Pratite promene cene putem maila

- Da bi dobijali obaveštenja o promeni cene potrebno je da kliknete Prati oglas dugme koje se nalazi na dnu svakog oglasa i unesete Vašu mail adresu.

1-6 od 6 rezultata

Broj oglasa

Prikaz

1-6 od 6

1-6 od 6 rezultata

Prikaz

Prati pretragu "15-36"

Vi se opustite, Gogi će Vas obavestiti kad pronađe nove oglase za tražene ključne reči.

Gogi će vas obavestiti kada pronađe nove oglase.

Režim promene aktivan!

Upravo ste u režimu promene sačuvane pretrage za frazu .

Možete da promenite frazu ili filtere i sačuvate trenutno stanje

Izdavač: Caxton Editions, London Povez: tvrd Broj strana: 96 Ilustrovano. Format: 19,5 x 25,5 cm Veoma dobro očuvana. Practiced for centuries in the Middle East, India and Africa, body art was linked with the traditions of marriage, birth and death. Body art has again become popular and the trend has been spurred on by the stars of music and media. Over 15 projects are pictured and explained using traditional powdered and premixed henna paste in harmony with coloured henna and water-based Indian body paints. There are also 50 design ideas to choose from - patterns and ideas from ancient, Celtic, Mexican, North American, Indian and South Pacific cultures. This practical guide will stimulate your imagination and inspire you to explore the inexhaustible art of body art. (K-36)

