Radusinović, Aleksandar Rajčić, Mirko Rakojević, Tatjana Rakojević, Ana Raković, Ivan Rašković, Grozdana Šišović, Dejan Milanović, Zorica Međo, Aleksandra Praštalo, Nikola Milanović, Aleksandar Ristić, Katarina Ristić, Aleksandar Ristović, Arber Sadiku, Gezim Sadiku, Ana Savić, Dubravka Sekulić, Slobodan Danko Selinkić, Sanja Simonović, Miloš Spasić, Branislav Spasojević, Maja Dragišić, Milan Božić, Marko Stojković, Milica Milosavljević, Dunja Ratković, Saša Lukić, Pavle Stamenović, Danica Stanković, Oliver Stanković, Branko Stanojević, Maja Stanojević, Dragan Stevanović, Nebojša Stevanović, Nikola Stevanović, Vladimir Stevanović, Vojislav Stevanović, Vladan Stevović, Stjepanović Nenad, Dušan Stojanović, Stefan Stojanović, Nikola Stojković, Marija Strajnić, Dijana Novaković, Maja Trbović, Aleksandra Nikitin, Dušan Nenadović, Oliver Stanković, Dragana Stevanović, Aleksandar Šavikin, Grozdana Šišović, Janko Tadić, Milan Tanić, Milica Tasić, Ana Savić, Alen Spahić, Dubravka Sekuli, Nataša Janković, Adrijan Karavdi, Ognjen Stanisavljević, Mihailo Timotijević, Dejan Todorović, Maja Trbović, Žarko Uzelac, Pavle Vasev, Ljiljana Vasilevska, Milica Vasiljević, Dragana Vasiljević Tomić, Miomir Vasov,Dejan Vasović, Vojislava Vasović, Milorad Vidojević, Bojana Vitorović, Goran Vojvodić, Mirosanda Vranić, Jelan Vučić, Aleksandru Vuja, Milan Vujović, Marko Vuković, Zlata Vuksanović Macura, Jelena Zagorac, Miona Zdravković, Snežana Zlatković, Nikola Žikić, Katarina Živković, Milan Živković, Miloš Živković, Stevan Žutić, Maroje Mrduljaš, Vladimir Kulić, Dejan Jović, Nika Grabar, Petra Čeferin, Robert Burghardt, Gal Kirn, Irena Šentevska, Dubravka Sekulić, Lana Lovrenčić, Ivan Kucina, Milica Topalović, Marko Sančanin, Divna Penčić, Biljana Spirikoska, Jasna Stefanovska, Ines Tolić, Nina Ugljen Ademović, Elša Turkušić, Matevž Čelik, Alenka Di Battistta, Ana Džokić I Marc Neelen, Nebojša Milikić, Tanja Damjanović Conley, Jelica Jovanović, Višnja Kukoč, Vesna Perković-Jović, Martina Malešič, Luciano Basauri, Dafne Berc, Dinko Peračić, Miranda Veljačić, Bogo Zupančić, Tamara Bjažić Klarin, Jelena Grbić, Dragana Petrović, Luka Skansi, Dražen Arbutina, Hela Vukadin, Ana Šilović, Simona Vidmar, Matevž Čelik Ako Vas nešto zanima, slobodno pošaljite poruku.

RIČARD POPKIN ISTORIJA SKEPTICIZMA OD SAVONAROLE DO BEJLA Prevod - Predrag Milidrag Izdavač - Fedon, Beograd Godina - 2010 672 strana 24 cm Edicija - Daimon ISBN - 978-86-86525-29-1 Povez - Tvrd Stanje - Kao na slici, tekst bez podvlačenja SADRŽAJ: Predgovor Reči zahvalnosti Uvod 1. Intelektualna kriza reformacije 2. Oživljavanje grčkog skepticizma u šesnaestom veku 3. Mišel de Montenj i nouveaux pyrrhoniens 4. Uticaj novog pironizma 5. Libertins érudits 6. Protivnapad počinje 7. Konstruktivni ili umereni skepticizam 8. Herbert od Čerberija i Žan de Šijon 9. Dekart: Pokoritelj skepticizma 10. Dekart: Skeptique malgré lui 11. Neki duhovni i religijski odgovori na skepticizam i Dekarta - Henri Mor, Blez Paskal i kvijetisti 12. Politički i praktički odgovori na skepticizam - Tomas Hobs 13. Filozofi Kraljevskog društva - Vilkins, Bojl i Glenvil 14. Biblijska kritika i početak religijskog skepticizma 15. Spinozin skepticizam i antiskepticizam 16. Skepticizam i metafizika skraja sedamnaestog veka 17. Novi skeptici - Simon Fuše i Pjer-Danijel lj 18. Pjer Bejl - Superskepticizam i počeci prosvetiteljskog dogmatizma Literatura Objavljeni materijal Rukopisni materijal Dodaci I. Skeptično o Istoriji skepticizma Da li je bilo,,pironističke krize` u ranoj modernoj filozofiji? Kritička beleška o Ričardu H. Popkinu Literatura II. Čovek i filozofija Ričard Popkin - jedna lična zabeleška PREDRAG MILIDRAG - Eros vedrine Indeks `Ričard Popkin jedan je od najuticajnijih savremenih tumača skepticizma, a njegova knjiga prati istoriju skepticizma od Savonarole do Bejla (od 1450. do 1710. godine). Taj period nije izabran slučajno. U tih bezmalo 300 godina najpre je iznova otkriven grčki skepticizam, potom inkorporiran u iskustvo renesanse, zatim izložen novim tumačenjima i preobražajima, da bi i sam odigrao nezaobilaznu ulogu kod velikih filozofa poput Dekarta, Paskala, Spinoze, Hobsa, ili iznova propitan u teološkim raspravama tog perioda. Popkin pripada američkoj školi istoričara filozofije, što podrazumeva besprekorno poznavanje teme o kojoj piše, strogost u izlaganju i, uprkos tome što je reč o tekstu koji se prostire na gotovo 700 stranica, ekonomičnost izraza. Već u prvoj rečenici knjige Popkin precizira da je skepticizam filozofsko gledište a ne niz sumnji koji se vezuje za tradicionalna religijska