Pratite promene cene putem maila

- Da bi dobijali obaveštenja o promeni cene potrebno je da kliknete Prati oglas dugme koje se nalazi na dnu svakog oglasa i unesete Vašu mail adresu.

1-19 od 19 rezultata

Broj oglasa

Prikaz

1-19 od 19

1-19 od 19 rezultata

Prikaz

Prati pretragu "Čase"

Vi se opustite, Gogi će Vas obavestiti kad pronađe nove oglase za tražene ključne reči.

Gogi će vas obavestiti kada pronađe nove oglase.

Režim promene aktivan!

Upravo ste u režimu promene sačuvane pretrage za frazu .

Možete da promenite frazu ili filtere i sačuvate trenutno stanje

RUS44) OMOT JE MALO OŠTEĆEN. VELIKI FORMAT, 188 STRANA. Publishers Description: This book takes all the logos that were in Rockport Publishers best-seller, LogoLounge and collects them in one small, neat, pictorial handbook for easy reference.There are no lengthy case histories, just logos, logos, and more logos. Its a fast-paced book featuring one to six logos per page to allow designers to easily shop for ideas. Logos are among the most important elements a designer can create, so it is no surprise that they are always looking for new, fresh ideas. LogoLounge delivers just that. Its predecessor showcased the logos along with the stories of how they came to be; this compact version puts the spotlight on the logos alone, making it the perfect handbook to logo design.

Nina Holland - Inkle loom weaving Pitman publishing, London 1973. godine na 144. strane, bogato ilustrovano, u tvrdom povezu sa zastitnim omotom. Knjiga je odlicno ocuvana. Synopsis: Techniques. Building an inkle loom; Alternative loom plans; Making a shuttle; Shopping for yarn; Warping the loom : a three-color belt; Yarn texture : a choker; Pattern design: tied bodice belts; Color ideas : curtain ties; Dyeing your yarn : a tie-die belt; The Rya technique : decorative bell hangings; Color plates; Projects. Belts for different occasions; A guitar strap; Headbands; A man`s tie; An eyeglass case; A belt in leno lace; A campstool seat; Slip covers for a director`s chair; Handbags; Pin cushions and balsam bags; Border designs; lothing designs; Wall hangings; A room divider; A hanging that moves; Christmas tree swags; Weaving a wider fabric; Selling your weaving; Glossary; elected bibliography.

Izdavač: AMPHOTO, American Photographic Book Publishing Co., New York Povez: tvrd sa omotom Broj strana: 175 Ilustrovano. Vrlo dobro očuvana. This book gives you the latest comprehensive information on the Konica Autoreflex models T and A. It explains in clear and precise terms how to operate the Autoreflex, and how to get the best results from youe excellent Konica equipment. There are chapters devoted to lenses, accessories, flash, exposure, closeup and macro photography, as well as an extended section on composition, craftsmanship, and timing. C O N T E N T S : 1. Introduction to Konica Autoreflex 2. Features of the Konica Autoreflex T and A 3. Lenses for the Konica 4. Exposure Tricks and Treats 5. Flash with the Konica 6. Closeup Photography 7. Konica Accessories 8. Composition: The Way We See 9. Konica Case History Pictures (K-135)

U dobrom stanju Publisher: Random House Special Attributes: 1st Edition Binding: Hardcover Place of Publication: New York Language: English Year Printed: 1959 “Moss Hart`s Act One is not only the best book ever written about the American theater, but one of the great American autobiographies, by turns gripping, hilarious and searing.” ―Frank Rich “Reading Act One is like going to a wonderful dinner party and being seated next to a man who is more charming, more interesting, smarter, and funnier than you ever knew men were capable of being. Moss Hart is alive in these pages, and I am in love with him.” ―Ann Patchett, author of This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage and Bel Canto “Is Act One for you? Only if you know that theater is spelled theatre, cast albums are not soundtracks, and intermission is twice as fun as halftime. In that case, not only is Act One for you--it is immediate and required reading.” ―Tim Federle, author of Better Nate Than Ever and Five, Six, Seven, Nate! “Act One is legendary in the theater world for one simple reason: it speaks personally to those of us who have chosen a life on or around the stage.” ―James Lapine About the Author Born in New York City in 1904, Moss Hart began his career as a playwright in 1925 with The Hold-Up Man, yet achieved his first major success in the 1930 collaboration with George S. Kaufman, Once in a Lifetime. In addition to numerous Broadway productions, such as The Man Who Came to Dinner and You Can`t Take it With You, which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1938, Hart wrote screenplays for Gentleman`s Agreement and A Star is Born. Moss Hart also gained universal recognition for his award-winning direction of My Fair Lady in 1956.