Русская живопись XIX века Moskva, Rusija 1962. Tvrd povez, ruski jezik, bogato ilustrovano, veliki format (27×35 cm), 12 strana + 64 lista sa reprodukcijama. Knjiga je veoma dobro očuvana. T1 Sadržaj: 1. О. А. КИПРЕНСКИЙ (1782—1836) : Портрет А. С. Пушкина. 1827 г. 2 . О. А. КИПРЕНСКИЙ (1782—1836) : Автопортрет. 1809 г. 3. В. А. ТРОПИНИН (1776—1857): Голова мальчика (Портрет сына художника). Окo 1818 г. 4 . А. Г. ВЕНЕЦИАНОВ (1780—1847) : На пашне. Весна 5 . А. Г. ВЕНЕЦИАНОВ (1780—1847) : Спящии пастушок. 1824 г. Государсгденный Русскай музей 6 . СИЛЬВ. Ф. ЩЕДРИН (1791—1830) : На острове Капри. 1826 г. 7 . К. П. БРЮЛЛОВ (1799—1852) : Последнии день Помпеи. 1830—1833 гг. 8 . К. П. БРЮЛЛОВ (1799—1852) : Портрет Ю. П. Самоиловои с воспитанницеи на маскараде. 1839—1840 гг. 9 . К. П. БРЮЛЛОВ (1799—1852): Автопортрет. 1848 г. 10 . А. А. ИВАНОВ (1806—1858) : Явление Христа народу 1837—1857 г. 11 . А. А. ИВАНОВ (1806—1858): Голова раба. Этюд 12 . А. А. ИВАНОВ (1806—1858) : Обнаженныи мальчик. Сидящий на Драпировке 13 . А. Л. ИВAНОВ (1806—1858) : Аппиева дорога при закате солнца. 1845 г. 14 . П. А. ФЕДОТОВ (1815—1852) : Сватовство майорa, 1848 г. 15 . П. А. ФЕДОТОВ (1815—1852) : «Анкор, еще анкор!» 16 . В. Г. ПЕРОВ : (1833—1882) : Сельский крестныи ход на Пасхе. 1861 г. 17 . В. Г. ПЕРОВ (1833—1882) : Последнии кабак у заставы. 1868 г. 18 . В. Г. ПЕРОВ (1833—1882) : Портрет Ф. М. Достоевского. 1872 г. 19 . И. Н. КРАМСКОЙ (1837—1887) : Автопортрет. 1867 г. 20 . И. Н. КРАМСКОЙ (1837—1887): Портрет Л. Н. Толстого. 1873 г. 21. Н. Н. ГЕ (1831—1894): Тайная вечеря. 1863 г. 22. Н. Н. ГЕ (1831—1894): Петр I допрашивает царевича алексея петровича в Петергофе. 1871 г. 23. А. К. САВРАСОВ (1830—1897): Грачи прилетели. 1871 г. 24. Ф. А. ВАСИЛЬЕВ (1850—1873): Оттепель. 1871 г. 25. В. В. ВЕРЕЩАГИН (1842—1904): Смертельно раненныи. 1873 г. 26. В. В. ВЕРЕЩАГИН (1842—1904): Шипка-шеиново. Скобелев под Шипкой. 1877—1878 г. 27. И. К. АЙВАЗОВСКИИ (1817—1900): Черное море. 1881 г. 28. И. И. ШИШКИН (1832—1898): Рожь. 1878 г. 29. И. И. ШИШКИН ( 1832— 1898): В лесу мордвиновой. 1891 г. 30. К. Л. СЛВИЦКИИ (1844—1905): Встреча иконы. 1878 г. 31. В. М. МАКСИМОВ (1844—1911): Приход колдуна на крестьянскую свадьбу. 1875 г. 32. В. Е. МАКОВСКИЙ(1846—1920): Свидание. 1883 г. 33. В. Е. МАКОВСКИЙ (1846—1920): Вечеринка. 1875—1897 гг. 34. Н. А. ЯРОШЕНКО (1846—1898): Кочегар. 1878 г. 35. Н. А. ЯРОШЕНКО (1846—1898): Курсистка. 1883 г. 36. И. Е. РЕПИН (1844—1930): Бурлаки на Волге. 1870—1873 гг. 37. И. Е. РЕПИН (1844—1930): Протодиакон. 1877 г. 38. И. Е. РЕПИН (1844—1930): Портрет М. П. Мусоргского. 1881 г. 39. И. Е. РЕПИН (1844— 1930): Крестныи ход В Курской губерний. 1880—1883 гг. 40. И. Е. РЕПИН (1844—1930): Не ждали. 1884—1888 гг. 41. В. И. СУРИКОВ (1848—1916): Утро стрелецкои казни. 1881 г. 42. В. И. СУРИКОВ (1848—1916): Меншиков в Березове. 1883 г. 43. В. И. СУРИКОВ (1848—1916): Боярыня морозова. 1887 г. 44. В. И. СУРИКОВ (1848—1916): Олова боярыни морозовой. Этюд. 1886 45. В. И. СУРИКОВ (1848—1916): Покорение Сибири Ермаком. 1895 г. 46. В. М. ВАСНЕЦОВ (1848—1926): Аленушка. 1881 г. 47. В. М. ВАСНЕЦОВ (1848—1926): Богатыри. 1881—1898 гг. 48. А. И. КУИНДЖИ (1842—1910): Березовая роща. 1879 г. 49. В. Д. ПОЛЕНОВ (1844—1927): Московский дворик. 1878 г. 50. И. И. ЛЕВИТАН (1860—1900): Март. 1895 г. 51. И. И. ЛЕВИТАН (1860—1900): Золотая осень. 1895 г. 52. И. И. ЛЕВИТАН (1860—1900): Летнии вечер. 1900 г. 53 . М. А. ВРУБЕЛЬ (1856—1910) : Демон. 1890 г. 54 . М. А. ВРУБЕЛЬ (1856—1910) : Пан. 1899 г. 55 . М. А. ВРУБЕЛЬ (1856—1910): К ночи. 1900 г. 56 . С. В. ИВАНОВ (1864—1910) : В дороге. Смерть переселенца. 1889 г. 57 . К. А. КОРОВИН (1861—1939): У Балкона. Испанки Леонора И Ампара. 1886 г. 58 . Н. А. КАСАТКИН (1859—1930) : Углекопы. Смена. 1895 г. 59 . А. Е. АРХИПОВ (1862—1930) : По реке Оке. 1890 г. 60. А. П. РЯБУШКИН (1861—1904) : Свадебныи поезд в Москве XVII столетия. 1901 г. г 61. Ф. А. МАЛЯВИН (1869—1939): Крестьянка в красном платье 62. В. А. СЕРОВ (1865—1911): Девушка, освещенная солнцем. 1888 г. 63. В. А. СЕРОВ (1865—1911): Октябрь. Домотканово. 1895 г. 64. В. А. СЕРОВ (1865—1911): Портрет М. Н. Ермоловой. 1905 г.