verovanja, što znači da je ključni ulog svake skeptičke pozicije – istina. Ipak, Popkin ne suprotstavlja skepticizam i fideizam, skeptika i vernika, kako bi se moglo očekivati s obzirom na suprotstavljenost te dve pozicije. Nikada skepticizam, sugeriše autor, nije puko neverovanje, niti je fideizam slepo verovanje. Iako skeptik preporučuje suzdržavanje od suđenja koje počiva na verovanju, to ne znači da je verovanje irelevantno za ono do čega je skeptiku stalo – do nesumnjive istine. Upotrebljavajući pojam fideizma onako kako ga je oblikovala literatura na engleskom jeziku, Popkin, zapravo, nastoji da jasnije istakne skeptički element koji je, tvrdi on, uključen u fideističko gledište. Popkinov tekst nezaobilazan je u svakoj raspravi koja sumnju koristi kao način da se dođe do delotvorne istine.` Ako Vas nešto zanima, slobodno pošaljite poruku. Richard H. Popkin The History of Scepticism Agripa Od Neteshajma Hajnrih Kornelije Agrippa Von Nettesheim Henricus Cornelius Aristotel Aristotle Arkesilaj Iz Pitane Antoan Arno Antoine Arnauld Sveti Avgustin Augustine Fransis Bejkon Francis Bacon Pjer Bejl Pierre Bayle Džordž Berkli George Berkeley Tomas Bernet Thomas Burnett Anri Bison Henri Busson Robert Bojl Boyle Hari Breken Harry Bracken Gi De Brije Guy De Brues Đordano Bruno Giordano Pjer Burden Pierre Bourdin Ciceron Vilijam Čilingvort William Chillingworth Žilijen Ejmar D`anžer Julien Eymard D`angers Gabrijel Danijel Gabriel Daniel Rene Descartes Pjer Demezo Pierre Desmaizeaux Žak Di Bosk Jacques Du Bosc Eli Diodati Elie Diogen Laertije Žak Davi Diperon Jacques Davy Duperron Žan Diveržije De Oran Džon Djuri John Dury Johan Ek Johann Eck Erazmo Roterdamski Anri Etjen Henri Estienne Samjuel Fišer Samuel Fisher Lučano Floridi Luciano Saleški Franja Simon Fuše Foucher Galileo Galilej Galilei Fransoa Garas Francois Garasse Euđenio Garin Eugenio Pjer Gasendi Pierre Gassendi Džozef Glenvil Joseph Glanvill Žan Gonteri Jean Gonery Tulio Gregori Tullio Gregory Hugo Grocijus Grotius Anri Guije Henri Gouhier Mari De Gurne Marie Gournay Herbert Od Čerberija Herbert Cherbury Gentijan Hervet Gentianus Hervetus Dejvid Hjum David Hume Tomas Hobs Thomas Hobbes Abraham Ibn Ezra Pjer Danijel Ije Pierre Daniel Huet Menaše Ben Izrael Menasseh Israel Ralf Kadvort Ralph Cudworth Žan Kalvin Jean Calvin Žan Pjer Kami Jean Pierre Camus Tomazo Kampanela Tommaso Campanella Imanuel Kant Karnead Sebastijan Kastelio Seren Kjerkegor Soren Kierkegaard Kristofer Klavijus Christopher Clavius Aleksandar Koare Alexandre Koyre Luj Burbon De Konde Nikola Kopernik Nicolaus Copernicus Pol Oskar Kristeler Entoni Ešli Kuper Anthony Ashley Cooper Fransoa La Mot Le Aje Francois La Mothe Le Vayer Isak La Pejrer Isaac La Peyrere Elizabet Labrus Elisabeth Labrousse Gotrfird Vilhelm Fon Lajbnic Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Pjer Le Loajepierre Le Loyer Žan Leklerk Jean Le Clerc Rober Lenobl Lenoble Elejn Limbrik Džon Lok John Locke Luj Martin Luter Luther Hose Maja Neto Jose Maia Može Majmonid Moses Maimonides Nikola Malbranš Nicolas Malebranche Leonar De Marande Karl Marks Marx Žil Mazaren Jules Kozimo Di Mediči Cosimo Maren Mersen Marin Mersenne Džozef Mid Joseph Mede Migel De Molinos Miguel Mošel De Montenj Michel Montaigne Henri Mor Henry More Silvija Mur Sylvia Murr Đovani Nezi Giovanni Nesi Gabrijel Node Gabriel Naude Isak Njutn Isaac Newton Ezekijel Olaso Ezequiel Džon Oven John Owen Đani Paganini Gianni Paracelzus Blez Paskal Blaise Pascal Gi Paten Guy Patin Sveti Pavle Kristof Pfaf Christophe Pfaff Piko Dela Mirandola Đanfrančesko Pico Della Gianfracesco Giovanni Rene Pintar Pintard Piron Platon Plutarh Henrik Regijus Henry Regius Džon Herman Rendal Arman Žan Di Plesis Rišelje Jean Du Plessis Duc Richelieu Francisko Sančez Francisco Sanchez Đirolamo Savonarola Girolamo Rajmund Sebond Raimond Sekst Empirik Sextus Empiricus Sen Siran Saint Cyran Migel Servet Miguel Servetus Martin Shokus Martinus Schoockius Rišar Simon Richard Simon Sokrat Samuel Sorbjer Sorbiere Šarl Sorel Baruh Spinoza Leo Straus Fortunat Strovski Strowski Pjer Šaron Pierre Charron Žan De Šijon Jean Silhon Čarls Šmit Charles Schmitt Džon Tilotson John Tillotson Fransoa Veron Francois Đorđo Antonio Vespuči Giorgio Vespucci Pjer Vile Pierre Villey Džon Vilkins John Wilkins Gizbert Voetije Volter Džon Votkins John Watkins Ričard Votson Richard Watson Zenon Iz Eleje Isak Žaklo Isaac Jaquelot Etjen Žilson Etienne Gilson Pjer Žirje Pierre Jurieu

