Pratite promene cene putem maila

- Da bi dobijali obaveštenja o promeni cene potrebno je da kliknete Prati oglas dugme koje se nalazi na dnu svakog oglasa i unesete Vašu mail adresu.

1-4 od 4 rezultata

Broj oglasa

Prikaz

1-4 od 4

1-4 od 4 rezultata

Prikaz

Prati pretragu "15-36"

Vi se opustite, Gogi će Vas obavestiti kad pronađe nove oglase za tražene ključne reči.

Gogi će vas obavestiti kada pronađe nove oglase.

Režim promene aktivan!

Upravo ste u režimu promene sačuvane pretrage za frazu .

Možete da promenite frazu ili filtere i sačuvate trenutno stanje

100 Ličnosti,ceo Komplet 1-100 brojevi od 76 do 100 jako lepo ukoriceni-videti slike Ljudi koji su promenili svet lepo ocuvano.znatno i necitano,poneki i u orginalnom celofanu 1. broj - Albert Ajnštajn 2. broj - Galileo Galilej 3. broj - Volfgang Amadeus Mocart 4. broj - Leonardo da Vinči 5. broj - Sigmund Frojd 6. broj - Aleksandar Veliki 7. broj - Vilijam Šekspir 8. broj - Čarli Čaplin 9. broj - Arhimed 10. broj - Mahatma Gandi 11. broj - Čarls Darvin 12. broj - Ernesto Če Gevara 13. broj - Pitagora 14. broj - Vinsent Van Gog 15. broj - Marko Polo 16. broj - Napoleon Bonaparta 17. broj - Nostradamus 18. broj - Merlin Monro 19. broj - Jurij Gagarin 20. broj - Elvis Prisli 21. broj - Adolf Hitler 22. broj - Tomas Edison 23. broj - Gaj Julije Cezar 24. broj - Lav Tolstoj 25. broj - Bitlsi 26. broj - Buda 27. broj - Braća Grim 28. broj - Alfred Hičkok 29. broj - Al Kapone 30. broj - Martin Luter King 31. broj - Hajnrih Šliman 32. broj - Ferdinand Porše 33. broj - Lenjin 34. broj - Antonio Gaudi 35. broj - Nikola Tesla 36. broj - Kristofer Kolumbo 37. broj - Benito Musolini 38. broj - Pablo Pikaso 39. broj - Alfred Nobel 40. broj - Karlo Veliki 41. broj - Akira Kurosava 42. broj - Petar Veliki 43. broj - Ernest Hemingvej 44. broj - Marija Kiri 45. broj - Nikita Hruščov 46. broj - Čarls Lindberg 47. broj - Žan Anri Fabr 48. broj - Dž.R.R.Tolkin 49. broj - Karl Marks 50. broj - Ludvig van Betoven 51. broj - Soićiro Honda 52. broj - Konfucije 53. broj - Josif Staljin 54. broj - Vinston Čerčil 55. broj - Isak Njutn 56. broj - Sokrat 57. broj - Roald Amundsen 58. broj - Džingis-kan 59. broj - Braća Rajt 60. broj - Abraham Linkoln 61. broj - Artur Konan Dojl 62. broj - Martin Luter 63. broj - Džon F. Kenedi 64. broj - T. E. Lorens 65. broj - Nikola Kopernik 66. broj - Ervin Romel 67. broj - Saladin 68. broj - Mustafa Kemal Ataturk 69. broj - Bejb Rut 70. broj - Džordž Vašington 71. broj - Džejms Din 72. broj - Šarl de Gol 73. broj - Čarls M. Šulc 74. broj - Ričard Nikson 75. broj - Fjodor Dostojevski 76. broj - Jovanka Orleanka 77. broj - Florens Najtingejl 78. broj - Džon D. Rokfeler 79. broj - Robert Kapa 80. broj - Neron 81. broj - Džon fon Nojman 82. broj - Gamal Abdel Naser 83. broj - Mao Cedung 84. broj - Majka Tereza 85. broj - Hanibal 86. broj - Elizabeta I 87. broj - Pol Pot 88. broj - Marija Antoaneta 89. broj - Oto fon Bizmark 90. broj - Frenklin Ruzvelt 91. broj - Ho Ši Min 92. broj - Horacije Nelson 93. broj - Ivo Andrić 94. broj - Daglas Makartur 95. broj - Haris Truman 96. broj - Oskar Šindler 97. broj - Dž.Edgar Huver 98. broj - Aleksandar Grejem Bel 99. broj - Platon 100. broj - Vuk Stefanović Karadžić