- I Read Where I Am: Exploring New Information Cultures Valiz/Graphic Design Museum, Breda, 2011 264 str. meki povez stanje: dobro – Visionary texts about the future of reading and the status of the word – With contributions by 82 invited authors: journalists, designers, researchers, politicians, philosophers and many others I Read Where I Am contains visionary texts about the future of reading and the status of the word. We read anytime and anywhere. We read of screens, we read out on the streets, we read in the office but less and less we read a book at home on the couch. We are, or are becoming, a different type of reader. How will we grapple with compressed narratives and the fluid bombardment of text? What are the dialectics between image and word? How will our information machines generate new reading cultures? Can reading become a live, mobile social experience? To answer all these (and other) questions, I Read Where I Am displays 82 diverse observations, inspirations and critical notes by journalists, designers, researchers, politicians, philosophers and many others. Authors: Arie Altena, Henk Blanken, Andrew Blauvelt, Erwin Blom, James Bridle, Max Bruinsma, Anne Burdick, Vito Campanelli, Catalogtree, Florian Cramer, Sean Dockray, Paulien Dresscher, Dunny & Raby, Sven Ehmann, Martin Ferro-Thomsen, Jeff Gomez & 66 other authors Editors: Mieke Gerritzen, Geert Lovink, Minke Kampman Design: LUST When Guy Debord identified the image consumerism of “the society of the spectacle” in the 1960s, he could not have forecast that language would threaten to eclipse the image in the medium of personal technology, creating a world of ubiquitous legibility. Today, we read anytime and anywhere, on screens of all sizes; we read not only newspaper articles, but also databases, online archives, search engine results and navigational structures. We read while out on the street, at home or in the office, with a complete library to hand--but less and less we read a book at home on the couch. In other words, we are, or are becoming, a different kind of reader. I Read Where I Am contains visionary texts about the future of reading and the status of the word in the digital age from designers, philosophers, journalists and politicians, looking at both sides of the argument for printed and digital reading matter. A collection of short reflections on the future of reading, including those from Ellen Lupton, James Bridle, Erik Spiekermann, and N. Katharine Hayles. Independently, none of the essays are especially compelling; but collectively, they reveal our shared unease (the loss of print, increased distraction, information overload) and make clear that none of us has any idea what the future will bring. Which, of course, is what makes the future interesting. Unfortunately, the typesetting (words are colored in different shades of gray depending on their frequency of use) is interesting in theory but incredibly annoying in practice; perhaps it is an attempt to prove that a stubborn reader will suffer through even the worst of reading experiences in order to get at the words? Index Contents Indexes Index on First 140 Characters of Essay |p16 Index of Word Frequency |p22 Index on Related Subjects |p178 82 essays 01|p50 Gathering Up Characters Arie Altena 02|p51 Better Stories Henk Blanken 03|p53 From Books to Texts Andrew Blauvelt 04|p54 I Read More Than Ever Erwin Blom 05|p56 Encoded Experiences James Bridle 06|p57 Watching, Formerly Reading Max Bruinsma 07|p60 If Words, Then Reading Anne Burdick 08|p60 Flowing Together Vito Campanelli 09|p62 Highway Drugs and Data Visualization Catalogtree 10|p64 The