G. K. Česterton - Četvrtak 1920. - retko (Gilbert Keith Chesterton - Čovek koji je bio Četvrtak) Sarajevo, Hrvatska tiskara D.D., 1920., 177 str., mek povez, 19.5x12.5cm antikvarni kolekcionarski primerak `Čovek koji je bio četvrtak: Noćna mora` prvi put je objavljen 1908. i često nazivan `metafizičkim trilerom`. London iz viktorijanskog doba, Gabriel Syme regrutovan je u Scotland Jardu u tajni anti-anarhistički policijski korpus. Lucian Gregori, anarhistički pesnik, živi u predgrađu parka Šafran. Syme ga upoznaje na zabavi i raspravljaju o značenju poezije. Gregori tvrdi da je pobuna osnova poezije. Syme se buni, insistirajući da suština poezije nije revolucija, već zakon. Antagonira Gregorija tvrdeći da je najpoetičnije od čovekovih kreacija red vožnje za Londonsko podzemlje. Sugeriše da Gregori zapravo nije ozbiljan u vezi sa anarhizmom, što toliko iritira Gregorija da odvodi Simea na podzemno mesto anarhista, pod zakletvom da nikome ne otkriva njegovo postojanje. Centralno veće se sastoji od sedam muškaraca, od kojih svaki koristi naziv dana u nedelji kao pseudonim. ... Česterton je bio engleski književnik, a njegov bogat i raznolik stvaralački opus uključuje novinarstvo, poeziju, religiozna dela, biografiju, fantaziju i detektivsku fikciju. Bio je omiljeni Borhesov pisac, i uticao na rad Erika Artura Blera (koga znamo po imenu Džordž Orvel). ---- Gilbert Keith Chesterton (Campden Hill, 29. svibnja 1874. – London, 14. lipnja 1936.), engleski književnik, pjesnik, romanopisac, esejist, pisac kratkih priča, filozof, kolumnist, dramatičar, novinar, govornik, književni i likovni kritičar, biograf i kršćanski apologet, književnik katoličke obnove. Chestertona su nazivali `princem paradoksa` i `apostolom zdravog razuma`. Jedan je od rijetkih kršćanskih mislilaca kojemu se podjednako dive liberalni i konzervativni kršćani, a i mnogi nekršćani. Chestertonovi vlastiti teološki i politički stavovi bili su prerafinirani da bi se mogli jednostavno ocijeniti `liberalnima` ili `konzervativnima`. Za paradoks je govorio da je istina okrenuta naglavačke, da bi tako bolje privukla pozornost. Osnovano je smatrati da pripada uskome krugu najvećih književnika 20. stoljeća. 1935. je bio nominiran za Nobelovu nagradu za književnost, ali upravo te godine jedini put u povijesti dotična nije dodijeljena ta nagrada za književnost, ne računajući godine svjetskih ratova. Ne zna se sa sigurnošću razloge, ali zacijelo nije dodijeljena da je ne bi dobio veliki i djelotvorni kršćanski pisac Chesterton. Mnoge su pape cijenili Chestertona, među kojima Benedikt XVI., još dok nije bio papa, često ga je citirao, a papa Franjo još dok je bio nadbiskup Buenos Airesa, dao je Jorge Mario Bergoglio svoj blagoslov na molitvu za proglašenje Chestertona blaženim. Jedan od najvećih tomista 20. stoljeća Étienne Gilson za Chestertonovo Pravovjerje kaže da je `najbolje apologetsko djel dvadesetoga stoljeća`. Institut za vjeru i kulturu Sveučilišta Seton Hall u New Jerseyu nosi njegovo ime te izdaje znanstveni časopis The Chesterton Review. Chesterton je rođen u Campden Hillu, Kensington, London, kao sin Marie Louise (Grosjean) i Edwarda Chestertona. U dobi od jednog mjeseca bio je kršten u Crkvi Engleske. Chesterton se prema vlastitim priznanjima kao mladić zainteresirao za okultno, a sa svojim bratom Cecilom eksperimantirao je sa zvanjem duhova. Chesterton se obrazovao u Školi `St. Paul`. Pohađao je školu umjetnosti kako bi postao ilustrator, a pohađao je i satove književnosti na Londonskom sveučilišnom kolegiju, no nije završio nijedan fakultet. Chesterton se oženio za Frances Blogg 1901., i sa njom ostao do kraja svog života. Sazrijevanjem Chesterton postaje sve više ortodoksan u svojim kršćanskim uvjerenjima, kulminirajući preobraćanjem na Katoličanstvo 1922. godine. Godine 1896. počeo je raditi za londonske izdavače `Redwaya`, i `T. Fisher Unwina`, gdje je ostao sve do 1902. Tijekom ovog perioda započeo je i svoja prva honorarna djela kao novinar i književni kritičar. `Daily News` dodijelio mu je tjednu kolumnu 1902., zatim 1905. dobiva tjednu kolumnu u `The Illustrated London News`, koju će pisati narednih trideset godina. Chesterton je pokazao i veliko zanimanje i talent za umjetnost. Chesterton je obožavao debate i često se u njih upuštao sa prijateljima kao što su George Bernard Shaw, Herbert George Wells, Bertrand Russell i Clarence Darrow. Prema njegovoj autobiografiji, on i Shaw igrali su kauboje u nijemom filmu koji nikada nije izdan. Godine 1931., BBC je pozvao Chestertona na niz radijskih razgovora. Od 1932. do svoje smrti, Chesterton je isporučio više od 40 razgovora godišnje. bilo mu je dopušteno, a i bio je potican, da improvizira kod svojih obraćanja.