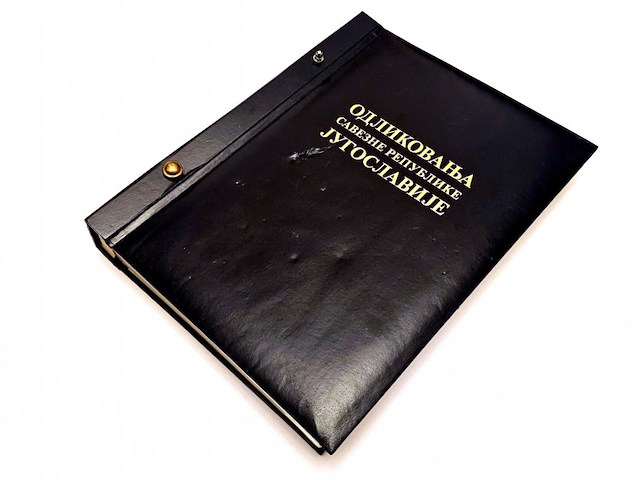

Knjiga izrađena za internu upotrebu, sa svim ordenima i pratećim statutima Savezne republike Jugoslavije Tvrd povez, veliki format (31 cm), 114 strana. Napomena: oštećenje (ogrebotina na prednjim koricama); ako se to izuzme, knjig je odlično očuvana. Izuzetno retko. Sadržaj: 1. Orden Jugoslavije 2. Orden Jugoslovenske velike zvezde 3. Orden slobode 4. Orden narodnog heroja 5. Orden Jugoslovenske zastave I stepena 6. Orden ratne zastave I stepena 7. Orden Jugoslovenske zvezde I stepena 8.nOrden zasluga za SR Jugoslaviju I stepena 9. Orden viteškog mača I stepena 10. Orden Vojske Jugoslavije I stepena 11. Odlikovanja istog ranga za zasluge u oblastima: — međunarodne političke, ekonomske i kulturne saradnje; — društvenih i humanističkih nauka; — prosvete, kulture i umetnosti; — prirodnih i tehničkih nauka Orden Nemanje I stepena Orden Njegoša I stepena Orden Vuka Karadžića I stepena Orden Tesle I stepena 12. Orden za hrabrost 13. Orden rada 14. Orden za zasluge u oblastima odbrane i bezbednosti I stepena 15. Velika odlikovanja istog ranga: Medalja Obilića Medalja časti Cvijićeva medalja Medalja belog anđela Medalja čovekoljublja 16. Orden Jugoslovenske zastave II stepena 17. Orden ratne zastave II stepena 18. Orden Jugoslovenske zvezde II stepena 19. Orden zasluga za SR Jugoslaviju II stepena 20. Orden viteškog mača II stepena 21. Orden Vojske Jugoslavije II stepena 22. Odlikovanja istog ranga za zasluge u oblastima: — međunarodne političke, ekonomske i kulturne saradnje; — društvenih i humanističkih nauka; — prosvete, kulture i umetnosti; — prirodnih i tehničkih nauka. Orden Nemanje II stepena Orden Njegoša II stepena Orden Vuka Karadžića II stepena Orden Tesle II stepena 23. Orden za zasluge u oblastima odbrane i bezbednosti II stepena 24. Orden Jugoslovenske zastave III stepena 25. Orden ratne zastave III stepena 26. Orden Jugoslovenske zvezde III stepena 27. Orden zasluga za SR Jugoslaviju III stepena 28. Orden viteškog mača III stepena 29. Orden Vojske Jugoslavije III stepena 30. Odlikovanja istog ranga za zasluge u oblastima: — međunarodne političke, ekonomske i kulturne saradnje; — društvenih i humanističkih nauka; — prosvete, kulture i umetnosti; — prirodnih i tehničkih nauka. Orden Nemanje III stepena Orden Njegoša III stepena Orden Vuka Karadžića III stepena Orden Tesle III stepena 31. Orden za zasluge u oblastima odbrane i bezbednosti III stepena 32. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu državi I stepena 33. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu u oblastima odbrane i bezbednosti I stepena 34. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu državi II stepena 35. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu u oblastima odbrane i bezbednosti II stepena 36. Medalja zarasluge u privredi I stepena 37. Medalja za zasluge u prosveti i kulturi I stepena 38. Medalja za zasluge u poljoprivredi I stepena 39. Medalja za zasluge u oblasti odbrane i bezbednosti 40. Medalja za vrline u oblasti odbrane i bezbednosti 41. Medalja za zasluge u privredi II stepena 42. Medalja za zasluge u prosveti i kulturi II stepena 43. Medalja za zasluge u poljoprivredi II stepena 44. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu državi III stepena 45. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu u oblastima odbrane i bezbednosti III stepena 46. Medalja za zasluge u privredi III stepena 47. Medalja za zasluge u prosveti i kulturi III stepena 48. Medalja za zasluge u poljoprivredi III stepena 49. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu državi IV stepena 50. Medalja za dugogodišnju revnosnu službu u oblastima odbrane i bezbednosti IV stepena