Knjiga ne izgleda ovako izvitopereno uživo. Slobodan Marković PISMA PROFESORU PALAVIČINIJU DA KOSTI Libero Markoni Retko u ponudi Faksimil izdanje Slobodan Marković Libero Markoni Ilustrovano crtežima Izdavač Prosveta Požarevac Povez broš Format veliki faksimil Godina 1977 Слободан Марковић (Скопље, 26. октобар 1928 — Београд, 30. јануар 1990) био је српски песник. Познат је и под надимком „Либеро“ или „Либеро Маркони“. Слободан Марковић S.Kragujevic, Sl.Markovic,Libero Markoni, 1983.JPG Слободан Марковић 1983. године Лични подаци Датум рођења 26. октобар 1928. Место рођења Скопље, Краљевина СХС Датум смрти 30. јануар 1990. (61 год.) Место смрти Београд, СФР Југославија Биографија Уреди Рођен је 1928. у Скопљу где му је отац Димитрије био на служби као официр војске. Детињство је провео у Пећи и у Београду, где је матурирао у Другој београдској гимназији. 1943. је био заточен у логору у Смедеревској Паланци. Неке од његових књига песама су „Седам поноћних казивања кроз кључаоницу“, „Једном у граду ко зна ком“ (1980). Објавио је 62 књиге а још две су штампане после његове смрти: „Јужни булевар“ и „Запиши то, Либеро“ које је приредила његова супруга Ксенија Шукуљевић-Марковић. Бавио се и превођењем, био је новинар у „Борби“, сликар и боем. За књигу „Лука“ добио је 1975. Змајеву награду. Написао је сценарио за филм Боксери иду у рај. Умро је 30. јануара 1990. и сахрањен у Алеји заслужних грађана на Новом гробљу у Београду. У време хајке на Милоша Црњанског Марковић је објавио поему `Стражилово` (као уредник у недељнику `Наш весник`). По доласку Црњанског у Београд, живели су у истом крају и повремено се дружили. Либеро о себи Уреди Слободан Марковић је сâм написао увод у књигу изабране поезије `Једном у граду ко зна ком`, у којем се овако изјаснио: `Уметност је мој живот. Нисам се трудио да у свемиру нађем сличност са собом. Знам да сам уникат и да немам двојника. По свој прилици, нећу ни имати потребе да га ангажујем.`[1] Истицао је да је прошао путем од интернационалисте и космополите ка безграничном универзализму: `Регионалне кловнове надуване национализмом, жалим. Моја сестра заиста спава на Поларном Кругу у спаваћици од фокине коже. Ноге перем у Њујоршкој луци. У Азербејџану имам унука... У Истанбулу деду који носи црквицу на длану. Извор киселе воде у Царској Лаври Високим Дечанима, моја је клиника, и моје опоравилиште.`[1] Анегдоте о Либеру Уреди Момо Капор је у својим забелешкама `011 (100 недеља блокаде)` описао Либерово умеће у кафанској кошарци, односно игри званој `убацивање шибице у чашу`, где се чаша поставља на средину кафанског стола, подједнако удаљена од свих играча који покушавају да са ивице стола убаце кутију шибица у њу. `Покојни Либеро Маркони је жмурећи убацивао шибицу у чашу, био је апсолутни првак света у том спорту, којим се може бавити само припит играч. Тада се постиже права зен-концентрација; играч се поистовећује с кутијом шибице у лету и њеним циљем, звонцавим дном чаше. Када шибица падне на дно, педесет поена. Стотину поена добија онај коме се шибица задржи на ивици чаше. Онај ко изгуби, плаћа следећу туру...` Борислав Михајловић Михиз је у својој књизи `Аутобиографија - о другима` описао и бројна дружења са писцима и песницима. Проводио је сате без алкохола са `учењацима` Дејаном Медаковићем и Павлом Ивићем, али и време уз чашицу са `распојасанима` Слободаном Марковићем и Либеровим пријатељем, сликаром Славољубом Славом Богојевићем. Дешавало се да весело друштво целу ноћ проведе у кафани, и ујутру прелази преко лукова панчевачког моста. Са пуним поуздањем у истинитост старе мудрости да `пијанцима и деци анђели подмећу јастуке`, окуражени приличном количином алкохола, правили су Либеро, Слава и Михиз такве вратоломије од којих `нормалним` људима застаје дах. Милиционери, који би их скидали са лукова моста, били су забезекнути пред оним што виде, и на крај памети им није било да `озлоглашену тројку` казне. Либеро је своје доживљаје и осећања приликом пијанчења описао у књизи `Пијанци иду дијагонално`, а прелажење луковима панчевачког моста учинио је вечним, помињући га у некрологу свом рано преминулом пријатељу Слави Богојевићу.[2] Слободан Глумац Архивирано на сајту Wayback Machine (1. јул 2019), главни уредник листа Борба, новинар и преводилац, био је пратилац Слободана Марковића на путовању у Швајцарску. Либеро је у једном периоду сарађивао у том листу пишући запажене прилоге који су излазили суботом. Редакција листа је одлучила да предузме нешто у погледу Либеровог опијања, за које је сматрано да иде на уштрб угледа листа. У циљу преваспитања, песнику је омогућен плаћени боравак у швајцарском санаторијуму за лечење зависности од алкохола. Због потребе да се у швајцарском конзулату у Милану среде неки папири, Слободан Глумац је оставио свог имењака и колегу у једном кафанчету, знајући да овај нема новца. Наручио му је лимунаду, и безбрижно се запутио ка конзулату. Формалности су потрајале, и Глумац се тек после три сата вратио у кафанче. Тамо га је сачекао следећи призор: Препун астал флаша пића, разбарушени Либеро даје такт и запева прве стихове: `Тиии ме, Мииицо, нееее воолеш...`, а италијански конобари дигнути на шанк, као и присутни гости, отпевају: `Цисто сумлам, цисто сумлам`...[3] Позамашни цех је некако плаћен, а како - ни данас се са сигурношћу не зна. Дела Уреди Од великог броја објављених књига Либера Марконија, тридесет и две су збирке песама. Писао је и препеве, путописе, репортаже, краћу прозу, драме, сценарија, приређивао антологије... Слободан је посебно уживао у поезији Јесењина, а о томе сведоче његови препеви песама великог руског песника у књигама Ко је љубио тај не љуби више и Растаћемо се уз смешак нас двоје. Ево неких наслова Либерових књига поезије: После снегова Свирач у лишћу Морнар на коњу Пијанци иду дијагонално Седам поноћних казивања у кључаоницу Ведри утопљеник Три чокота стихова Црни цвет Икра Умиљати апостол Посетилац тамног чела Тамни банкет Уклета песникова ноћна књига Елеонора жена Килиманџаро Једном у граду ко зна ком (штампана поводом 50 година од песниковог рођења и 35 година књижевног рада) Чубура међу голубовима (Либерова поезија и цртежи) Јужни булевар (објављена после песникове смрти, приредила ју је Либерова супруга и верни пратилац Ксенија).

Tvrd povez sa omotom, nova, veci format izdavac CID Podgorica grupa autora Zoran Gavrić: Reč unapred Zoran Gavrić: Na kraju mita o dvodelnom Rembrantu Jan Bjalostocki: Novi pogled na Rembrantovu ikonografiju Ketrin B. Skalen: Rembrantova reformacija katoličke teme - ispovednički i pokajnički sveti Jeronim Lars Olof Larson: Portreti koji govore: Zapažanja o nekim Rembrantovim portretima Maks Imdal: Govorenje i slušanje kao scensko jedinstvo - zapažanja sobzirom na Rembrantov Čas anatomije doktora Tulpa Maks Imdal: Promena kroz podražavanje - Rembrantov crtež prema Lastmanovoj Suzani u kupanju Maks Imdal: Rembrantova Noćna straža - Razmišljanja o izvornom obliku slike Margaret Dojč Kerol: Rembrantov aristotel - Uzorni posmatrač Kenet M. Krejg: Rembrant i zaklani vo Volfgang Štehov: Rembrantovi prikazi Večere u Emausu Alojz Rigl: Rembrant: Staalmeesters Maks Imdal: Režija i struktura na poslednjim Rembrantovim i Halsovim grupnim portretima Bendžamin Binstok: Videće predstave ili skriveni majstor na Rembrantovim Predstavnicima Zoran Gavrić: O boji, svetlosti i houding u Rembrantovom slikarstvu K4

Manuel Cabré Hardcover – January 1, 1980 Spanish Edition by Juan Calzadilla (Author) Hardcover — Manuel Cabré by Juan Calzadilla. Ediciones Armitano. 1975. Hardcover. 232 pages. 140 illustraciones a color y 20 en blanco y negro. Increiblemente conservado. Nuevo!!! De la figura central del Círculo de Bellas Artes, Manuel Cabré, uno de los más importantes protagonistas del hasta entonces casi desconocido género paisajístico en Venezuela, trata este libro conformado por cuatro fuentes explicativas: un discurso crítico que, sin desmedro de la visión y evolución estilísticas globales del artista, se detiene en el análisis de algunas obras especialmente representativas; la propia palabra de Cabré, recogida por J. Calzadilla, con la cual se deja invalorables testimonios acerca de los conceptos creativos del artista, así como un anecdotario que facilita la comprensión histórica de esa época; una cronología precisa y resumida, y por último, la serie de excelentes reproducciones de las obras dedicadas a la exploración plástica de nuestro entorno, por parte de este gran maestro. Solicita fotos adicionales TVRD POVEZ,veliki format, 1h