Revenge of the Gutenberg Galaxy Florian Cramer 11|p66 Where Do You Read? Sean Dockray 12|p67 Pancake Paulien Dresscher 13|p69 Between Reality and the Impossible: Revisited Dunne & Raby 14|p70 Weapons of Mass Distraction Sven Ehmann 15|p73 Reading Beyond Words Martin Ferro-Thomsen 16|p74 We Left Home; Why Shouldn`t Ideas? Jeff Gomez 17|p75 Delectation Denise Gonzales Crisp 18|p78 Welcome to the Digital Age. What Changed? Alexander Griekspoor 19|p77 Non-linear Publishing Hendrik-Jan Grievink 20|p78 Subtitling Ger Groot 21|p80 Ambient Scholarship Gary Hall 22|p82 Set the Text Free: Balancing Textual Agency Between Humans and Machines John Haltiwanger 23|p83 Educate Well, Read Better N. Katherine Hayles 24|p85 Reading the Picture Toon Horsten 25|p85 Apples and Cabbages Minke Kampman 26|p86 How Will We Read? Lynn Kaplanian-Buller 27|p88 Screening Kevin Kelly 28|p90 I Don`t Read on My Bike Joost Kircz 29|p91 Reading As Event Matthew Kirschenbaum 30|p91 Reading the Network Tanja Koning 31|p93 Nearby and Global in Its Impact Steffen Konrath 32|p95 The Interface of the Graphic Novel Erin La Cour 33|p97 Minimal and Maximal Reading Rudi Laermans 34|p99 Reading Apart Together Warren Lee 35|p100 Unexpected Ways Jannah Loontjens 36|p101 Consume Without a Screen Alessandro Ludovico 37|p103 The Networked Culture Machine Peter Lunenfeld 38|104 From Noun to Verb Ellen Lupton 39|106 The Role of the Hardware Anne Mangen 40|p107 From Reading to Pattern Recognition Lev Manovich 41|p109 Reading `For the Sake of It` Luna Maurer 42|p111 The Matrix: Three Subject- ive and Intuitively Selected Pointers for Building Blocks for The Script in Which We Live Geert Mul 43|p113 Horses Are Fine So Are Books Arjen Mulder 44|p115 Shapes Caroline NeveJan 45|117 Achievement Unlocked! David B. Nieborg 46|p118 U-turn Kali Nikitas 47|p119 The Epitaph or Writing Beyond the Grave Henk Oosterling 48|p121 Jumping Frames David Ottina 49|p123 Pictures and Words Peter Pontiac 50|p125 The Grammar of Images Ine Poppe 51|p127 The Many Readers in My Body Emilie Randoe 52|p129 Arrangements Bernhard Rieder 53|p130 Desecration of Reading Paul Rutten 54|p131 Epi-phany Plea for a Counter- culture of Un-reading and Un-writing Johan Sanctorum 55|p133 Savouring Thoughts Louise Sandhaus 56|p134 The Stutter in Reading (Call for a New Quality of Reading) Niels Schrader 57|p135 I Read in the Mind Ray Siemens 58|p136 Full Circle Karin Spaink 59|p137 Books Erik Spiekermann 60|p138 The New Orality and the Empty House Matthew Stadler 61|p140 Letter en geest I Letter and Spirit F. Starik 62|p141 Social Reading Bob Stein 63|p144 Is the Role of Libraries in Reading Innovation Fading? Michael Stephens & Jan Klerk 64|p146 Slow Reading Carolyn Strauss 65|p147 Cyclops iPad Dick Tuinder 66|p148 Context Is King; Content Is Queen Lian van de Wiel 67|p150 Reading Becomes Looking Bregtje van der Haak 68|p152 The Library Is As Large As One Half of the Brain Eis van der Plas 69|p155 Classic Canon Rick van der Ploeg 70|p156 Content Economies Daniel van der Velden 71|p157 Do Images Also Argue? Adriaan van der Weel 72|p158 Read Me First Erwin van der Zande 73|p160 Designing a New Stratification of Information Rene van Engelenburg 74|p162 Dancing Words Francisco van Jole 75|p163 Books Are Bullets in the Battle for the Minds of Men Peter van Lindonk 76|p165 Reading Surroundings Koert van Mensvoort 77|p166 Reading with Electronic Blinkers Tjebbe van Tijen 78|p168 Better Tools Dirk van Weelden 79|p170 E-Stone Jack van Wijk 80|p172 Mushrooms and Truffles Astrid Vorstermans 81|p173 Book It McKenzie Wark 82|p174 Danger: Contains Books Simon Worthington Nonfiction, 9078088559