Winston S. Churchill - The Second World War (6 volume set) Cassell & Co Limited, 1948-54 tvrdi povez stanje: dobro, potpis na predlistu. The Gathering Storm (1948) Their Finest Hour (1949) The Grand Alliance (1950) The Hinge of Fate (1950) Closing the Ring (1951) Triumph and Tragedy (1953) The definitive, Nobel Prize–winning history of World War II, universally acknowledged as a magnificent historical reconstruction and an enduring work of literature From Britain`s darkest and finest hour to the great alliance and ultimate victory, the Second World War remains the most pivotal event of the twentieth century. Winston Churchill was not only the war`s greatest leader, he was the free world`s singularly eloquent voice of defiance in the face of Nazi tyranny, and it`s that voice that animates this six-volume history. Remarkable both for its sweep and for its sense of personal involvement, it begins with The Gathering Storm; moves on to Their Finest Hour, The Grand Alliance, The Hinge of Fate, and Closing the Ring; and concludes with Triumph and Tragedy. A History of the English Speaking Peoples Volume I Based on the research of modern historians as well as a wealth of primary source material, Churchill’s popular and readable A History of the English-Speaking Peoples was respected by scholars as well as the public in its day - a testament both to its integrity as a work of historical scholarship and its accessibility to laypeople. Churchill used primary sources to masterful effect, quoting directly from a range of documents, from Caesar’s invasions of Britain to the beginning of the First World War, to provide valuable insights into those figures who played a leading role in British history. In The Birth of Britain, the first of the four-volume series, Churchill guides the reader through the establishment of the constitutional monarchy, the parliamentary system, and the people who played lead roles in creating democracy in England. Table of Contents: Front matter Acknowledgments pp. v–vi Preface pp. vii–xvii Book I The Island Race Chapter I. Britannia pp. 3–14 Chapter II. Subjugation pp. 15–27 Chapter III. The Roman Province pp. 28–36 Chapter IV. The Lost Island pp. 37–54 Chapter V. England pp. 55–68 Chapter VI. The Vikings pp. 69–81 Chapter VII. Alfred the Great pp. 82–101 Chapter VIII. The Saxon Dusk pp. 102–118 Book II The Making of the Nation Chapter I. The Norman Invasion pp. 121–130 Chapter II. William the Conqueror pp. 131–140 Chapter III. Growth Amid Turmoil pp. 141–156 Chapter IV. Henry Plantagenet pp. 157–169 Chapter V. The English Common Law pp. 170–177 Chapter VI. Cœur De Lion pp. 178–189 Chapter VII. Magna Carta pp. 190–202 Chapter VIII. On the Anvil pp. 203–214 Chapter IX. The Mother of Parliaments pp. 215–223 Chapter X. King Edward I pp. 224–243 Chapter XI. Bannockburn pp. 244–251 Chapter VII. Scotland and Ireland pp. 252–261 Chapter XIII. The Long-Bow pp. 262–277 Chapter XIV. The Black Death pp. 278–286 Book III The End of the Feudal Age Chapter I. King Richard II and the Social Revolt pp. 289–307 Chapter II. The Usurpation of Henry Bolingbroke pp. 308–314 Chapter III. The Empire of Henry V pp. 315–324 Chapter IV. Joan of Arc pp. 325–333 Chapter V. York and Lancaster pp. 334–346 Chapter VI. The Wars of the Roses pp. 347–360 Chapter VII. The Adventures of Edward IV pp. 361–377 Chapter VIII. Richard III pp. 378–396 Index pp. 397–416 ________________________________________________ The Second World War Volume II Their Finest Hour Winston Churchill`s monumental The Second World War, is a six volume account of the struggle between the Allied Powers in Europe against Germany and the Axis. Told by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, this book is also the story of one nation`s heroic role in the fight against tyranny. Having learned a lesson at Munich they would never forget, the British refused to make peace with Hitler, defying him even after France had fallen and it seemed as though the Nazis were unstoppable. In Their Finest Hour, Churchill describes the invasion of France and a growing sense of dismay in Britain. Should Britain meet France`s desperate pleas for reinforcements or husband their resources in preparation for the inevitable German assault? In the book`s second half, entitled simply `Alone,` Churchill discusses Great Britain`s position as the last stronghold against German conquest: the battle for control of the skies over Britain, diplomatic efforts to draw the United States into the war, and the spreading global conflict. Acknowledgments pp. v–vi Preface pp. vii–viii Part Book IV. Renaissance and Reformation Chapter I. The Round World pp. 3–12 Chapter II. The Tudor Dynasty pp. 13–21 Chapter III. King Henry VIII pp. 22–30 Chapter IV. Cardinal Wolsey pp. 31–42 Chapter V. The Break with Rome pp. 43–56 Chapter VI. The End of the Monasteries pp. 57–68 Chapter VII. The Protestant Struggle pp. 69–81 Chapter VIII. Good Queen Bess pp. 82–95 Chapter IX. The Spanish Armada pp. 96–105 Chapter X. Gloriana pp. 106–116 Part Book V. The Civil War Chapter I. The United Crowns pp. 119–131 Chapter II. The Mayflower pp. 132–142 Chapter III. Charles I and Buckingham pp. 143–152 Chapter IV. The Personal Rule pp. 153–168 Chapter V. The Revolt of Parliament pp. 169–184 Chapter VI. The Great Rebellion pp. 185–198 Chapter VII. Marston Moor and Naseby pp. 199–207 Chapter VIII. The Axe Falls pp. 208–224 Part Book VI. The Restoration Chapter I. The English Republic pp. 227–238 Chapter II. The Lord Protector pp. 239–252 Chapter III. The Restoration pp. 253–266 Chapter IV. The Merry Monarch pp. 267–282 Chapter V. The Popish Plot pp. 283–291 Chapter VI. Whig and Tory pp. 292–303 Chapter VII. The Catholic King pp. 304–313 Chapter VIII. The Revolution of 1688 pp. 314–326 Index pp. 327–345 ______________________________ The Second World War Volume III The Grand Alliance Winston Churchill`s monumental The Second World War, is a six volume account of the struggle between the Allied Powers in Europe against Germany and the Axis. Told by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, this book is also the story of one nation`s heroic role in the fight against tyranny. Having learned a lesson at Munich they would never forget, the British refused to make peace with Hitler, defying him even after France had fallen and it seemed as though the Nazis were unstoppable. The Grand Alliance describes the end of an extraordinary period in British military history in which Britain stood alone against Germany. Two crucial events brought an end of Britain`s isolation. First is Hitler`s decision to attack the Soviet Union, opening up a battle front in the East and forcing Stalin to look to the British for support. The second event is the bombing of Pearl Harbor. U.S. support had long been crucial to the British war effort, and Churchill documents his efforts to draw the Americans to aid, including correspondence with President Roosevelt. Moral of the Work pp. v–vi Acknowledgements pp. vii–viii Introduction pp. ix–xii Preface pp. xiii–xiv The Grand Alliance pp. xv–xviii Book I Germany Drives East Chapter I. The Desert and the Balkans pp. 3–19 Chapter II. The Widening War pp. 20–33 Chapter III. Blitz and Anti-Blitz pp. 34–49 Chapter IV. The Mediterranean War Chapter IV. The Mediterranean War pp. 50–69 Chapter V. Conquest of the Italian Empire pp. 70–82 Chapter VI. Decision to Aid Greece pp. 83–97 Chapter VII. The Battle of the Atlantic 1941 : The Western Approaches pp. 98–117 Chapter VIII. The Battle of the Atlantic 1941 : American Intervention pp. 118–137 Chapter IX. Yugoslavia pp. 138–155 Chapter X. The Japanese Envoy pp. 156–172 Chapter XI. The Desert Flank. Rommel. Tobruk pp. 173–192 Chapter XII. The Greek Campaign pp. 193–210 Chapter XIII. Tripoli and “Tiger” pp. 211–223 Chapter XIV. The Revolt in Iraq pp. 224–237 Chapter XV. Crete : The Advent pp. 238–251 Chapter XVI. Crete : The Battle pp. 252–269 Chapter XVII. The Fate of the “Bismarck” pp. 270–286 Chapter XVIII. Syria pp. 287–297 Chapter XIX. General Wavell’s Final Effort : “Battleaxe” pp. 298–314 Chapter XX. The Soviet Nemesis pp. 315–334 Book II War Comes To America Chapter XXI. Our Soviet Ally pp. 337–352 Chapter XXII. An African Pause. Defence of Tobruk pp. 353–372 Chapter XXIII. My Meeting With Roosevelt pp. 373–384 Chapter XXIV. The Atlantic Charter pp. 385–400 Chapter XXV. Aid to Russia pp. 401–422 Chapter XXVI. Persia and the Middle East : Summer and Autumn 1941 pp. 423–444 Chapter XXVII. The Mounting Strength of Britain : Autumn 1941 pp. 445–464 Chapter XXVIII. Closer Contacts with Russia : Autumn and Winter 1941 pp. 465–477 Chapter XXIX. The Path Ahead pp. 478–493 Chapter XXX. Operation “Crusader” Ashore, Aloft, and Afloat pp. 494–513 Chapter XXXI. Japan pp. 514–536 Chapter XXXII. Pearl Harbour! pp. 537–554 Chapter XXXIII. A Voyage Amid World War pp. 555–571 Chapter XXXIV. Proposed Plan and Sequence of the War pp. 572–586 Chapter XXXV. Washington and Ottawa pp. 587–603 Chapter XXXVI. Anglo-American Accords pp. 604–618 Chapter XXXVII. Return to Storm pp. 619–630 Appendices pp. 631–786 Index pp. 