STEPHEN FARTHING UMJETNOST VODIČ KROZ POVIJEST I DJELA Predgovor - Richard Cork Prevod - Dunja Kalođera, Petra Kljaić, Vedran Pavlić, Maja Rožman Izdavač - Školska knjiga, Zagreb Godina - 2015 576 strana 25 cm ISBN - 978-953-0-61769-8 Povez - Broširan Stanje - Kao na slici, tekst bez podvlačenja SADRŽAJ: Predgovor Uvod 1 Od pretpovijesti do 15. stoljeća 2 15. 116. stoljeće 3 17.i 18. stoljeće 4 19. stoljeće 5 Od 1900. do 1945. 6 Od 1946. do danas Pojmovnik Suradnici Izvori citata Kazalo Popis nositelja autorskih prava objavljenih slika Zahvale `Najpristupačnija povijest svjetske umjetnosti ikad objavljena. Više od 1100 ilustracija u boji najpoznatijih umjetničkih djela. Obuhvaća sve umjetničke forme, od slikarstva i kiparstva do konceptualne umjetnosti, od prapovijesti do naših dana. Umjetnost – vodič kroz povijest i djela započinje sveobuhvatnim povijesnim pregledom koji umjetnost smješta u kontekst društvenih i kulturnih zbivanja od razdoblja prije nastanka prvih država. Knjiga je organizirana kronološki te prati evoluciju umjetničkih razdoblja i pokreta. Bogato ilustrirani stručni tekst pokriva sve umjetničke forme, od slikarstva i kiparstva do konceptualne i izvedbenih umjetnosti. Temeljito vrednovanje ideja i radova ključnih umjetnika otkriva kako su pojedini umjetnici utjecali na rad drugih te što su pokušavali ostvariti svojim djelima. Detaljni kronološki sažetci kulturnih strujanja i života pojedinih umjetnika objašnjavaju povijesni kontekst. Posebno su obrađena i detaljno analizirana remek-djela koja u sebi utjelovljuju ključne značajke svakog pojedinog razdoblja i pokreta. Objašnjeno je sve, od korištenja boja i vizualnih metafora do tehničkih inovacija i trajnog nasljeđa pojedinog djela, što vam omogućuje da kao nikad dosad spoznate puno značenje svjetski poznatih remek-djela. Uživajte u složenim detaljima mogulskih minijatura, doznajte sve o važnosti japanskih grafika iz devetnaestog stoljeća, upoznajte se sa znanstvenim temeljima teorija boja koje su utjecale na Seuratovo zapanjujuće Nedjeljno poslijepodne na otoku La Grande Jatte, te otkrijte zašto su Picassove Gospođice iz Avignona u svoje vrijeme izazvale pravi skandal. Stephen Farthing slikar je i profesor crtanja na Umjetničkom sveučilištu u Londonu. Godine 1990. izabran je za dekana Visoke likovne škole Ruskin Sveučilišta Oxford, a 1998. godine postaje član Kraljevske umjetničke akademije u Londonu. Magistrirao je slikarstvo na Kraljevskom umjetničkom koledžu u Londonu, a likovne umjetnosti predaje od 1977. godine. Glavni je urednik knjige 1001 slika koju morate vidjeti prije smrti. Preveli s engleskoga Dunja Kalođera, Petra Kljaić, Vedran Pavlić, Maja Rožman.` Ako Vas nešto zanima, slobodno pošaljite poruku. This Is Art Stiven Farting Ričard Kork Umetnost Vodič Kroz Povest I Dela Istorija Umetnosti Apstraktni Ekspresionizam Vito Acconci Ansel Adams Afrička Umetnost Antička Umetnost Arte Povera Art Nouveau Francis Bacon Barok Georg Baselitz Bauhaus Abrey Beardsley Giovanni Bellini Joseph Beuys Hieronymus Bosch Derek Boshier Sandro Botticelli Constantin Brancusi Georges Braque Pieter Stariji Bruegel Michelangelo Buonarroti Vizantijska Umetnost Giovanni Antonio Canal Giovanni Antonio Canaletto Michelangelo Merisi Caravaggio Giorgio Barbarelli Castelfranco Paul Cezane Marc Chagall Giorgio De Chirico Gustav Courbet Dada Salvador Dali Jacques Louis David Edgar Degas Eugenedelacroix Robert Delaunay De Stijl Digitalna Umetnost Theo Von Dooesburg Marcel Duchamp Albrecht Durer Egipatska Umetnost Tracey Emin Jacob Epstein Max Ernst Ekspresionizam Jan Van Eyck Fovizam Fotografija Jean Honore Fragonard Piero Della Francesca Lucian Freud Futurizam Paul Gauguin Theodore Gericault Jean Leon Gerome Alberto Giacometti Hugo Van Der Goes Vincet Van Gogh Gotika Francisco De Goya Grčka Umetnost Juan Gris Raoul Hausmann Hiperalizam David Hockney Katsushika Hokusai William Holman Hunt Edward Hopper Impresionizam Indijska Umetnost Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres Islamska Umetnost Japanska Umetnost Frida Kahlo Vasilij Kandinski Kineska Umetnost Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Paul Klee Yves Klein Gustav Klimt Konceptualna Umetnost Kubizam Land Art Fernand Leger Sol Lewitt Roy Lichtenstein Rene Magritte Kasimir Malevich Edouard Manet Manirizam Franz Marc Henri Matisse Meksička Umetnost John Everett Millais Minimalizam Modernizam Amadeo Modigliani Piet Mondrian Claude Monet Albert Moore Robert Motherwell Takashi Murakami Neoklasicizam Neoekspresionizam Barnett Newman Emil Nolde Op Art Orijentalizam Jose Orozco Denis Peterson Pablo Picassocamille Pissarro Jackson Pollock Jacopo Carucci Pontormo Pop Art Postimpresionizam Primitivizam Realizam Regionalizam Pierre Restany Pierre Auguste Renoir Rembrand Harmensz Rijn Diego Rivera Rokoko Aleksandar Rodčenko Rimska Umetnost Romanika Romantizam Dante Gabriel Rossetti Mark Rothko Henri Rousseau Peer Paul Rubenskarl Schmidt Rotluff Secesija Georges Pierre Seurat Paul Signac David Siquerios Suprematizam Nadrealizam Simbolizam Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula Urbana Umetnost Diego Velazquez Leonardo Da Vinci Jeff Wall Andy Warhol John William Waterhouse Jean Antonie Watteau Rogier Van Der Weyden James Mcneill Whisler Rachel Whiteread