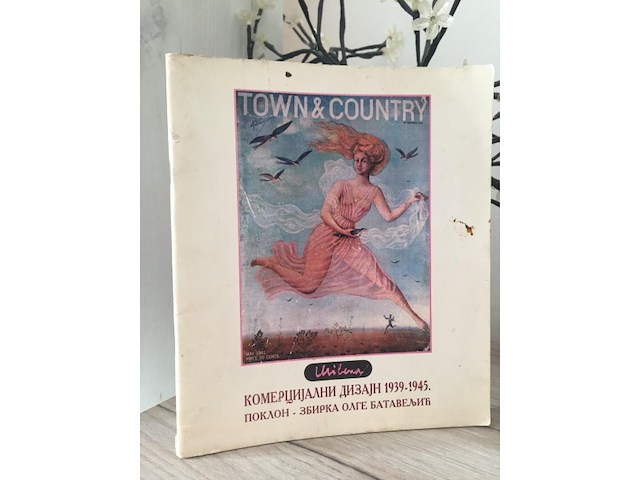

Kao na slikama Retko u ponudi Milena Pavlović-Barili (Požarevac, 5. novembar 1909 — Njujork, 6. mart 1945) bila je srpska slikarka.[1] Neki izvori je opisuju kao jednu od najinteresantnijih ličnosti umetničke Evrope između dva svetska rata.[2] Od 1932. godine živi i radi u Parizu, a od 1939. u SAD, gde i umire u 36. godini života. Redovno je učestvovala na izložbama paviljona Cvijeta Zuzorić i umetničke grupe Lada[3] ali je i pored toga, usled dugog boravka i smrti u inostranstvu, bila u Srbiji gotovo zaboravljena. Svoja dela uspešno je izlagala i na brojnim samostalnim i grupnim izložbama širom Evrope, a kasnije i u Americi, gde sarađuje u modnom časopisu Vog. Njeno delo je domaćoj javnosti otkriveno tek 50-ih godina 20. veka, zahvaljujući slikaru, likovnom kritičaru, teoretičaru i istoričaru umetnosti Miodragu Protiću, koji je njeno delo otkrio srpskoj (i jugoslovenskoj) javnosti 50-ih godina 20. veka.[4] Sa Radojicom Živanovićem Noem Milena Pavlović-Barili je jedini afirmisani predstavnik nadrealizma u srpskom slikarstvu.[5] Poreklo[uredi | uredi izvor] Glavni članci: Danica Pavlović-Barili i Bruno Barili Milenina čukunbaba Sava Karađorđević, Karađorđeva najstarija ćerka . Milena kao mala sedi u krilu bake Bose, otac Bruno, majka Danica i deda Stojan Milena Pavlović-Barili rođena je 1909. godine u Požarevcu, u rodnoj kući svoje majke, Danice Pavlović-Barili. Danica je (po ženskoj liniji) bila praunuka Save Karađorđević, udate Ristić, najstarije Karađorđeve ćerke.[6] Studirala je muziku, klavir i pevanje na konzervatorijumu u Minhenu gde je, u novembru 1905. godine, upoznala Mileninog oca Bruna Barilija.[7] Milenin otac Bruno Barili bio je poznati italijanski kompozitor, muzički kritičar, pesnik i putopisac.[8] U Srbiji je uglavnom poznat kao otac Milene Pavlović-Barili, ali i kao ratni dopisnik iz Srbije tokom Prvog balkanskog i Prvog svetskog rata[9] i pisac memoarskog proznog dela Srpski ratovi.[10] Čuvena parmanska porodica Barili[11] dala je veliki broj umetnika - slikara, pesnika, muzičara[12] i glumaca.[13] Milenin deda Čekrope Barili takođe je bio slikar.[a][15] Milenin deda po majci, Stojan Stojančić Pavlović, bio je predsednik požarevačke opštine, narodni poslanik Napredne stranke, trgovac duvanom i rentijer.[12] Milenina baka Bosiljka godinama je bila predsednica Kola srpskih sestara u Požarevcu.[16] Drugi Milenin deda sa majčine strane bio je Živko Pavlović, poznatiji kao Moler iz Požarevca, koji je krajem 19. veka oslikao unutrašnjost crkve Svetog Arhangela Mihaila u Ramu pored Velikog Gradišta.[17] Detinjstvo[uredi | uredi izvor] Milena sa majkom Danicom, 1911. Već samo srpsko-italijansko poreklo bilo je razlog da najranije detinjstvo Milena provede na relaciji Srbija – Italija,[8] a na to je najviše uticala činjenica da su njeni roditelji živeli razdvojeno, verovatno zbog neslaganja karaktera, da bi se 1923. godine i pravno razveli, mada nikada nisu prekinuli kontakt. Naime odmah po venčanju, 8. januara 1909. godine u pravoslavnoj crkvi u Požarevcu, mladi bračni par odlazi u Parmu, kod Brunove porodice[18] ali, sudeći po zapisima iz Daničinih memoara ona se ubrzo vraća u Srbiju,[b] te je tako Milena Pavlović-Barili rođena u rodnoj kući svoje majke, u Požarevcu. Ipak, već posle šest nedelja, majka i baka Bosiljka odlaze sa Milenom u Rim da bi se nakon osam meseci, zbog Milenine bolesti, vratile nazad u Požarevac.