787–818 ____________________________________________ The Second World War Volume IV The Hinge of Fate Winston Churchill`s monumental The Second World War, is a six volume account of the struggle between the Allied Powers in Europe against Germany and the Axis. Told by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, this book is also the story of one nation`s heroic role in the fight against tyranny. Having learned a lesson at Munich they would never forget, the British refused to make peace with Hitler, defying him even after France had fallen and it seemed as though the Nazis were unstoppable. The Hinge of Fate is the dramatic account of the Allies` changing fortunes. In the first half of the book, Churchill describes the fearful period in which the Germans threaten to overwhelm the Red Army, Rommel dominates the war in the desert, and Singapore falls to the Japanese. In the span of just a few months, the Allies begin to turn the tide, achieving decisive victories at Midway and Guadalcanal, and repulsing the Germans at Stalingrad. As confidence builds, the Allies begin to gain ground against the Axis powers. Moral of the Work pp. v–vi Acknowledgements pp. vii–viii Introduction pp. ix–xii Preface pp. xiii–xiv Theme of the Volume pp. xv–xviii Book I The Onslaught of Japan Chapter I. Australasian Anxieties pp. 3–17 Chapter II. The Setback in the Desert pp. 18–31 Chapter III. Penalties in Malaya pp. 32–52 Chapter IV. A Vote of Confidence pp. 53–64 Chapter V. Cabinet Changes pp. 65–80 Chapter VI. The Fall of Singapore pp. 81–94 Chapter VII. The U-Boat Paradise pp. 95–117 Chapter VIII. The Loss of the Dutch East Indies pp. 118–133 Chapter IX. The Invasion of Burma pp. 134–151 Chapter X. Ceylon and the Bay of Bengal pp. 152–166 Chapter XI. The Shipping Stranglehold pp. 167–180 Chapter XII. India : The Cripps Mission pp. 181–196 Chapter XIII. Madagascar pp. 197–212 Chapter XIV. American Naval Victories : The Coral Sea And Midway Island pp. 213–227 Chapter XV. The Arctic Convoys 1942 pp. 228–247 Chapter XVI. The Offensive in the Æther pp. 248–259 Chapter XVII. Malta and the Desert pp. 260–279 Chapter XVIII. “Second Front Now!” April 1942 pp. 280–291 Chapter XIX. The Molotov Visit pp. 292–308 Chapter XX. Strategic Natural Selection pp. 309–318 Chapter XXI. Rommel Attacks pp. 319–335 Chapter XXII. My Second Visit to Washington pp. 336–350 Chapter XXIII. The Vote of Censure pp. 351–368 Book-II Africa Redeemed Chapter XXIV. The Eighth Army at Bay pp. 371–389 Chapter XXV. Decision for “Torch” pp. 390–407 Chapter XXVI. My Journey to Cairo. Changes in Command pp. 408–424 Chapter XXVII. Moscow : The First Meeting pp. 425–435 Chapter XXVIII. Moscow : A Relationship Established pp. 436–451 Chapter XXIX. Return to Cairo pp. 452–470 Chapter XXX. The Final Shaping of “Torch” pp. 471–492 Chapter XXXI. Suspense and Strain pp. 493–504 Chapter XXXII. Soviet “Thank You” pp. 505–525 Chapter XXXIII. The Battle of Alamein pp. 526–541 Chapter XXXIV. The Torch is Lit pp. 542–564 Chapter XXXV. The Darlan Episode pp. 565–580 Chapter XXXVI. Problems of Victory pp. 581–591 Chapter XXXVII. Our Need to Meet pp. 592–603 Chapter XXXVIII. The Casablanca Conference pp. 604–62 Chapter XXXIX. Adana and Tripoli pp. 623–642 Chapter XL. Home to Trouble pp. 643–662 Chapter XLI. Russia and the Western Allies pp. 663–681 Chapter XLII. Victory in Tunis pp. 682–698 Chapter XLIII. My Third Visit to Washington pp. 699–714 Chapter XLIV. Problems of War and Peace pp. 715–725 Chapter XLV. Italy : The Goal pp. 726–744 Back matter Appendices pp. 745–874 Index pp. 875–919 ________________________________________________________ The Second World War Volume V Moral of the Work pp. v–vi Acknowledgements pp. vii–viii Introduction pp. ix–xii Preface pp. xiii–xiv Theme of the Volume pp. xv–xvi Closing the Ring pp. xvii–xviii Book I Italy Won Chapter I. The Command of the Seas : Guadalcanal and New Guinea pp. 3–22 Chapter II. The Conquest of Sicily : July and August 1943 pp. 23–39 Chapter III. The Fall of Mussolini pp. 40–60 Chapter IV. Westward Ho! : Synthetic Harbours pp. 61–71 Chapter V. The Quebec Conference : “Quadrant” pp. 72–87 Chapter VI. Italy : The Armistice pp. 88–104 Chapter VII. The Invasion of Italy : At the White House Again pp. 105–123 Chapter VIII. The Battle of Salerno : A Homeward Voyage pp. 124–137 Chapter IX. A Spell at Home pp. 138–152 Chapter X. Tensions with General De Gaulle pp. 153–165 Chapter XI. The Broken Axis : Autumn 1943 pp. 166–179 Chapter XII. Island Prizes Lost pp. 180–200 Chapter XIII. Hitler’s “Secret Weapon” pp. 201–213 Chapter XIV. Deadlock on the Third Front pp. 214–227 Chapter XV. Arctic Convoys Again pp. 228–246 Chapter XVI. Foreign Secretaries’ Conference in Moscow pp. 247–266 Chapter XVII. Advent of the Triple Meeting the High Commands pp. 267–284 Book II Teheran To Rome Chapter XVIII. Cairo pp. 287–301 Chapter XIX. Teheran : The Opening pp. 302–316 Chapter XX. Conversations and Conferences pp. 317–330 Chapter XXI. Teheran : The Crux pp. 331–343 Chapter XXII. Teheran : Conclusions pp. 344–360 Chapter XXIII. Cairo Again. The High Command pp. 361–371 Chapter XXIV. In Carthage Ruins : Anzio pp. 372–387 Chapter XXV. At Marrakesh : Convalescence pp. 388–407 Chapter XXVI. Marshal Tito and Yugoslavia pp. 408–423 Chapter XXVII. The Anzio Stroke pp. 424–437 Chapter XXVIII. Italy : Cassino pp. 438–455 Chapter XXIX. The Mounting Air Offensive pp. 456–469 Chapter XXX. The Greek Torment pp. 470–488 Chapter XXXI. Burma And Beyond pp. 489–503 Chapter XXXII. Strategy Against Japan pp. 504–513 Chapter XXXIII. Preparations for “Overlord” pp. 514–527 Chapter XXXIV. Rome : May 11–June 9 pp. 528–541 Chapter XXXV. On The Eve pp. 542–558 Appendix B. List of Code-Names pp. 562–563 Appendix C. Prime Minister’s Personal Minutes and Telegrams : June 1943–May 1944 pp. 564–630 Appendix D. Monthly Totals of Shipping Losses, British, Allied, and Neutral by Enemy Action p. 631 Appendix E. Summary Of Order Of Battle, German And Italian Divisions, On September 8, 1943 pp. 632–634 Appendix F. The Release of the Mosleys Constitutional Issues pp. 635–637 Appendix G. Ministerial Appointments, June 1943–May 1944 pp. 638–640 Index pp. 641–673 ____________________________________ The Second World War Volume VI Triumph and Tragedy Moral of the Work pp. v–vi Acknowledgements pp. vii–viii Introduction pp. ix–xii Preface pp. xiii–xiv Theme of the Volume pp. xv–xvi Book I The Tide Of Victory Chapter I. D Day pp. 3–14 Chapter II. Normandy To Paris pp. 15–33 Chapter III. The Pilotless Bombardment pp. 34–49 Chapter IV. Attack on the South of France? pp. 50–62 Chapter V. Balkan Convulsions the Russian Victories pp. 63–74 Chapter VI. Italy and the Riviera Landing pp. 75–91 Chapter VII. Rome The Greek Problem pp. 92–103 Chapter VIII. Alexander’s Summer Offensive pp. 104–112 Chapter IX. The Martyrdom of Warsaw pp. 113–128 Chapter X. The Second Quebec Conference pp. 129–142 Chapter XI. Advance in Burma pp. 143–152 Chapter XII. The Battle of Leyte Gulf pp. 153–164 Chapter XIII. The Liberation of Western Europe pp. 165–179 Chapter XIV. Prelude to A Moscow Visit pp. 180–196 Chapter XV. October in Moscow pp. 197–212 Chapter XVI. Paris pp. 213–228 Chapter XVII. Counter-Stroke in the Ardennes pp. 229–246 Chapter XVIII. British Intervention in Greece pp. 247–266 Chapter XIX. Christmas at Athens pp. 267–284 Book II The Iron Curtain Chapter XX. Preparations for a New Conference pp. 287–301 Chapter XXI. Yalta : Plans for World Peace pp. 302–318 Chapter XXII. Russia and Poland : The Soviet Promise pp. 319–339 Chapter XXIII. Yalta Finale pp. 340–352 Chapter XXIV. Crossing the Rhine pp. 353–366 Chapter XXV. The Polish Dispute pp. 367–385 Chapter XXVI. Soviet Suspicions pp. 386–398 Chapter XXVII. Western Strategic Divergences pp. 399–411 Chapter XXVIII. The Climax : Roosevelt’s Death pp. 412–423 Chapter XXIX. Growing Friction with Russia pp. 424–439 Chapter XXX. The Final Advance pp. 440–453 Chapter XXXI. Alexander’s Victory in Italy pp. 454–462 Chapter XXXII. The German Surrender pp. 463–479 Chapter XXXIII. An Uneasy Interlude pp. 480–494 Chapter XXXIV. The Chasm Opens pp. 495–507 Chapter XXXV. The End of the Coalition pp. 508–519 Chapter XXXVI. A Fateful Decision pp. 520–531 Chapter XXXVII. The Defeat of Japan pp. 532–544 Chapter XXXVIII. Potsdam : The Atomic Bomb pp. 545–559 Chapter XXXIX. Potsdam : The Polish Frontiers pp. 560–577 Chapter XL. The end of My Account pp. 578–584 Back matter Appendices Appendix A. Appendix A p. 587 Appendix B. List of Code-Names p. 588 Appendix C. Prime Minister’s Directives, Personal Minutes, and Telegrams June 1944–July 1945 pp. 589–655 Appendix D. The Attack on the South of France pp. 656–664 Appendix E. Monthly Totals of Shipping Losses, British, Allied, and Neutral, by Enemy Action p. 665 Appendix F. Prime Minister’s Victory Broadcast, May 13, 1945 pp. 666–673 Appendix G. The Battle of the Atlantic Merchant Ships Sunk by U-Boat in the Atlantic p. 674 Appendix H. Ministerial Appointments, June 1944–May 1945 pp. 675–678 Index pp. 679–716 Nonfiction, History, WWII, Vinston Leonard Spenser Čerčil