Не дешава се често да се о једном песнику, посебно не рок песнику, у часу када је он, упркос свему, и даље стваралачки присутан – напише и објави докторска дисертација. Не дешава се пак често ни Бранимир Џони Штулић. Ни 30 година пошто је највећи песник југословенског рока напустио простор Балкана, одлучан у идеји да јавно не наступа, интересовање публике за његово дело не јењава. Напротив, и данас је (све)присутан. У овој књизи, заснованој на истраживањима која су претходила одбрани прве докторске дисертације о Штулићу, анализирају се његово поетско дело, животне епизоде, лутања, трагања – сусрети који су имали улогу у развоју песничке идеје и поетског израза култног аутора. (330 стр, илустровано) Милан Младеновић иде у ред аутора који су остварили највеће домете српске и југословенске рок поезије. Након увида у основне елементе Миланове поетике и њеног развоја, те утицаја његових сарадника, готово једнако моћних индивидуалаца и креативаца, следи појединачна књижевнотеоријска анализа жанровски карактеристичних песама овог аутора, а затим и свеобухватна типолошка подела комплетног опуса према изворима инспирације, те прегледна анализа одабране дискографије ЕКВ са увидом у њен музиколошки и књижевни сегмент. Закључно поглавље нуди детаљан преглед и анализу медијске рецепције стваралаштва овог врхунског рок аутора, чије ванвременско дело поседује изузетну вредност и снажан утицај на генерације савременика и млађе, све до данас. (230 стр, илустровано)

-

Kolekcionarstvo i umetnost chevron_right Knjige

Knjiga koja je u trenu postala bestseler New York Timesa. Raspamećujuće zabavna, opasno inteligentna knjiga o filmu, jedinstvena i kreativna kao i ostala dela Kventina Tarantina. Pored toga što se ubraja među najslavnije savremene sineaste, Kventin Tarantino je možda osoba koja najzanosnije i sa najviše entuzijazma širi ljubav prema filmu. Godinama je napominjao da će se na kraju posvetiti pisanju knjiga o filmovima. Kucnuo je čas za to, a Bioskopska promišljanja odgovor su svim željama i nadama njegovih strasnih poklonika i ljubitelja filma. Organizovana oko ključnih američkih filmova iz sedamdesetih godina, koje je prvi put gledao kao mladi bioskopski gledalac, ova knjiga je intelektualno rigoriozna i pronicljiva koliko i razigrana i zabavna. Istovremeno filmska kritika, filmska teorija, reportraža, divan lični istorijat, napisana je jedinstvenim glasom koji se odmah prepoznaje kao Tarantinov. „Opako zabavno... Tarantino zna šta mu se dopada i mami čitaoca s lakoćom... Izuzetna pohvala prljavih i jezivih filmova njegove mladosti.“ – San Francisco Chronicle „Nimalo ne čudi što su Tarantinovi filmski prikazi jednako snažni, pametni i iznenađujući kao i njegovi filmovi: u izvesnom smislu on je godinama pisao i jedno i drugo... Tarantinova kritička inteligencija istovremeno prelama i odražava svetlost... Tarantino neumoljivo slavi ona prljavija zadovoljstva koja bioskop nudi.“ – New York Times Book Review „Briljantno i strastveno... Tarantinova radost, velikodušnost i jedinstveno stanovište podupiru njegove argumente, a kada govori loše o svojim junacima, on to čini iz ljubavi... Oštar, pametan i opsesivan, Tarantino je strahovito zabavan i teško ga je nadmašiti.“ – Publishers Weekly

Srbija od zlata jabuka / Serbia the Golden Apple Beograd 2005. Tvrd povez, zaštitni omot,zaštitna kutija, bogato ilustrovano, tekst uporedo na srpskom i engleskom jeziku, veliki format (30 cm), 328 strana. Knjiga je nekorišćena (nova). Srbija, od zlata jabuka knjiga je najlepših pejzaža Srbije. Snimili su ih najbolji fotografi. Reke, planine, gradovi, ljudi...ova knjiga prati ih u njihovim traganjima za lepotom. A Tvorac ovde nije bio štedljiv. Srbija, od zlata jabuka knjiga je pravljena u senci srpskih zvonika koji se dižu put neba. Najlepši srpski manastiri svedoče – hramovi „bogolepi i nebotični” – o srpskoj duhovnoj vertikali, kroz vekove. Freske s njihovih zidova najlepši su poklon jednog malog naroda kulturnoj baštini Evrope. Srbija, od zlata jabuka oslikana je sa dve nijanse zlatnog – vizantijskom i baroknom. Ovde su se ukrstili svetovi, ovde su se pomešali Istok i Zapad. Duša ovog naroda rodila se u borbi mističnog i racionalnog. Nedostižni cilj ove knjige bio je da otkrije tajne srpske duše, koja miriše čas na bosiok, čas na barut. Srbija, od zlata jabuka knjiga je puna prošlosti, ovo je zemlja u kojoj prošlost „dugo traje”. Ovo je knjiga o trajanju lepote i duha u oskudnim vremenima, kao i ova što su – a kad takva nisu bila. Zeleno, sivo, plavo: Iz sliva Drine Srbija, od zlata jabuka knjiga je o precima. Ona hoće da kaže kako ova zemlja u kojoj kroz život hodimo nije naša: nasledili smo je od predaka, dugujemo je potomcima. Srbija, od zlata jabuka priča je o Srbiji. Jedna od bezbroj mogućih. Počinje od Lepenskog Vira, završava na Oplencu. Ne pitajte zašto tamo počinje, ni zašto tamo završava. Znate odgovor. I da je drugačije počela i drugačije završila, opet bi ga znali. Srbija, od zlata jabuka knjiga je u kojoj, jedne kraj drugih, stoje slike strogih klasicista, zaneseni romantizam, salonski bidermajer i seoski, bojom i optimizmom pretrpani, pejsaži naših naivaca. Da bi se videlo koje o srpskoj duši jasnije svedoče. Srbija, od zlata jabuka nije knjiga o ratovima, nego o stvaralaštvu i kulturnom nasleđu. Nekima od nas jako je stalo do takvog prevrednovanja srpske istorije. U njoj su, na primer, „najvažniji Srbi” Sveti Sava, Nikola Tesla i Ivo Andrić. Srbija, od zlata jabuka knjiga je pravljena gotovo dve godine. Ovo je njena „stota” verzija. Kako da budemo sigurni da je bolja od prve. Jer, kad kažete „Srbija” svako pomisli na nešto drugo. Setite se toga kad njenim autorima budete stavljali primedbe. I nemojte nam suditi suviše strogo. Srbija, od zlata jabuka knjiga je pravljena s ljubavlju. „Nekako oštro i bistrorečno ljubavi je delo”. Ne terajte nas da odgovaramo da li je ova knjiga „nekako oštra i bistrorečna”. Ne znamo, Bog zna. Srbija, od zlata jabuka bila je zahtevna za pravljenje, pa će biti takva i za čitanje. Oni koji u Srbiju nemaju vere i nade, bolje da se ne dotiču njenih korica. Srbija, od zlata jabuka svoju će svrhu ispuniti tek ako je, posle čitanja, poklonite nekom ko Srbiju voli manje od Vas, i još je manje razume – ona je pravljena protiv svake bahatosti i predrasude. A puno je o Srbiji predrasuda i prema Srbiji bahatosti. I kod nas a kamoli kod drugih. Srbija, od zlata jabuka projekat je koji se svojim krajem ne završava. Naša izdavačka kuća uveliko priprema sličnu monografiju na temu Srbija danas. Ne ulazimo u taj izdavački i urednički posao bez straha i treme. Hoćemo li uspeti da napravimo ovaj nastavak Zlatne jabuke. Neko mora.