U dobrom stanju The Saga of Hog Island: And Other Essays in Inconvenient History Paperback – January 1, 1977 by James J. Martin Publisher : Ralph Myles; First Edition (January 1, 1977) Language : English Paperback : 208 pages ISBN-10 : 0879260211 ISBN-13 : 978-0879260217 Item Weight : 11.2 ounces Martin`s additionist essays are historical correctives that have relevance to events today. The first essay tells the story of the massive world war 1 ship building yard built at Hog Island, now the site of Philadelphia International Airport. Legend has it that the `Hoagie` sandwich may have had it`s origin among the many Italian American shipyard workers. At it`s peak as many as 36,000 workers were employed on Hog Island yards. This vast facility was established to mass produce cargo ships for the WW1 war effort, along the lines of the more famous `Liberty Ships` of WW2. But the program was dogged by scandal and massive accounting `incompetence`. In the end Hog Island, owned and operated by a consortium who`s membership register reads like a `Who`s Who` of the American business and industrial elite, delivered 122 ships that cost of `at least` $235 million to build (that is $2.4 billion in 2007 dollars, ~$20M each). Most of the ships were ultimately sold for a mere $35,000 each ($353,000 in 2007 dollars). Hog Island itself was a part of a larger web of mismanagement that embraced the Shipping Board and the Emergency Fleet Corporation. `Alfred D. Lasker, who assumed the direction of the Shipping Board under President Harding, on July 16, 1921 decalred that the total government `loss` on the ship construction, operation and leasing activities during the World War came to $4,000, 000, 000- double the figure originally thought.` Corrected for inflation, those 1921 dollars amount to approximately $40.3 billion in 2007 dollar terms. In a January 31, 2005 CNN article published under the headline `Audit: U.S. lost track of $9 billion in Iraq funds`. `Nearly $9 billion of money spent on Iraqi reconstruction is unaccounted for because of inefficiencies and bad management, according to a watchdog report published Sunday.` It`s probably not being over dramatic to say that the vast `losses` in US military-industrial spending represent part of a 90 year tradition of apparently unending fiscal incompetence. On the 10th January 2000, `The Weekly Standard` declared that Winston Churchill was `Man of the Century`. In his second essay `The Consequences of World War Two to Great Britain: Twenty Years of Decline, 1939 -1959` provides a much needed tonic to Churchill worship, and his elevation to the status of prophet, as regularly recycled by the History Channel and George W Bush`s bedside reading. In 1942 Churchill declared `I have not become His Majesty`s first minister to preside over the dissolution of the British Empire.` Yet to a large extent that was his real legacy as Martin explains. Martin`s piece also illustrates the extraordinary fickleness of many American conservatives. Ever ready (and probably rightfully so) to condemn FDR for bending over too far to accomodate Josef Stalin, FDR`s `willing accomplice` Winston Churchill largely escapes scot free from conservative criticism. Yet less than a year before his famous 1946 Fulton Missouri `Iron Curtain` speech, Churchill was praising Comrade Joe in parliament. Perhaps had FDR, who died in April 1945, had lived another year he would have had time to perform a public somersault too. Martin provides an eye opening essay on Mussolini`s campaign against the mafia. Like most students of history I had heard of this but had assumed Mussolini must have conducted some kind of fascist purge or authoritarian `round up` of mafiosi. Not so. Mussolini`s campaign was quite civilised with the accused being provided legal rights and indeed many accused successfully defended themselves against the charges and walked free. Still despite these `handicaps`, Mussolini`s lawful and orderly campaign against the mobs was one of the largest and most successful campaigns against organised crime anywhere, and much of it`s gain was unravelled by a mixture of postwar chaos and some allied cooperation with the mafia. Martin explores this last angle too. Many of us have heard of Lucky Luciano`s claims to have helped protect the New York waterfront from German saboteurs and to have aided the allied advance across Sicily. These stories indeed have become legends of sort. Martin sees them as shameless self promotion from a crook on the make. The allied armoured and amphibious campaign in Sicily wasn`t dependent on local mafiosi to show them goat tracks behind the Axis lines. Martin has three essays on the Pacific War. Only one could really be called revisionist. In `Pearl Harbor: Antecedents, Background and Consequences` he outlines the background to Japanese-American rivalry in the Pacific in the decades and days before Pearl Harbor. Usually `the revisionist position` here (as if there were just one) is summarised as the claim that FDR engaged in a conspiracy over Pearl Harbor. The old mainstream belief that FDR was really an innocent victim of a surprise attack has now largely been dismissed from serious scholarship, thanks to decades worth of unpraised work by revisionist historians. The new mainstream belief is that the unheeded warnings of imminent attack were mishandled. Administrative incompetence rather then conspiracy provides a better explanation. The revised mainstream account arbitrarily assumes incompetence and conspiracy are mutually exclusive categories. More to the point was `Rainbow 5`, the then secret ABDA (Australian-British-Dutch-American) agreement `..to fight the Japanese in Asia if their forces crossed a geographic line..