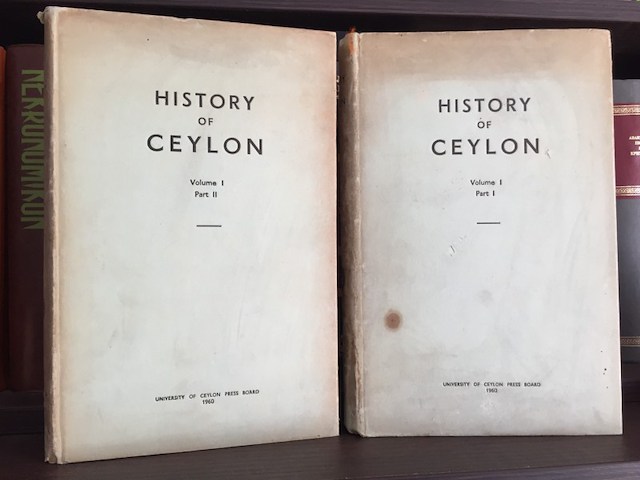

Lepo očuvano Kao na slikama Retko! 1960. University of Ceylon Press Board Istorija Cejlona / Šri Lanke Rare books The history of Sri Lanka is intertwined with the history of the broader Indian subcontinent and the surrounding regions, comprising the areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean. The early human remains found on the island of Sri Lanka date to about 38,000 years ago (Balangoda Man). The historical period begins roughly in the 3rd century, based on Pali chronicles like the Mahavamsa, Deepavamsa, and the Culavamsa. They describe the history since the arrival of Prince Vijaya from Northern India[1][2][3][4] The earliest documents of settlement in the Island are found in these chronicles. These chronicles cover the period since the establishment of the Kingdom of Tambapanni in the 6th century BCE by the earliest ancestors of the Sinhalese. The first Sri Lankan ruler of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, Pandukabhaya, is recorded for the 4th century BCE. Buddhism was introduced in the 3rd century BCE by Arhath Mahinda (son of the Indian emperor Ashoka). The island was divided into numerous kingdoms over the following centuries, intermittently (between CE 993–1077) united under Chola rule. Sri Lanka was ruled by 181 monarchs from the Anuradhapura to Kandy periods.[5][unreliable source?] From the 16th century, some coastal areas of the country were also controlled by the Portuguese, Dutch and British. Between 1597 and 1658, a substantial part of the island was under Portuguese rule. The Portuguese lost their possessions in Ceylon due to Dutch intervention in the Eighty Years` War. Following the Kandyan Wars, the island was united under British rule in 1815. Armed uprisings against the British took place in 1818 Uva Rebellion and 1848 Matale Rebellion. Independence was finally granted in 1948 but the country remained a Dominion of the British Empire until 1972. In 1972, Sri Lanka assumed the status of a Republic. A constitution was introduced in 1978 which made the Executive President the head of state. The Sri Lankan Civil War began in 1983, including Insurrections in 1971 and 1987, with the 25-year-long civil war ending in 2009. There was an attempted coup in 1962 against the government under Sirimavo Bandaranaike. Prehistory[edit] Main article: Prehistory of Sri Lanka Evidence of human colonization in Sri Lanka appears at the site of Balangoda. Balangoda Man arrived on the island about 125,000 years ago and has been identified as Mesolithic hunter-gatherers who lived in caves. Several of these caves, including the well-known Batadombalena and the Fa Hien Cave, have yielded many artifacts from these people, who are currently the first known inhabitants of the island. Balangoda Man probably created Horton Plains, in the central hills, by burning the trees in order to catch game. However, the discovery of oats and barley on the plains at about 15,000 BCE suggests that agriculture had already developed at this early date.[6] Several minute granite tools (about 4 centimetres in length), earthenware, remnants of charred timber, and clay burial pots date to the Mesolithic. Human remains dating to 6000 BCE have been discovered during recent excavations around a cave at Warana Raja Maha Vihara and in the Kalatuwawa area. Cinnamon is native to Sri Lanka and has been found in Ancient Egypt as early as 1500 BCE, suggesting early trade between Egypt and the island`s inhabitants. It is possible that Biblical Tarshish was located on the island. James Emerson Tennent identified Tarshish with Galle.[7] The protohistoric Early Iron Age appears to have established itself in South India by at least as early as 1200 BCE, if not earlier (Possehl 1990; Deraniyagala 1992:734). The earliest manifestation of this in Sri Lanka is radiocarbon-dated to c. 1000–800 BCE at Anuradhapura and Aligala shelter in Sigiriya (Deraniyagala 1992:709-29; Karunaratne and Adikari 1994:58; Mogren 1994:39; with the Anuradhapura dating corroborated by Coningham 1999). It is very likely that further investigations will push back the Sri Lankan lower boundary to match that of South India.[8] During the protohistoric period (1000-500 BCE) Sri Lanka was culturally united with southern India.,[9] and shared the same megalithic burials, pottery, iron technology, farming techniques and megalithic graffiti.[10][11] This cultural complex spread from southern India along with Dravidian clans such as the Velir, prior to the migration of Prakrit speakers.[12][13][10] Archaeological evidence for the beginnings of the Iron Age in Sri Lanka is found at Anuradhapura, where a large city–settlement was founded before 900 BCE. The settlement was about 15 hectares in 900 BCE, but by 700 BCE it had expanded to 50 hectares.[14] A similar site from the same period has also been discovered near Aligala in Sigiriya.[15] The hunter-gatherer people known as the Wanniyala-Aetto or Veddas, who still live in the central, Uva and north-eastern parts of the island, are probably direct descendants of the first inhabitants, Balangoda Man. They may have migrated to the island from the mainland around the time humans spread from Africa to the Indian subcontinent. Later Indo Aryan migrants developed a unique hydraulic civilization named Sinhala. Their Achievements include the construction of the largest reservoirs and dams of the ancient world as well as enormous pyramid-like stupa (dāgaba in Sinhala) architecture. This phase of Sri Lankan culture may have seen the introduction of early Buddhism.[16] Early history recorded in Buddhist scriptures refers to three visits by the Buddha to the island to see the Naga Kings, snakes that can take the form of a human at will.[17] The earliest surviving chronicles from the island, the Dipavamsa and the Mahavamsa, say that Yakkhas, Nagas, Rakkhas and Devas inhabited the island prior to the migration of Indo Aryans. Pre-Anuradhapura period (543–377 BCE)[edit] Main article: Early kingdoms period Indo-Aryan syncretism[edit] Main article: Prince Vijaya The Pali chronicles, the Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Thupavamsa and the Chulavamsa, as well as a large collection of stone inscriptions,[18] the Indian Epigraphical records, the Burmese versions of the chronicles etc., provide information on the history of Sri Lanka from about the 6th century BCE.[19] The Mahavamsa, written around 400 CE by the monk Mahanama, using the Deepavamsa, the Attakatha and other written sources available to him, correlates well with Indian histories of the period. Indeed, Emperor Ashoka`s reign is recorded in the Mahavamsa. The Mahavamsa account of the period prior to Asoka`s coronation, 218 years after the Buddha`s death, seems to be part legend. Proper historical records begin with the arrival of Vijaya and his 700 followers from Vanga. A detailed description of the dynastic accounts from Vijaya`s time is provided in the Mahavamsa.