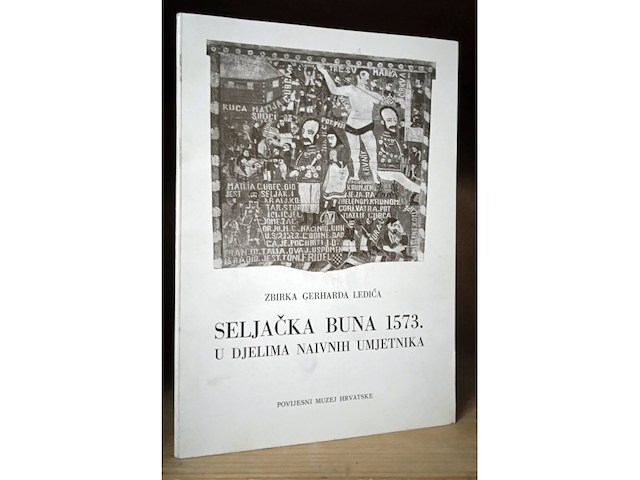

z3 - Slika na naslovnoj strani : Prikaz seljačke bune na velikom reljefu koji je 1912. godine izradio samouki seoski umjetnik Antun Fridel iz sela Bukovja kod Pušće Bistre u Hrvatskom zagorju. Ovo je ujedno njegova prva izložba. = - Slika na pisljednjoj strani : Kao spomenar i sjećanje na proslavu 400-godišnjice seljačke bune mogla bi poslužiti ova glava Matije Gupca (kao ukrasni kip , pozdravni bilikum , vaza , čaša). Po zamisli pokretača ove akcije izradio ju je nadareni seljak i lončar Franjo Batelja iz Rastoka kod Sv. Jane, općina Jaska. = - Povijesni muzej Hrvatske , Zagreb , 1973. = - Fotografije : Ljerka Krtelj = - Tisak : `Medicinska naklada` , Zagreb ===== - 59 str. - Meki uvez - Format : 17 × 24 cm Ledić, Gerhard, hrvatski novinar i kolekcionar (Zagreb, 5. V. 1926 – Zagreb, 23. I. 2010). Građansku školu i Trgovačku akademiju završio (1943) u Zagrebu. Kao đak bio sudionik tragičnoga Križnog puta 1945. od slovenske granice do Osijeka i natrag do Bjelovara. Novinarstvom se počeo baviti 1947. u Vjesniku. U toj je novinskoj kući proveo cijeli radni vijek, s vremena na vrijeme mijenjajući uredništva (najduže radio u Vjesniku u srijedu i Večernjem listu). Veliku popularnost stekao je rubrikom Lutajući reporter pronalazi, a pisao ju je pune 32 godine. Tragajući za neobičnostima proputovao je mnoge zemlje, te skupio značajne kolekcije knjiga i slika naivne umjetnosti. Surađivao na Televiziji Zagreb, s više od 300 putopisa i serija, kao voditelj, autor i urednik. U njegovoj biblioteci nalazi se oko 25 000 knjiga i svezaka od XV. stoljeća nadalje s raritetima tiskovina i rukopisa (pjesme Katarine Zrinske, rukopis Gundulićeva Osmana i dr.). Pisao je o naivnoj umjetnosti (Seljačka buna u djelima naivnih umjetnika Hrvatske, 1973; Ivan Lacković Croata, 1974).

Bioskopska promišljanja - Kventin Tarantino Izdavač: Laguna Broj strana: 408 Pismo: Latinica Povez: Mek Godina izdanja: 8. decembar 2023. Format: 13 x 20 cm Prevodilac: Goran Skrobonja NOVA knjiga!!! Knjiga koja je u trenu postala bestseler New York Timesa. Raspamećujuće zabavna, opasno inteligentna knjiga o filmu, jedinstvena i kreativna kao i ostala dela Kventina Tarantina. Pored toga što se ubraja među najslavnije savremene sineaste, Kventin Tarantino je možda osoba koja najzanosnije i sa najviše entuzijazma širi ljubav prema filmu. Godinama je napominjao da će se na kraju posvetiti pisanju knjiga o filmovima. Kucnuo je čas za to, a Bioskopska promišljanja odgovor su svim željama i nadama njegovih strasnih poklonika i ljubitelja filma. Organizovana oko ključnih američkih filmova iz sedamdesetih godina, koje je prvi put gledao kao mladi bioskopski gledalac, ova knjiga je intelektualno rigoriozna i pronicljiva koliko i razigrana i zabavna. Istovremeno filmska kritika, filmska teorija, reportraža, divan lični istorijat, napisana je jedinstvenim glasom koji se odmah prepoznaje kao Tarantinov. „Opako zabavno... Tarantino zna šta mu se dopada i mami čitaoca s lakoćom... Izuzetna pohvala prljavih i jezivih filmova njegove mladosti.“ – San Francisco Chronicle „Nimalo ne čudi što su Tarantinovi filmski prikazi jednako snažni, pametni i iznenađujući kao i njegovi filmovi: u izvesnom smislu on je godinama pisao i jedno i drugo... Tarantinova kritička inteligencija istovremeno prelama i odražava svetlost... Tarantino neumoljivo slavi ona prljavija zadovoljstva koja bioskop nudi.“ – New York Times Book Review „Briljantno i strastveno... Tarantinova radost, velikodušnost i jedinstveno stanovište podupiru njegove argumente, a kada govori loše o svojim junacima, on to čini iz ljubavi... Oštar, pametan i opsesivan, Tarantino je strahovito zabavan i teško ga je nadmašiti.“ – Publishers Weekly