[which]..approximated the northerly extremity of the [Dutch East Indies].` The US government was advised that the Japanese had crossed the magic line on December 3 (Washington time) and that America`s allies naturally expected the US government to live up to it`s agreements. The apparent mishandling of reports concerning Japanese fleet movements in the northern pacific need to be considered with the ABDA timeline in mind. Considering the great difficulty the administration had in having conscription passed in Congress, it squeaked through by just one vote, a certain degree of planned incompetence, an art form familiar to anyone who has worked in a bureaucracy can attest to, is not an unreasonable explanation (although one inherently and deliberately hard to prove). Nor is such a hypothesis equivalent to Roswell UFOs or the Bavarian Illuminati as anti-conspiracists like to maintain. Martin also essays the stories of Colin Kelly and `Tokyo Rose`. Kelly was an airman who died early in the Philippines campaign after his aircraft was hit following an indecisive attack on a second or third tier Japanese vessel, probably a supply transport. In the dark days of continuous bad news from the Pacific his deeds were inflated to legendary status by the media, and indeed the administration, until it sounded as if he single handedly sank a battleship in a one-man kamikaze attack. Subsequent revisions of the official account deflated the Kelly story down to a footnote before disappearing in later versions. The whole story seems to echo in the 2003 Jessica Lynch story. Times indeed have changed, the spin cycle is faster these days. The `Tokyo Rose` essay details how a soldiers` myth, that there was one seductive Japanese propaganda broadcaster luring GIs with tales of unfaithful girlfriends back home, led to a miscarriage of justice that scarred the life of Iva Toguri, a young Japanese American woman accidentally caught up in Japan whilst visiting family in the days surrounding Pearl Harbor. Toguri, one of many english language broadcasters was made carry the can for the lot. With the boom in recent years of feminist and multicultural studies, all under the history banner, it is surprising that Martin`s `The Framing of Tokyo Rose`, especially with it`s hints of sexuality, hasn`t become a standard in gender studies. This too has modern references, and not just in the United States. The current `War on Terror` is leaving in it`s wake a growing `bodycount` of innocent bystanders caught at the wrong place, often to become the victims of tragic miscarriages of justice as government security apparatus strikes out at it`s elusive quarry. The book is rounded off with three brief appendix essays, essentially magazine articles. The first compares the blacklists imposed on Axis commerce in South America by the US in the years before Pearl Harbor to the attempted Arab boycott of jewish owned firms in the US in 1975. The second discusses the Morgenthau Plan and the third is a brief history of political assassination in the first half of the 20th century. The last article is definitely the best, the Morgenthau Plan article is not comprehensive and seems to have been prematurely ended, neglecting to cover it`s demise and the boycott article seems to me to be `drawing a long bow`. The Rockefeller administered Axis boycott in South America, whatever else it was, was part of an actual economic warfare plan, the Arab boycott barely deserved the name and was almost entirely a propaganda campaign lacking serious enforcement teeth. If anything it probably boomeranged and hardened international opinion against the Arab campaign. `The Saga of Hog Island` is recommended to anyone interested in modern history.

LYNN HAROLD HOUGH THE MEANING OF HUMAN EXPERIENCE Izdavač - Abingdon-Cokesbury Press, New York Godina - 1945 368 strana 24 cm Povez - Tvrd Stanje - Kao na slici, tekst bez podvlačenja SADRŽAJ: BASIC CONSIDERATIONS Chapter I: CONFRONTING THE HUMAN 1. The Men We Can Scarcely See. 2. The Men of the River Valleys. 3. The Men of Masterful Mind. 4. The Man Who Controls Other Men. 5. The Everlasting Barbarian. 6. The Men of Slippery Mind. 7. The Men Who Made Words Slaves. 8. The Men Who Enshrined Memories. 9. The Men Who Captured Dreams. 10. The Men Who Were Disturbed by the Moral Voice. 11. The Men Who Made Nations. 12. The Men Who Made Republics. 13. The Men Who Made Machines. 14. The Men Who Became Machines. 15. The Interpreters of the Battle of Impulses and Ideas. 16. The Alluring and Betraying Utopias. 17. The Men Who Have Seen Individuals Sharply. 18. The Man Everyman Sees. Chapter II: KNOWING AND THINKING. 1. The Necessary Assumptions. 2. The Possibility of Universal Skepticism. 3. The Mistakes of the Thinkers. 4. Freedom. 5. The Great Correlation: Thinker, Thought, Thing. 6. What the Mind Brings to Experience. Chapter III: THE NATURE OF THE REAL. 1. Materialism. 2. Realism. 3. Idealism. 4. Impersonal Realism. 5. Impersonal Idealism. 6. Personal Realism. 7. Personal Idealism. Chapter IV: THE ULTIMATE PERSON 1. The Ground of a Community of Personal Experience. 