[20] H. W. Codrington puts it, `It is possible and even probable that Vijaya (`The Conqueror`) himself is a composite character combining in his person...two conquests` of ancient Sri Lanka. Vijaya is an Indian prince, the eldest son of King Sinhabahu (`Man with Lion arms`) and his sister Queen Sinhasivali. Both these Sinhalese leaders were born of a mythical union between a lion and a human princess. The Mahavamsa states that Vijaya landed on the same day as the death of the Buddha (See Geiger`s preface to Mahavamsa). The story of Vijaya and Kuveni (the local reigning queen) is reminiscent of Greek legend and may have a common source in ancient Proto-Indo-European folk tales. According to the Mahavamsa, Vijaya landed on Sri Lanka near Mahathitha (Manthota or Mannar[21]), and named[22] on the island of Tambaparni (`copper-colored sand`). This name is attested to in Ptolemy`s map of the ancient world. The Mahavamsa also describes the Buddha visiting Sri Lanka three times. Firstly, to stop a war between a Naga king and his son in law who were fighting over a ruby chair. It is said that on his last visit he left his foot mark on Siri Pada (`Adam`s Peak`). Tamirabharani is the old name for the second longest river in Sri Lanka (known as Malwatu Oya in Sinhala and Aruvi Aru in Tamil). This river was a main supply route connecting the capital, Anuradhapura, to Mahathitha (now Mannar). The waterway was used by Greek and Chinese ships traveling the southern Silk Route. Mahathir was an ancient port linking Sri Lanka to India and the Persian Gulf.[23] The present day Sinhalese are a mixture of the Indo Aryans and the Indigenous[24] The Sinhalese are recognized as a distinct ethnic group from other groups in neighboring south India based on the Indo-Aryan language, culture, Theravada Buddhism, genetics and the physical anthropology. Anuradhapura period (377 BCE–1017)[edit] Main articles: Anuradhapura period and Anuradhapura Kingdom Pandyan Kingdom coin depicting a temple between hill symbols and elephant, Pandyas, Sri Lanka, 1st century CE. In the early ages of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, the economy was based on farming and early settlements were mainly made near the rivers of the east, north central, and north east areas which had the water necessary for farming the whole year round. The king was the ruler of country and responsible for the law, the army, and being the protector of faith. Devanampiya Tissa (250–210 BCE) was Sinhalese and was friends with the King of the Maurya clan. His links with Emperor Asoka led to the introduction of Buddhism by Mahinda (son of Asoka) around 247 BCE. Sangamitta (sister of Mahinda) brought a Bodhi sapling via Jambukola (west of Kankesanthurai). This king`s reign was crucial to Theravada Buddhism and for Sri Lanka. The Mauryan-Sanskrit text Arthashastra referred to the pearls and gems of Sri Lanka. A kind of pearl, kauleya (Sanskrit: कौलेय) was referred in that text and also mentioned it collected from Mayurgrām of Sinhala. Pārsamudra(पारसमुद्र), a gem, was also being collected from Sinhala.[25] Ellalan (205–161 BCE) was a Tamil King who ruled `Pihiti Rata` (Sri Lanka north of the Mahaweli) after killing King Asela. During Ellalan`s time Kelani Tissa was a sub-king of Maya Rata (in the south-west) and Kavan Tissa was a regional sub-king of Ruhuna (in the south-east). Kavan Tissa built Tissa Maha Vihara, Dighavapi Tank and many shrines in Seruvila. Dutugemunu (161–137 BCE), the eldest son of King Kavan Tissa, at 25 years of age defeated the South Indian Tamil invader Elara (over 64 years of age) in single combat, described in the Mahavamsa. The Ruwanwelisaya, built by Dutugemunu, is a dagaba of pyramid-like proportions and was considered an engineering marvel.[citation needed] Pulahatta (or Pulahatha), the first of the Five Dravidians, was deposed by Bahiya. He in turn was deposed by Panaya Mara who was deposed by Pilaya Mara, murdered by Dathika in 88 BCE. Mara was deposed by Valagamba I (89–77 BCE) which ended Tamil rule. The Mahavihara Theravada Abhayagiri (`pro-Mahayana`) doctrinal disputes arose at this time. The Tripitaka was written in Pali at Aluvihara, Matale. Chora Naga (63–51 BCE), a Mahanagan, was poisoned by his consort Anula who became queen. Queen Anula (48–44 BCE), the widow of Chora Naga and of Kuda Tissa, was the first Queen of Lanka. She had many lovers who were poisoned by her and was killed by Kuttakanna Tissa. Vasabha (67–111 CE), named on the Vallipuram gold plate, fortified Anuradhapura and built eleven tanks as well as pronouncing many edicts. Gajabahu I (114–136) invaded the Chola kingdom and brought back captives as well as recovering the relic of the tooth of the Buddha. A Sangam Period classic, Manimekalai, attributes the origin of the first Pallava King from a liaison between the daughter of a Naga king of Manipallava named Pilli Valai (Pilivalai) with a Chola king, Killivalavan, out of which union was born a prince, who was lost in ship wreck and found with a twig (pallava) of Cephalandra Indica (Tondai) around his ankle and hence named Tondai-man. Another version states `Pallava` was born from the union of the Brahmin Ashvatthama with a Naga Princess also supposedly supported in the sixth verse of the Bahur plates which states `From Ashvatthama was born the king named Pallava`.[26] Sri Lankan imitations of 4th-century Roman coins, 4th to 8th centuries. Ambassador from Sri Lanka (獅子國 Shiziguo) to China (Liang dynasty), Wanghuitu (王会图), circa 650 CE There was intense Roman trade with the ancient Tamil country (present day Southern India) and Sri Lanka,[27] establishing trading settlements which remained long after the fall of the Western Roman Empire.[28] It was in the first century AD where Saint Thomas the Apostle introduced Sri Lanka`s first monotheistic religion, Christianity, according to a local Christian tradition[29] During the reign of Mahasena (274–301) the Theravada (Maha Vihara) was persecuted and the Mahayanan branch of Buddhism appeared. Later the King returned to the Maha Vihara. Pandu (429) was the first of seven Pandiyan rulers, ending with Pithya in 455. Dhatusena (459–477) `Kalaweva` and his son Kashyapa (477–495) built the famous Sigiriya rock palace where some 700 rock graffiti give a glimpse of ancient Sinhala. Decline Main article: Chola occupation of Anuradhapura In 993, when Raja Raja Chola sent a large Chola army which conquered the Anuradhapura Kingdom, in the north, and added it to the sovereignty of the Chola Empire.[30] The whole island was subsequently conquered and incorporated as a province of the vast Chola empire during the reign of his son Rajendra Chola.[31][32][33][34] Polonnaruwa period (1056–1232)[edit] Main articles: Polonnaruwa period and Kingdom of Polonnaruwa The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was the second major Sinhalese kingdom of Sri Lanka. It lasted from 1055 under Vijayabahu I to 1212 under the rule of Lilavati. The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa came into being after the Anuradhapura Kingdom was invaded by Chola forces under Rajaraja I and led to formation of the Kingdom of Ruhuna, where the Sinhalese Kings ruled during Chola occupation. Decline Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I invaded Sri Lanka in the 13th century and defeated Chandrabanu the usurper of the Jaffna Kingdom in northern Sri Lanka.[35] Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I forced Candrabhanu to submit to the Pandyan rule and to pay tributes to the Pandyan Dynasty. But later on when Candrabhanu became powerful enough he again invaded the Singhalese kingdom but he was defeated by the brother of Sadayavarman Sundara Pandyan I called Veera Pandyan I and Candrabhanu died.[35] Sri Lanka was invaded for the 3rd time by the Pandyan Dynasty under the leadership of Arya Cakravarti who established the Jaffna kingdom.