Spoljašnjost kao na fotografijama, unutrašnjost u dobrom i urednom stanju! Vasilije Jordan - Josip Depolo Format: 26 x 32 cm, 264 str. Izdavač: Grafički zavod Hrvatske, 1982 Tvrdi povez Reprodukcije u boji Autori: Josip Depolo Patrick Waldberg Matko Peić Grgo Gamulin Saša Vereš Veno Zlamalik Ive Šimat Banov Radoslav Putar Jelena Uskoković Željo Sabol Stephane Rey Alain Bosquet J.M. Lo Duca Jacques Collard Monografija u odličnom stanju Vasilije Josip Jordan (Zagreb, 1. ožujka 1934. – Zagreb, 12. ožujka 2019.) bio je hrvatski akademski slikar, grafičar, kazališni scenograf i likovni pedagog.[1] Životopis Rodio se 1. ožujka 1934. godine u Zagrebu u obitelji slovenskih korijena. Školu primijenjene umjetnosti završio je 1953. godine. U Zagrebu je diplomirao na Akademiji likovnih umjetnosti u klasi profesora Ljube Babića. Za profesore je imao poznate umjetnike kao što su Krsto Hegedušić, Vjekoslav Parać, Vid Mihičić, Matko Peić i ine. Od 1960. započinje njegova profesionalna karijera samostalnog umjetnika. Prvi put je izlagao - s mladima - 1958. godine, dok je samostalno prvi put izložio svoja djela 1961. godine.[2] Bilo je to u Zagrebu u Gradskoj galeriji suvremene umjetnosti. Za tu je izložbu i sentimentalno vezan jer je na njoj upoznao svoju buduću suprugu.[3] Ukupno je samostalno izlagao više od stotinjak puta u domovini i inozemstvu. Likovni kritičari su ga uvrstili u slikare poetskog nadrealizma. Europski galeristi su ga prepoznali. Uvršten je u antologije figurativnog slikarstva 20. stoljeća. O njemu su pisali Giorgio Segato, Alain Bosquet, Stephane Rey, Paul Caso i ini. Članci o o Jordanovom slikarstvu izlazili su i u novinama kao što su to Le Soir i Le Figaro. Bavio se i grafikom i ostavio je iznimno brojne mape. Okušao se i u kazalištu kao scenograf. Napravio je scenografiju Verdijeve opere `Simon Boccanegra` u HNK-u Zagreb.[1] Bio je redovni profesor katedre za crtanje i slikanje na Akademiji likovnih umjetnosti. U istoj ustanovi bio je dekan. Sredinom 1990-ih skupa sa Stipom Sikiricom i Miroslavom Šutejom suosnivač Akademije likovnih umjetnosti u Širokom Brijegu gdje je bio i pročelnik studija za slikarstvo te dekan. [1] Ostavio je traga u sakralnoj umjetnosti: zagrebačkoj crkvi sv. Antuna izradio je četrnaest postaja Križnog puta, u zagrebačkoj kapeli sv. Dizme, crkvi sv. Frane u Splitu, crkvi sv. Marka na Plehanu, crkvi sv. Franje u Tuzli, župnoj crkvi u Osoru i dr. Djela su mu i u Vatikanskom muzeju sakralne umjetnosti. Autor je svečanog zastora Harmica u zagrebačkom Hrvatskom narodnom kazalištu. Zastor je izveo Rudi Labaš. Preminuo je 12. ožujka 2019. u 86. godini.

NOVA URAMLJENA IKONA BOGORODICE SA ISUSOM Dimenzije ikone su 29,8cmx22,8cm,pozadi ima metalni trougao da se može zakači na ekser na zidu. Najprije par riječi o roditeljima Majke Božje. Njezina majka Sveta Ana rođena je u Betlehemu iz roda kralja Davida. Od djetinjstva je bila urešena svim krepostima. Dobro je poznavala Sveto Pismo i njegova otajstva. Žarko je molila da dođe Spasitlej. Po poruci Arkanđela Gabrijela uzima Svetog Joakima za muža. Živjeli su u Nazaretu. Dugo nisu imali potomastva. Učinili su zavjet da će Bogu posvetiti svoje dijete, poput majke Samuelove. Arkanđeo Gabrijel se ukaza Svetoj Ani kao najljepši mladić. Javlja joj da je Svevišnji Gospodin uslišao njezine molitve: “Ti i Jopakim ponizili ste se u svojim prošnjama, zato će vam Svevišnji velikom darežljivošću ispuniti vaše želje. Ustrajte u molitvama. Znaj, kako sam i Joakimu već navijestio – on će imati Blaženu i Blagoslovljenu Kćerku. Ali njemu Gospodin nije otkrio tajnu, njemu nije objavljeno da će Ona biti Majka Mesije, stoga moraš ovu tajnu čuvati.” Za vrijeme Marijina začeća Sveta Ana je imala 44, a Sveti Joakim 66 godina. Taj događaj Crkva slavi velikom svetkovinom 8. prosinca. Stoljećima se rođendan Blažene Djevice Marije spominje 8. rujna. Nebeska Kraljica je koncem dvadesetog stoljeća objavila da je Njezin datum rođenja bio 5. kolovoza -na koji je dan par stoljeća kasnije učinila u Rimu čudo snijega na mjestu gradnje prve crkve sebi u čast. Po savjetu Neba Sveta Ana je spoznala da je dužnost da svojoj kćerki dade ime Mirjam – Marija, što znači Zvijezda mora. Nekoliko dana prije, nego li je Bl. Djevica Marija navršila tri godine, Sveta Ana u zanosu primi od Boga nalog, da izvrši zavjet te Kćerku zadnji dan njene treće godine prikaže u jeruzalemskon Hramu. Tog se događaja spominjemo u bogoslužju 21. studenog, kada