2. The Ground of the Existence of Persons. 3. Explaining the Personal by Means of the Impersonal. 4. Explaining the Impersonal by Means of the Personal. 5. Human Personality. 6. Divine Personality. 7. The Security of Experience in the Ultimate Person. 8. Moving Back to the Major Premise from the World of Experience. 9. Moving from the Ultimate Person Back to History. Chapter V: THE SPEECH OF THE GREAT PERSON. 1. The Speech of the Creator. 2. God`s Speech in Man. 3. God`s Speech in Nature. 4. `Natural Theology.` 5. Has God Spoken in the Ethnic Religions? 6. Classification of Religions. 7. The Ethnic Religions and `Natural Theology.` 8. The Ethnic Religions and Revelation. 9. Is There a Higher Revelation? THE HEBREW-CHRISTIAN WITNESS Chapter VI: THE RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE OF ISRAEL. 1. The Adventure of Man with Nature. 2. The Adventure of Man with Man. 3. The Adventure of Man with God. 4. The Unique Adventure in Palestine. 5. The God with a Character. 6. Borrowing and Transform- ing. 7. Things Left Behind. 8. Truths Apart from Experience. 9. Truth in Experience. 10. The Striking Individuals. 11. The Dedicated People. Chapter VII: THE HEBREW PROPHETS. 1. Elijah and Elisha. 2. Amos. 3. Hosea. 4. Isaiah. 5. Micah. 6. Jeremiah. 7. Nahum. 8. The Isaiah of the Exile. 9. Ezekiel. 10. God Meets Men at the Central Place of Their Own Experience. Chapter VIII: `THE REIGN OF LAW`. 1. Old Testament Laws. 2. Law as Convention. 3. Law as Ritual. 4. Natural Law. 5. Law as the Correlation of Human Sanctions. 6. Law as the Correlation of Divine Sanctions. 7. The Law in the Heart. Chapter IX: THE BATTLE WITH DOUBT AND THE LYRICAL VOICES 1. Habakkuk. 2. Job. 3. The Hero of the Book of Psalms. 4. The Indi- vidual Experiences of the Book of Psalms. 5. The Humanism of the Psalms. 6. The Evangelical Note in the Psalms. 7. The Law Is Taught to Sing. 8. Social Insights of the Psalms. 9. The Tragedies of the Book of Psalms. 10. The Triumphant Joy of the Psalms. 11. The Hallelujah Chorus. Chapter X: SERMONS ON HISTORY. 1. Samuel. 2. Saul. 3. David. 4. Solomon. 5. The Choice of Rehoboam. 6. Hezekiah. 7. Josiah. 8. The Living Forces in History. 9. The Divine Meanings in History. Chapter XI: THE STORY OF A BRIDGE 1. The Exile. 2. The Return from Exile. 3. The Resurrection of the Nation. 4. Persia. 5. Babylon. 6. Alexandria. 7. The Decadent Greeks. 8. The Great Patriots. 9. Rome. 10. The Fresh Insights. 11. Casually Accepted Beliefs. 12. The New Imperial World. Chapter XII: THE HUMAN LIFE DIVINE 1. The Portrait of Christ in the Gospels. 2. Vital Perfection. 3. The Compelling Person. 4. The Words. 5. The Great Insights. 6. The Deeds and the Life. 7. The Great Invitation and the Great Divide. 8. The Personal Experience Back of the Gospels. 9. The Criticism of Christian Experience. 10. The Human Life Divine. Chapter XIII: RELIGION AS REDEMPTION 1. Ideas Connected with Religion as Redemption. 2. The Classical Form of Christian Experience. 3. Some Historical Examples. 4. The Reverse Approach to Paul Through Twenty Centuries of Christian Experience. 5. The Pauline Theology and Classical Christianity. 6. `Other Sheep.` 7. Great Christians Who Were Not Evangelicals. 8. The Soft Substitutes. 9. The Modern Experience of Redemption. Chapter XIV: RELIGION AS APOCALYPSE 1. The Conditions of the Rise of Apocalyptic Literature. 2. Sense of Complete Frustration in the Presence of Evil Powers. 3. The Faith of the Hopeless Minority. 4. The Appeal from the Acts of Men to the Acts of God. 5. Mysterious Symbolisms Whose Central Message Is Obvious to the Oppressed. 6. Apocalyptic Writing as a Literature of Consolation. 7. Apocalyptic Writing as a Literature of Triumphant Hope. 8. Apocalypse as a Philosophy of History. 9. Modern European Theology and the Apocalyptic Mood. 10. The Permanent Significance of the Apocalyptic Elements in the Christian Religion. Chapter XV: THE QUEEN OF THE SCIENCES 1. Science as Measurement. 2. The Larger Conception of Science. 3. Theology, the Keystone of the Arch. 4. Exegetical Theology. 5. Biblical Theology. 6. Philosophical Theology. 7. The Greek Theology. 8. The Latin Theology. 9. The Intellect and the Will. 10. The Reformation Takes Theological Forms. 11. The Theology of Fulfillment. 12. The Theology of Crisis. 13. The Theology of Social Action. 14. The Great Synthesis. THE HUMANISTIC TRADITION Chapter XVI: THY SONS, O GREECE. 1. The Living Process. 2. The Mingling of Primitive and Civilized Life. 3. The Direct Gaze at Nature. 4. The Direct Gaze at Man. 5. The Dangerous Gift of Abstraction: the Good, the Beautiful, and the True. 6. The Living Faith in the Ideal. 7. The Halfway Houses: the Things Which Seem Better than Gods; the Virtues Which Have Fruits Without Roots. 8. The Deliverance from Abstraction. 9. Athens and Jerusalem. Chapter XVII: CRITICS OF MANY LANDS 1. The Voice of the Critic. 2. Through the Eyes of Aristotle. 3. Longinus and the Great Soul. 4. Cicero and the Battle Between Appetite and Reason. 5. Quintilian Directs the Man with a Voice. 6. Lucian Scorns His World. 7. Boethius Confronts Tragedy. 8. Thomas Aquinas Finds Reason in Theology. 9. Pico della Mirandola Finds the Dignity of Man. 10. Francis Bacon Turns to Nature and Misunderstands Human Values. 11. Dryden Comes to His Throne. 12. France Attains a Fine Certainty. 