[35] Transitional period (1232–1505)[edit] Ptolemic map of Ceylon (1482) Jaffna Kingdom[edit] Main article: Jaffna kingdom Also known as the Aryacakravarti dynasty, was a northern kingdom centred around the Jaffna Peninsula.[36] In 1247, the Malay kingdom of Tambralinga which was a vassal of the Srivijaya Empire led by their king Chandrabhanu[37] briefly invaded Sri Lanka especially the Jaffna Kingdom, from Insular Southeast Asia. They were then expelled by the South Indian Pandyan Dynasty.[38] However, this temporary invasion permanently introduced the presence of various Malayo-Polynesian merchant ethnic groups, from Sumatrans (Indonesia) to Lucoes (Philippines) into Sri Lanka.[39] Kingdom of Dambadeniya[edit] Main article: Kingdom of Dambadeniya After defeating Kalinga Magha, King Parakramabahu established his Kingdom in Dambadeniya. He built the Temple of The Sacred Tooth Relic in Dambadeniya. Kingdom of Gampola[edit] Main article: Kingdom of Gampola It was established by king Buwanekabahu IV, he is said to be the son of Sawulu Vijayabahu. During this time, a Muslim traveller and geographer named Ibn Battuta came to Sri Lanka and wrote a book about it. The Gadaladeniya Viharaya is the main building made in the Gampola Kingdom period. The Lankatilaka Viharaya is also a main building built in Gampola. Kingdom of Kotte[edit] Main article: Kingdom of Kotte After winning the battle, Parakramabahu VI sent an officer named Alagakkonar to check the new kingdom of Kotte. Kingdom of Sitawaka[edit] Main article: Kingdom of Sitawaka The kingdom of Sithawaka lasted for a short span of time during the Portuguese era. Vannimai[edit] Main article: Vanni Nadu Vannimai, also called Vanni Nadu, were feudal land divisions ruled by Vanniar chiefs south of the Jaffna peninsula in northern Sri Lanka. Pandara Vanniyan allied with the Kandy Nayakars led a rebellion against the British and Dutch colonial powers in Sri Lanka in 1802. He was able to liberate Mullaitivu and other parts of northern Vanni from Dutch rule. In 1803, Pandara Vanniyan was defeated by the British and Vanni came under British rule.[40] Crisis of the Sixteenth Century (1505–1594)[edit] Portuguese intervention[edit] Main articles: Portuguese Ceylon and Sinhalese–Portuguese War A Portuguese (later Dutch) fort in Batticaloa, Eastern Province built in the 16th century. The first Europeans to visit Sri Lanka in modern times were the Portuguese: Lourenço de Almeida arrived in 1505 and found that the island, divided into seven warring kingdoms, was unable to fend off intruders. The Portuguese founded a fort at the port city of Colombo in 1517 and gradually extended their control over the coastal areas. In 1592, the Sinhalese moved their capital to the inland city of Kandy, a location more secure against attack from invaders. Intermittent warfare continued through the 16th century. Many lowland Sinhalese converted to Christianity due to missionary campaigns by the Portuguese while the coastal Moors were religiously persecuted and forced to retreat to the Central highlands. The Buddhist majority disliked the Portuguese occupation and its influences, welcoming any power who might rescue them. When the Dutch captain Joris van Spilbergen landed in 1602, the king of Kandy appealed to him for help.[41] Dutch intervention[edit] Main article: Dutch Ceylon Rajasinghe II, the king of Kandy, made a treaty with the Dutch in 1638 to get rid of the Portuguese who ruled most of the coastal areas of the island. The main conditions of the treaty were that the Dutch were to hand over the coastal areas they had captured to the Kandyan king in return for a Dutch trade monopoly over the island. The agreement was breached by both parties. The Dutch captured Colombo in 1656 and the last Portuguese strongholds near Jaffnapatnam in 1658. By 1660 they controlled the whole island except the land-locked kingdom of Kandy. The Dutch (Protestants) persecuted the Catholics and the remaining Portuguese settlers but left Buddhists, Hindus and Muslims alone. The Dutch levied far heavier taxes on the people than the Portuguese had done.[41] Kandyan period (1594–1815)[edit] Main article: Kingdom of Kandy On the top: illustration from Delineatio characterum quorundam incognitorum, quos in insula Ceylano spectandos praebet tumulus quidam sepulchralis published in Acta Eruditorum, 1733 After the invasion of the Portuguese, Konappu Bandara (King Vimaladharmasuriya) intelligently won the battle and became the first king of the kingdom of Kandy. He built The Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic. The monarch ended with the death of the last king, Sri Vikrama Rajasinha in 1832.[42] Colonial Sri Lanka (1815–1948)[edit] Main articles: History of British Ceylon and British Ceylon Late 19th-century German map of Ceylon. During the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might deliver Sri Lanka to the French, occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called Ceylon) with little difficulty in 1796. In 1802, the Treaty of Amiens formally ceded the Dutch part of the island to Britain and it became a crown colony. In 1803, the British invaded the Kingdom of Kandy in the first Kandyan War, but were repulsed. In 1815 Kandy was annexed in the second Kandyan War, finally ending Sri Lankan independence. Following the suppression of the Uva Rebellion the Kandyan peasantry were stripped of their lands by the Crown Lands (Encroachments) Ordinance No. 12 of 1840 (sometimes called the Crown Lands Ordinance or the Waste Lands Ordinance),[43] a modern enclosure movement, and reduced to penury. The British found that the uplands of Sri Lanka were very suitable for coffee, tea and rubber cultivation. By the mid-19th century, Ceylon tea had become a staple of the British market bringing great wealth to a small number of European tea planters. The planters imported large numbers of Tamil workers as indentured labourers from south India to work the estates, who soon made up 10% of the island`s population.[44] The British colonial administration favoured the semi-European Burghers, certain high-caste Sinhalese and the Tamils who were mainly concentrated to the north of the country. Nevertheless, the British also introduced democratic elements to Sri Lanka for the first time in its history and the Burghers were given degree of self-government as early as 1833. It was not until 1909 that constitutional development began, with a partly elected assembly, and not until 1920 that elected members outnumbered official appointees. Universal suffrage was introduced in 1931 over the protests of the Sinhalese, Tamil and Burgher elite who objected to the common people being allowed to vote.[44] Sorting tea in Ceylon in the 1880s Independence movement[edit] Main article: Sri Lankan independence movement Ceylon National Congress (CNC) was founded to agitate for greater autonomy, although the party was soon split along ethnic and caste lines. Historian K. M. de Silva has stated that the refusal of the Ceylon Tamils to accept minority status is one of the main causes of the break up of the Ceylon National congress. The CNC did not seek independence (or `Swaraj`). What may be called the independence movement broke into two streams: the `constitutionalists`, who sought independence by gradual modification of the status of Ceylon; and the more radical groups associated with the Colombo Youth League, Labour movement of Goonasinghe, and the Jaffna Youth Congress. These organizations were the first to raise the cry of `Swaraj` (`outright independence`) following the Indian example when Jawaharlal Nehru, Sarojini Naidu and other Indian leaders visited Ceylon in 1926.