je na taj dan posvećena u Jeruzalemu crva Sveta Marija Nova ( godine 543.) pokraj jeruzalemskog Hrama. Sveta Ana je završila zemaljski život u 56. godini sa ovim riječima svojoj Kćeri: “Baštinu Joanima i Ane dijeli sa siromasima. Tajne svoje čuvaj u dubini Srca svojega i moli neprestance Svemogućega da pošalje na svijet spasenje po obećanom Mesiji.!” Po Božjem promislu kad je Djevici Mariji bilo 14 godina zaručena je sa Svetim Josipom iz Nazareta koji je imao 33 godine. Prošlo je šest mjeseci i 17 dana od zaruka kada se – 25. ožujka po pristanku Josipove zaručnice Marije, u njezinom krulu začeo primivši tijelo Sin Božji. Djevica je postala živi ciborij u koji silazi Kruh koji dolazi s Neba. Tijelo Gospodinovo postalo je tijelom u krilu Bezgrešne, koja je to ostala od časa začerća. Najčišća Djevica je prihvatila Nebo u svoje krilo odijevajući svojim tijelom Riječ Očevu nakon božanskog vjenčanja s Duhom Svetim. Tako je Blažena Djevica postala prvo živo Svetohranište Presvetog Trojstva gdje se Otac Nebeski neprestano slavi, Sin savršeno ljubi a Duh Sveti u potpunosti posjeduje. 25 prosinca Djevica Marija rodi u Betlehemu Spasitelja. Prema objavi Isusa Krista Službenici Božjoj Mariji Agredskskoj prošlo je od stvaranja Adama do Božića ukupno 5199 godina.Činom stalne vjere Bogorodica je u svom Sinu Isusu vidjela svog Boga i duboko Mu se ljubavlju klanjala:- kao sitnom zametku dajući Mu svoju krv i tijelo; nakon rođenja promatrajući Ga u jaslama siromašne spilje; dječaku Isusu koji raste, mladiću koji se razvija te mladom čovjeku nad svakodnevnim tesarskim poslom i Mesiji koji vrši svoje javno poslanje. Klanjala se Isusu primivši Ga u prilikama Kruha i Vina nakon Apostola na Posljednjoj Večeri. Kad su Isusa svukli na Kalvariji Majka Mesije daruje svoj bijeli veo da se zaštiti Sin u svojoj stidljivosti. Tako je na Veliki Petak bila prisutna kod Isusovog prikazivanja Njegove krvave žrtve na Križu. Osobitim načinom ostale su u njezinu Srcu slike Muke Isusove redom kako su slijedile te je kod razmatranja uvijek osjećala one boli, koje je podnosio njezin Božanski Sin. Iz ljubavi prema Bogu trpjela je više nego Mučenci ili Sveci. Svaki petak duboko je Gospa proživljaval smrt i ukop svojeg Sina. U svojoj sobi bi započela razmatranje kako je Gospodin prao noge svojim učenicima te proslijedila do sjećanja na prvi susret sa Uskrslim Sinom. Nakon silaska Duha Svetoga Marija je skoro svaki dan najsavršenije sudjelovala u prikazivanju Nekrvne Žrtve koju je obično slavio Sveti Ivan. Najprije bi se molili Psalmi i čitali odlomci Starog Zavjeta Pretvorba je bila kao i danas. Službenica Božja Marija Agredska spominje da je vidjela kako se Bogorodica tri puta do zemlje poklanjala i tada s godućom ljubavlju primala Nebreski Kruh.. (Poklon do zemlje prije Svete Pričesti navodi kao redovitu praksu u svoje vrijeme Sveti Augustin). Nakon Pričesti povukla bi se Bogorodica u svoju sobu i ostala u svojoj sobi čak po tri sata. Tako žarka bijaše njena priprava i zahvala Svete Pričesti da je njezin Božanski Sin na to odgovarao osobnom posjetom Svojoj Majci. Kroz to vrijeme zanosnog motrenja Sveti Ivan je viđao kako blistave sjajne zrake izlaze iz Majke Božje. Presveta Djevica Marija je zadnjih godina svojega života vrlo malo jela i spavala. Spavala bi po jedan sat a jela par komadića kruha i malo ribe. Ali je brižno spremala hranu i majčinski dvorila Apostola Ivana. Prva je živjela od Svete Pričesti, Ona je mogla živjeti samo od Nebeske Hrane što će se ponoviti kroz stoljeć kod Svetaca koji su posebno častili Oltarski Sakramenat. U ovom prikazu će o tim karizmama biti riječ. Od 16. do 25. pripravljala se Bogorodica na spoemn Utjelovljenja te je samo primala Svetu Pričest i bila bez jela i pila. Majka Velikog Svećenika Isusa biva prisutna kod svakog oltara kada Isus u osobi svojeg službenika žrtvuje Sebe za sve nas na nekrvni način u Svetoj Misi. Isus sa slavnim Tijelom ostaje Marijin Sin, koji je nama za ljubav prisutan pod bijelom pojavom posvećenog Kruha. Bogorodica je prostrta pred svakim Svetohraništem u činu vječnog klanjaja i zadovoljštine sa Zborovima Anđela i mnoštvom Svetih. Blažena Djevica, Majka Emanuela - Boga s nama, je naša Majka Euharistije. Zemaljski život završila je u pedeset petoj godini, 22 godine nakon Isusova uzašašća. Dušom i tijelom uzeta je u Nebo i okrunjena kao Kraljica Anđela i Svetih 15. kolovoza kada Crkva slavi svetkovinu Uznesenja Blažene Djevice Marije u Nebo.