13. The Coffee House Becomes Articulate. 14. Dean Swift Castigates. 15. Dr. Johnson Pontificates. 16. Burke Beholds Sublimity. 17. Sainte-Beuve Writes Royally. 18. Carlyle`s Clouds and Darkness and Flashing Light. 19. Matthew Arnold Remembers the Best That Has Been Thought and Said in the World. 20. Ruskin Teaches Beauty to Face Social Responsibility. 21. Saintsbury, the Hedonist. 22. Physics and Biology Rampant. 23. The Freudians Inspire Literary Criticism. 24. The Social Radicals Have Their Day in Court. 25. Humanism Becomes Mighty in Irving Babbitt. 26. Humanism Becomes Christian in Paul Elmer More. 27, Evangelical Humanism Chapter XVIII: FICTION FINDS TRUTH AND FALSEHOOD 1. Escape. 2. Adventure. 3. Vicarious Satisfaction. 4. By the Light of a Thousand Campfires. 5. By the Lamps of a Thousand Libraries. 6. By the Fireplaces of a Thousand Homes. 7. The Isolated Reader Who Finds a Society in Books. 8. Fiction Heightens and Dramatizes Life. 9. Fiction Photographs Human Life. 10. Fiction Brings Back Golden Memories. 11. Fiction Brings Back Memories That Corrode and Burn. 12. Fiction Criticizes Life. 13. Fiction Records the Adventures of the Soul. 14. Fiction as the Voice of the Body. 15. Fiction Gives Life to Great Hopes. 16. Fiction Interprets Life. 17. Fiction and the Rights of the Soul Chapter XIX: POETRY OPENS AND CLOSES ITS EYES 1. Homer. 2. The Greek Tragedians. 3. Vergil. 4. Dante. 5. Chaucer. 6. Spenser. 7. Shakespeare. 8. Marlowe. 9. O Rare Ben Jonson. 10. John Donne. 11. Other Metaphysical Poets. 12. Alexander Pope. 13. John Keats. 14. Shelley. 15. Lord Byron. 16. Wordsworth. 17. Browning. 18. Tennyson. 19. Goethe. 20. Longfellow. 21. Lowell. 22. Whitman. 23. Hardy. 24. D. H. Lawrence. 25. Robert Bridges. 26. Edwin Arlington Robinson. 27. T. S. Eliot. 28. Robert Frost. 29. Decadent Poetry. 30. Finding One`s Way. Chapter XX: BIOGRAPHY HIDES AND TELLS ITS SECRETS 1. How Much Can We Know About Particular People? 2. How Much Can Particular People Know About Themselves? 3. Can We Know a Man`s Secret? 4. Through the Civilized Eyes of Plutarch. 5. Through the Spacious Eyes of Macaulay. 6. The Sensitive Plate of Sainte-Beuve. 7. The Biographical Detective Appears in Gamaliel Bradford. 8. The Perceptive Analysis of Gilbert Chesterton. 9. The Heroes. 10. The Saints. 11. The Statesmen. 12. The Thinkers. 13. The Scientists. 14. The Preachers. 15. The Reformers. 16. The Women. 17. The Men. 18. The Valley of Decision Chapter XXI: HISTORY AND THE CHRISTIAN SANCTIONS 1. The Breakdown of the Older States. 2. The Debacle in Greece. 3. The Debacle in Rome. 4. The Debacle in the Middle Ages. 5. The Debacle in the Renaissance. 6. The Debacle in the Reformation. 7. The Debacle in the Enlightenment. 8. The Debacle of the French Revolution. 9. The Debacle in the Society of Science. 10. The Debacle of the Society of Social Blueprints. 11. The Debacle in the Society of the Machine Age. 12. The Debacle of the Great Reversion. 13. Democracy Faces Fate. 14. The Judgment of the Christian Sanctions. THE EVANGELICAL SYNTHESIS Chapter XXII: ALL THE STREAMS FLOW TOGETHER. 1. Physical Well-Being. 2. Moral Well-Being. 3. Intellectual Well-Being. 4. Spiritual Well-Being. 5. Social Well-Being. 6. The Tragedy of Ignorance. 7. The Solution of the Problem of Ignorance. 8. The Tragedy of Incompleteness. 9. The Solution of the Problem of Incompleteness. 10. The Tragedy of Sin. 11. The Solution of the Problem of Sin. 12. The Tragedy of Social Disintegration. 13. The Solution of the Problem of Social Disintegration. 14. The Religion of Revelation. 15. The Religion of the Incarnation. 16. The Religion of the Cross. 17. Christus Imperator. Chapter XXIII: THE TRAGEDY OF THE GREAT GREGARIOUSNESS 1. The All-Inclusiveness of Hinduism. 2. The Nest of Fallacies. 3. You Cannot Affirm a Thing Without Denying Its Opposite. 4. A Relative Insight Is Not an Insight. 5. A Relative Loyalty Is Not a Loyalty. 6. A Relative Truth Is Not a Truth. 7. The Ladder of Confusion. 8. The Great Gregariousness Becomes the Complete Blackout. 9. The Great Distinctions. 10. The Living Corpus of Dependable Truth. Chapter XXIV: THE TRANSFIGURATION OF ETHICS. 1. Codes and Practice. 2. The Man with Ethical Experience. 3. The Personal and the Impersonal. 4. The Great Dilemma. 5. The Solution of the Antinomian. 6. The Conventional Solution. 7. The Solution of Those Who Get Lost in Details. 8. The Solution of a Shrewd Prac- ticality. 9. The Solution of Despair. 10. The Solution of Faith. 11. The Searching Power Which Christianity Brings to Ethics. 12. The New Spirit Which Christianity Brings to Ethics. 13. The Lyrical Gladness Which Christianity Brings to Ethics. 14. Christianity and the Creative Ethical Life. Chapter XXV: BEYOND THESE VOICES. 1. The Creature Who Must Have Eternity. 2. The Claims of the Unful- filled. 3. The Claims of Those Who Cry Out Against the Injustices of Time. 4. Man Without Eternity. 5. Eternity Without Man. 6. The Faith Written in the Soul of Man. 7. The Men of Social Passion Who Fear the Belief in Immortality. 8. The Final Adjudication. 9. The Faithful God. Index Ako Vas nešto zanima, slobodno pošaljite poruku. Aristotle Matthew Arnold Athanasius Karl Barth Robert Browning Oscar Cargill Cicero Charles Dickens William Fairweather Charles Kingsley Martin Luther William Robertson Nicoll Plato Socrates