[45] The efforts of the constitutionalists led to the arrival of the Donoughmore Commission reforms in 1931 and the Soulbury Commission recommendations, which essentially upheld the 1944 draft constitution of the Board of ministers headed by D. S. Senanayake.[45] The Marxist Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), which grew out of the Youth Leagues in 1935, made the demand for outright independence a cornerstone of their policy.[46] Its deputies in the State Council, N.M. Perera and Philip Gunawardena, were aided in this struggle by other less radical members like Colvin R. De Silva, Leslie Goonewardene, Vivienne Goonewardene, Edmund Samarkody and Natesa Iyer. They also demanded the replacement of English as the official language by Sinhala and Tamil. The Marxist groups were a tiny minority and yet their movement was viewed with great interest by the British administration. The ineffective attempts to rouse the public against the British Raj in revolt would have led to certain bloodshed and a delay in independence. British state papers released in the 1950s show that the Marxist movement had a very negative impact on the policy makers at the Colonial office.[44] The Soulbury Commission was the most important result of the agitation for constitutional reform in the 1930s. The Tamil organization was by then led by G. G. Ponnambalam, who had rejected the `Ceylonese identity`.[47] Ponnamblam had declared himself a `proud Dravidian` and proclaimed an independent identity for the Tamils. He attacked the Sinhalese and criticized their historical chronicle known as the Mahavamsa. The first Sinhalese-Tamil riot came in 1939.[45][48] Ponnambalam opposed universal franchise, supported the caste system, and claimed that the protection of minority rights requires that minorities (35% of the population in 1931) having an equal number of seats in parliament to that of the Sinhalese (65% of the population). This `50-50` or `balanced representation` policy became the hall mark of Tamil politics of the time. Ponnambalam also accused the British of having established colonization in `traditional Tamil areas`, and having favoured the Buddhists by the Buddhist temporalities act. The Soulbury Commission rejected the submissions by Ponnambalam and even criticized what they described as their unacceptable communal character. Sinhalese writers pointed to the large immigration of Tamils to the southern urban centres, especially after the opening of the Jaffna-Colombo railway. Meanwhile, Senanayake, Baron Jayatilleke, Oliver Gunatilleke and others lobbied the Soulbury Commission without confronting them officially. The unofficial submissions contained what was to later become the draft constitution of 1944.[45] The close collaboration of the D. S. Senanayake government with the war-time British administration led to the support of Lord Louis Mountbatten. His dispatches and a telegram to the Colonial office supporting Independence for Ceylon have been cited by historians as having helped the Senanayake government to secure the independence of Sri Lanka. The shrewd cooperation with the British as well as diverting the needs of the war market to Ceylonese markets as a supply point, managed by Oliver Goonatilleke, also led to a very favourable fiscal situation for the newly independent government.[44] The Second World War[edit] Main article: Ceylon in World War II Sri Lanka was a front-line British base against the Japanese during World War II. Sri Lankan opposition to the war led by the Marxist organizations and the leaders of the LSSP pro-independence group were arrested by the Colonial authorities. On 5 April 1942, the Indian Ocean raid saw the Japanese Navy bomb Colombo. The Japanese attack led to the flight of Indian merchants, dominant in the Colombo commercial sector, which removed a major political problem facing the Senanayake government.[45] Marxist leaders also escaped to India where they participated in the independence struggle there. The movement in Ceylon was minuscule, limited to the English-educated intelligentsia and trade unions, mainly in the urban centres. These groups were led by Robert Gunawardena, Philip`s brother. In stark contrast to this `heroic` but ineffective approach to the war, the Senanayake government took advantage to further its rapport with the commanding elite. Ceylon became crucial to the British Empire in the war, with Lord Louis Mountbatten using Colombo as his headquarters for the Eastern Theatre. Oliver Goonatilleka successfully exploited the markets for the country`s rubber and other agricultural products to replenish the treasury. Nonetheless, the Sinhalese continued to push for independence and the Sinhalese sovereignty, using the opportunities offered by the war, pushed to establish a special relationship with Britain.[44] Meanwhile, the Marxists, identifying the war as an imperialist sideshow and desiring a proletarian revolution, chose a path of agitation disproportionate to their negligible combat strength and diametrically opposed to the `constitutionalist` approach of Senanayake and other ethnic Sinhalese leaders. A small garrison on the Cocos Islands manned by Ceylonese mutinied against British rule. It has been claimed that the LSSP had some hand in the action, though this is far from clear. Three of the participants were the only British colony subjects to be shot for mutiny during World War II.[49] Two members of the Governing Party, Junius Richard Jayawardene and Dudley Senanayake, held discussions with the Japanese to collaborate in fighting the British. Sri Lankans in Singapore and Malaysia formed the `Lanka Regiment` of the anti-British Indian National Army.[44] The constitutionalists led by D. S. Senanayake succeeded in winning independence. The Soulbury constitution was essentially what Senanayake`s board of ministers had drafted in 1944. The promise of Dominion status and independence itself had been given by the Colonial Office. Independence[edit] The Sinhalese leader Don Stephen Senanayake left the CNC on the issue of independence, disagreeing with the revised aim of `the achieving of freedom`, although his real reasons were more subtle.[50] He subsequently formed the United National Party (UNP) in 1946,[51] when a new constitution was agreed on, based on the behind-the-curtain lobbying of the Soulbury commission. At the elections of 1947, the UNP won a minority of seats in parliament, but cobbled together a coalition with the Sinhala Maha Sabha party of Solomon Bandaranaike and the Tamil Congress of G.G. Ponnambalam. The successful inclusions of the Tamil-communalist leader Ponnambalam, and his Sinhalese counterpart Bandaranaike were a remarkable political balancing act by Senanayake. The vacuum in Tamil Nationalist politics, created by Ponnamblam`s transition to a moderate, opened the field for the Tamil Arasu Kachchi (`Federal party`), a Tamil sovereignty party led by S. J. V. Chelvanaykam who was the lawyer son of a Christian minister.[44] Tags: sri lanka hinduizam budizam cedomil veljačić kulture istoka