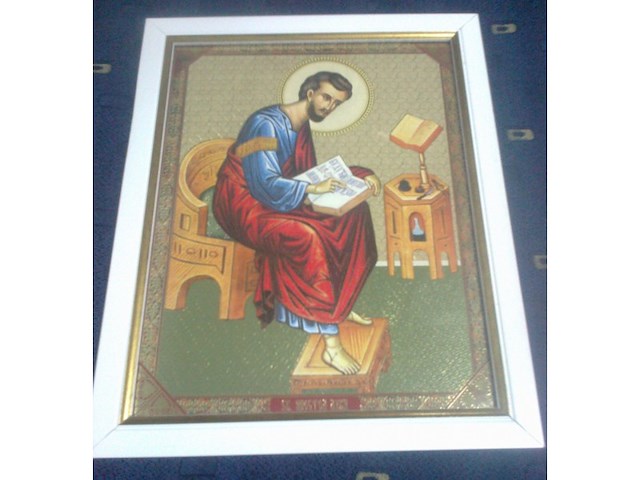

NOVA URAMLJENA IKONA-SVETI APOSTOL LUKA Dimenzije ikone su 30,7cm SA 24,4cm,pozadi ima metalni trougao da se može zakači na ekser na zidu-svaka ikona koju prodajem ima staklo-tj.uramljena je sa staklom. Свети апостол и јеванђелист Лука Свети Еванђелист Лука беше родом из Антиохије Сиријске. У младости он добро изучи грчку философију, медицину и живопис. Он одлично знађаше египатски и грчки језик. У време делатности Господа Исуса на земљи Лука дође из Антиохије у Јерусалим. Живећи као човек међу људима, Господ Исус сејаше божанско семе спаооносног учења свог, а Лукино срце би добра земља за то небеско семе. И оно проклија у њему, ниче и донесе стоструки плод. Јер Лука, гледајући Спаситеља лицем у лице и слушајући Његову божанску науку, испуни се божанске мудрости и божанског знања, које му не дадоше ни јелинске ни египатске школе: он познаде истинитог Бога, верова у Њега, и би увршћен у Седамдесет апостола, и послат на проповед. О томе он сам говори у Еванђељу свом: Изабра Господ и других Седамдесеторицу, и поana их по два и два пред лицем својим у сваки град и место куда шћаше сам доћи (Лк. 10, 1). И свети Лука, наоружан од Господа силом и влашћу да проповеда Еванђеље и чини чудеса, хођаше `пред лицем` Господа Исуса Христа, светом проповеђу припремајући пут Господу и убеђујући људе да је на свет дошао очекивани Месија. У последње дане земаљског живота Спаситељевог, када Божански Пастир би ударен и овце се Његове од страха разбегоше, свети Лука се налажаше у Јерусалиму, тугујући и плачући за Господом својим, који благоволи добровољно пострадати за спасење наше. Али се његова жалост убрзо окрену на радост: јер васкрсли Господ, у сами дан Васкрсења Свог јави се њему када је с Клеопом ишао у Емаус, и вечном радошћу испуни срце његово, о чему он сам подробно говори у Еванђељу свом (Лк. 24, 13-35). По силаску Светога Духа на апостоле, свети Лука остаде неко време са осталим апостолима у Јерусалиму, па крену у Антиохију, где је већ било доста хришћана. На том путу он се задржа у Севастији,[1] проповедајући Еванђеље спасења. У Севастији су почивале нетљене мошти светога Јована Претече. Полазећи из Севастије, свети Лука је хтео да те свете мошти узме и пренесе у Антиохију, али тамошњи хришћани не дозволише да остану без тако драгоцене светиње. Они допустише, те свети Лука узе десну руку светога Крститеља, под коју је Господ при крштењу Свом од Јована преклонио Своју Божанску Главу. Са тако скупоценим благом свети Лука сгимсе у свој завичај, на велику радост антиохијских хришћана. Из Антиохије свети Лука отпутова тек када постаде сарадник и сапутник светог апостола Павла. To се догодило у време Другог путовања светога Павла.[2] Тада свети Лука отпутова са апостолом Павлом у Грчку на проповед Еванђеља. Свети Павле остави светога Луку у Македонском граду Филиби, да ту утврди и уреди Цркву. Од тога времена свети Лука остаде неколико година у Македонији,[3] проповедајући и ширећи хришћанство. Када свети Павле при крају свог Трећег апостолског путовања поново посети Филибу, он посла светог Луку у Коринт ради скупљања милостиње за сиромашне хришћане у Палестини. Скупивши милостињу свети Лука са светим апостолом крену у Палестину, посећујући успут Цркве, које су се налазиле на острвима Архипелага, на обалама Мале Азије, у Финикији и Јудеји. А када апостол Павле би стављен под стражу у Палестинском граду Кесарији, свети Лука остаде поред њега. He напусти он апостола Павла ни онда, када овај би упућен у Рим, на суд ћесару. Он је заједно са апостолом Павлом подносио све тешкоће путовања по мору, подвргавајући се великим опасностима (ср. Д. А. 27 и 28 глава). Дошавши у Рим, свети Лука се такође налазио поред апостола Павла, и заједно са Марком, Аристархом и неким другим сапутницима великог апостола народа, проповедао Христа у тој престоници старога света.[4] У Риму је свети Лука написао своје Еванђеље и Дела Светих Апостола.[5] У Еванђељу он описује живот и рад Господа Исуса Христа не само на основу онога што је сам видео и чуо, него имајући у виду све оно што предаше `први очевидци и слуге речи` (Лк. 1, 2). У овом светом послу светог Луку руковођаше свети апостол Павле, и затим одобри свето Еванђеље написано светим Луком. Исто тако и Дела Светих Апостола свети Лука је, како каже црквено предање, написао по налогу светог апостола Павла.[6] После двогодишњег затвора у узама римским, свети апостол Павле би пуштен на слободу, и оставивши Рим он посети неке Цркве које је био основао раније. На овоме путу свети Лука га је пратио. He прође много времена а цар Нерон подиже у Риму жестоко гоњење хришћана. У то време апостол Павле по друга пут допутова у Рим, да би својом речју и примером ободрио и подржао гоњену Цркву. Но незнабошци га ухватише и у окове бацише. Свети Лука и у ово тешко време налажаше се неодступно поред свог учитеља. Свети апостол Павле пише о себи као о жртви која је већ на жртвенику. Ја већ постајем жртва, пише у то време свети апостол своме ученику Тимотеју, и време мога одласка наста. Постарај се да дођеш брзо к мени: јер ме Димас остави, омилевши му садашњи свет, и отиде у Солун; Крискент у Галатију, Тит у Далмацију; Лука је сам код мене (2 Тм. 4, 6.10). Врло је вероватно да је свети Лука био очевидац и мученичке кончине светог апостола Павла у Риму. После мученичке кончине апостола Павла свети Лука је проповедао Господа Христа у Италији, Далмацији, Галији, а нарочито у Македонији, у којој се и раније трудио неколико година. Поред тога благовестио је Господа Христа у Ахаји.[7] У старости својој свети Лука отпутова у Египат ради проповеди Еванђеља. Тамо он благовестећи Христа претрпе многе муке и изврши многе подвиге. И удаљену Тиваиду он просвети вечном светлошћу Христова Еванђеља. У граду Александрији он рукоположи за епископа Авилија на место Аниана, рукоположеног светим Еванђелистом Марком. Вративши се у Грчку, свети Лука устроји Цркве нарочито у Беотији,[8] рукоположи свештенике и ђаконе, исцели болесне телом и душом. Светом Луки беше осамдесет четири година, када га злобни идолопоклоници ударише на муке Христа ради и обесише о једној маслини у граду Тиви (= Теби) Беотијској. Чесно тело његово би погребено у Тиви, главном граду Беотије, где од њега биваху многа чудеса. Ту су се ове свете чудотворне мошти налазиле до друге половине четвртога века, када бише пренесене у Цариград, у време цара Констанција, сина Константиновог. У четвртом веку нарочито се прочу место где су почивале чесне мошти светога Луке, због исцељивања која су се збивала од њих. Особито исцељивање од болести очију. Сазнавши о томе цар Констанције посла управитеља Египта Артемија[9] да мошти светога Луке пренесе у престоницу, што и би учињено веома свечано.[10] У време преношења ових светих моштију од обале морске у свети храм, догоди се овакво чудо. Неки евнух Анатолије, на служби у царском двору, беше дуго болестан од неизлечиве болести. Он много новаца утроши на лекаре, али исцељења не доби. А када чу да се у град уносе свете мошти светога Луке, он се од свег срца стаде молити светом апостолу и евангелисту за исцељење. Једва уставши са постеље он нареди да га воде у сусрет ковчегу са моштима светога Луке. А када га доведоше до ковчега, он се поклони светим моштима и с вером се дотаче кивота, и тог часа доби потпуно исцељење и постаде савршено здрав. И одмах сам подметну своја рамена испод ковчега са светим моштима, те га са осталим људима носаше, и унесоше у храм светих Апостола, где мошти светога Луке бише положене под светим престолом, поред моштију светих апостола: Андреја и Тимотеја. Стари црквени писци казују, да је свети Лука, одазивајући се побожној жељи ондашњих хришћана, први живописао икону Пресвете Богородице са Богомладенцем Господом Исусом на њеним рукама, и то не једну него три, и донео их на увид Богоматери. Разгледавши их, она је рекла: Благодат Рођеног од мене, и моја, нека буду са овим иконама. Свети Лука је исто тако живописао на даскама и иконе светих првоврховних апостола Петра и Павла. И тако свети апостол и еванђелист Лука постави почетак дивном и богоугодном делу - живописању светих икона, у славу Божију, Богоматере и свих Светих, а на благољепије светих цркава, и на спасење верних који побожно почитују свете иконе. Амин. Pogledajte moju ponudu na kupindu: http://www.kupindo.com/Clan/durlanac2929/SpisakPredmeta Pogledajte moju ponudu na limundu: http://www.limundo.com/Clan/durlanac2929/SpisakAukcija

Dimenzije ikone su 29.8cm SA 24,1cm,pozadi ima metalni trougao da se može zakači na ekser na zidu-svaka ikona koju prodajem ima staklo-tj.uramljena je sa staklom. Свети апостол и јеванђелист Лука Свети Еванђелист Лука беше родом из Антиохије Сиријске. У младости он добро изучи грчку философију, медицину и живопис. Он одлично знађаше египатски и грчки језик. У време делатности Господа Исуса на земљи Лука дође из Антиохије у Јерусалим. Живећи као човек међу људима, Господ Исус сејаше божанско семе спаооносног учења свог, а Лукино срце би добра земља за то небеско семе. И оно проклија у њему, ниче и донесе стоструки плод. Јер Лука, гледајући Спаситеља лицем у лице и слушајући Његову божанску науку, испуни се божанске мудрости и божанског знања, које му не дадоше ни јелинске ни египатске школе: он познаде истинитог Бога, верова у Њега, и би увршћен у Седамдесет апостола, и послат на проповед. О томе он сам говори у Еванђељу свом: Изабра Господ и других Седамдесеторицу, и поana их по два и два пред лицем својим у сваки град и место куда шћаше сам доћи (Лк. 10, 1). И свети Лука, наоружан од Господа силом и влашћу да проповеда Еванђеље и чини чудеса, хођаше `пред лицем` Господа Исуса Христа, светом проповеђу припремајући пут Господу и убеђујући људе да је на свет дошао очекивани Месија. У последње дане земаљског живота Спаситељевог, када Божански Пастир би ударен и овце се Његове од страха разбегоше, свети Лука се налажаше у Јерусалиму, тугујући и плачући за Господом својим, који благоволи добровољно пострадати за спасење наше. Али се његова жалост убрзо окрену на радост: јер васкрсли Господ, у сами дан Васкрсења Свог јави се њему када је с Клеопом ишао у Емаус, и вечном радошћу испуни срце његово, о чему он сам подробно говори у Еванђељу свом (Лк. 24, 13-35). По силаску Светога Духа на апостоле, свети Лука остаде неко време са осталим апостолима у Јерусалиму, па крену у Антиохију, где је већ било доста хришћана. На том путу он се задржа у Севастији,[1] проповедајући Еванђеље спасења. У Севастији су почивале нетљене мошти светога Јована Претече. Полазећи из Севастије, свети Лука је хтео да те свете мошти узме и пренесе у Антиохију, али тамошњи хришћани не дозволише да остану без тако драгоцене светиње. Они допустише, те свети Лука узе десну руку светога Крститеља, под коју је Господ при крштењу Свом од Јована преклонио Своју Божанску Главу. Са тако скупоценим благом свети Лука сгимсе у свој завичај, на велику радост антиохијских хришћана. Из Антиохије свети Лука отпутова тек када постаде сарадник и сапутник светог апостола Павла. To се догодило у време Другог путовања светога Павла.[2] Тада свети Лука отпутова са апостолом Павлом у Грчку на проповед Еванђеља. Свети Павле остави светога Луку у Македонском граду Филиби, да ту утврди и уреди Цркву. Од тога времена свети Лука остаде неколико година у Македонији,[3] проповедајући и ширећи хришћанство. Када свети Павле при крају свог Трећег апостолског путовања поново посети Филибу, он посла светог Луку у Коринт ради скупљања милостиње за сиромашне хришћане у Палестини. Скупивши милостињу свети Лука са светим апостолом крену у Палестину, посећујући успут Цркве, које су се налазиле на острвима Архипелага, на обалама Мале Азије, у Финикији и Јудеји. А када апостол Павле би стављен под стражу у Палестинском граду Кесарији, свети Лука остаде поред њега. He напусти он апостола Павла ни онда, када овај би упућен у Рим, на суд ћесару. Он је заједно са апостолом Павлом подносио све тешкоће путовања по мору, подвргавајући се великим опасностима (ср. Д. А. 27 и 28 глава). Дошавши у Рим, свети Лука се такође налазио поред апостола Павла, и заједно са Марком, Аристархом и неким другим сапутницима великог апостола народа, проповедао Христа у тој престоници старога света.[4] У Риму је свети Лука написао своје Еванђеље и Дела Светих Апостола.[5] У Еванђељу он описује живот и рад Господа Исуса Христа не само на основу онога што је сам видео и чуо, него имајући у виду све оно што предаше `први очевидци и слуге речи` (Лк. 1, 2). У овом светом послу светог Луку руковођаше свети апостол Павле, и затим одобри свето Еванђеље написано светим Луком. Исто тако и Дела Светих Апостола свети Лука је, како каже црквено предање, написао по налогу светог апостола Павла.[6] После двогодишњег затвора у узама римским, свети апостол Павле би пуштен на слободу, и оставивши Рим он посети неке Цркве које је био основао раније. На овоме путу свети Лука га је пратио. He прође много времена а цар Нерон подиже у Риму жестоко гоњење хришћана. У то време апостол Павле по друга пут допутова у Рим, да би својом речју и примером ободрио и подржао гоњену Цркву. Но незнабошци га ухватише и у окове бацише. Свети Лука и у ово тешко време налажаше се неодступно поред свог учитеља. Свети апостол Павле пише о себи као о жртви која је већ на жртвенику. Ја већ постајем жртва, пише у то време свети апостол своме ученику Тимотеју, и време мога одласка наста. Постарај се да дођеш брзо к мени: јер ме Димас остави, омилевши му садашњи свет, и отиде у Солун; Крискент у Галатију, Тит у Далмацију; Лука је сам код мене (2 Тм. 4, 6.10). Врло је вероватно да је свети Лука био очевидац и мученичке кончине светог апостола Павла у Риму. После мученичке кончине апостола Павла свети Лука је проповедао Господа Христа у Италији, Далмацији, Галији, а нарочито у Македонији, у којој се и раније трудио неколико година. Поред тога благовестио је Господа Христа у Ахаји.[7] У старости својој свети Лука отпутова у Египат ради проповеди Еванђеља. Тамо он благовестећи Христа претрпе многе муке и изврши многе подвиге. И удаљену Тиваиду он просвети вечном светлошћу Христова Еванђеља. У граду Александрији он рукоположи за епископа Авилија на место Аниана, рукоположеног светим Еванђелистом Марком. Вративши се у Грчку, свети Лука устроји Цркве нарочито у Беотији,[8] рукоположи свештенике и ђаконе, исцели болесне телом и душом. Светом Луки беше осамдесет четири година, када га злобни идолопоклоници ударише на муке Христа ради и обесише о једној маслини у граду Тиви (= Теби) Беотијској. Чесно тело његово би погребено у Тиви, главном граду Беотије, где од њега биваху многа чудеса. Ту су се ове свете чудотворне мошти налазиле до друге половине четвртога века, када бише пренесене у Цариград, у време цара Констанција, сина Константиновог. У четвртом веку нарочито се прочу место где су почивале чесне мошти светога Луке, због исцељивања која су се збивала од њих. Особито исцељивање од болести очију. Сазнавши о томе цар Констанције посла управитеља Египта Артемија[9] да мошти светога Луке пренесе у престоницу, што и би учињено веома свечано.[10] У време преношења ових светих моштију од обале морске у свети храм, догоди се овакво чудо. Неки евнух Анатолије, на служби у царском двору, беше дуго болестан од неизлечиве болести. Он много новаца утроши на лекаре, али исцељења не доби. А када чу да се у град уносе свете мошти светога Луке, он се од свег срца стаде молити светом апостолу и евангелисту за исцељење. Једва уставши са постеље он нареди да га воде у сусрет ковчегу са моштима светога Луке. А када га доведоше до ковчега, он се поклони светим моштима и с вером се дотаче кивота, и тог часа доби потпуно исцељење и постаде савршено здрав. И одмах сам подметну своја рамена испод ковчега са светим моштима, те га са осталим људима носаше, и унесоше у храм светих Апостола, где мошти светога Луке бише положене под светим престолом, поред моштију светих апостола: Андреја и Тимотеја. Стари црквени писци казују, да је свети Лука, одазивајући се побожној жељи ондашњих хришћана, први живописао икону Пресвете Богородице са Богомладенцем Господом Исусом на њеним рукама, и то не једну него три, и донео их на увид Богоматери. Разгледавши их, она је рекла: Благодат Рођеног од мене, и моја, нека буду са овим иконама. Свети Лука је исто тако живописао на даскама и иконе светих првоврховних апостола Петра и Павла. И тако свети апостол и еванђелист Лука постави почетак дивном и богоугодном делу - живописању светих икона, у славу Божију, Богоматере и свих Светих, а на благољепије светих цркава, и на спасење верних који побожно почитују свете иконе. Амин. Pogledajte moju ponudu na kupindu: http://www.kupindo.com/Clan/durlanac2929/SpisakPredmeta Pogledajte moju ponudu na limundu: http://www.limundo.com/Clan/durlanac2929/SpisakAukcija