[20][21] Ovakav način života i neprestana putovanja pratiće Milenu sve do odlaska u Sjedinjene Američke Države. Milenin život i rad takođe je obeležila i bolest srca, koja joj je ustanovljena verovatno već u osmom mesecu života[22] i koja će je pratiti do kraja života i biti uzrok njene prerane smrti. Opravdano se pretpostavlja da je upravo bolest imala velikog uticaja na Milenin život i rad i terala mladu umetnicu da aktivno proživi svaki, takoreći poklonjeni trenutak života. Ovako ozbiljni zdravstveni problemi sigurno su u velikoj meri uzrok tako silovitog rada i zaista velikog broja dela koje je iza sebe ostavila.[8] Odnos sa majkom[uredi | uredi izvor] Jedan od prvih majčinih portreta, Milena sa majkom, naslikan 1926. prema staroj fotografiji. Izrađen je u tehnici ulje na kartonu, 47×50,5 cm. Signatura na poleđini (ćirilica): Kopija fotografije iz 1914. mama sa mnom, Milena; (vlasnik: Galerija Milene Pavlović-Barili, Požarevac, Srbija) Portret oca, Bruna Barilija, naslikan 1938. godine. Izrađen je u tehnici ulje na platnu, 41×33 cm (vlasnik: Galerija Milene Pavlović-Barili, Požarevac, Srbija) Iako je završila studije muzike na čuvenim evropskim konzervatorijumima, Danica Pavlović-Barili se nikada kasnije u životu nije aktivno bavila muzikom. Posle Mileninog rođenja ceo svoj život i svu svoju energiju posvetila odgajanju, školovanju, usavršavanju i lečenju ćerke, a nakon Milenine prerane smrti čuvanju uspomene na nju. Bila je tip žene za koju je odnos sa detetom važniji od odnosa sa muškarcem, spremna da za svoje potomstvo podnese izuzetne žrtve, ali i kasnije kada to dete odraste, utiče na njegov život, životne odluke i odnose s drugim ljudima. Preuzela je odlučujuću ulogu u Mileninom vaspitanju i odgajanju i skoro sigurno kasnije predstavljala dominantnu ličnost u njenom životu. Olivera Janković, autorka jedne od mnogih biografija Milene Pavlović-Barili, Danicu poredi sa velikim majkama iz mitologije, Demetrom ili Leto. Postoji veoma malo sećanja savremenika na Milenu Pavlović-Barili, ali prema onima koja su sačuvana „Milena je bila mila i privlačna, volela je da se oblači ekstravagantno i privlači pažnju, ali je bio dovoljan samo jedan pogled njene majke da se njeno ponašanje promeni”. Sa druge strane i Milena je prema majci imala zaštitnički stav. O tome svedoči zaista veliki broj Daničinih portreta koje je uradila, a na kojima ističe majčinu suzdržanost, otmenost i lepotu, kao stvarne činjenice, ali i kao statusni simbol. Osim kratkog perioda službovanja na Dvoru, Danica je sa ćerkom živela u Požarevcu, u roditeljskoj kući sa majkom i bratom, obeležena za to vreme neprijatnom etiketom razvedene žene. Posle smrti njenog oca Stojana Pavlovića 1920. godine porodica je naglo osiromašila i lagodan život na koji su navikli više nije bio moguć. U takvim uslovima Milena se prema majci ponašala ne samo kao ćerka, već i kao prijateljica, zaštitnica i utešiteljka.[7] Školovanje[uredi | uredi izvor] Već u najranijem detinjstvu, čim je progovorila, majka Milenu uči uporedo srpskom i italijanskom jeziku. U tom najranijem periodu pokazuje i veliki interes za crtanje. U to vreme u Srbiji traju Balkanski ratovi, pa Bruno, tada ratni izveštač iz Srbije, obilazi porodicu. U kratkom periodu mira, do izbijanja Prvog svetskog rata, Milena sa majkom obilazi Italiju. Pred izbijanje rata vraćaju se u Požarevac, gde ostaju do 1. jula 1915, kada odlaze u Italiju, a kasnije i u Francusku.[21] Godine 1916. Milena u Bergamu završava prvi razred osnovne škole. Drugi razred pohađa na Italijansko-engleskom institutu u Rimu (Istituto Italiano Inglese), a zatim sa majkom odlazi u Nicu, gde uči i francuski jezik.[23] Po završetku rata Milena se sa majkom, preko Krfa i Dubrovnika, vraća u Srbiju i privatno, za godinu dana, u Požarevcu završava treći i četvrti razred osnovne škole i upisuje gimnaziju. Milena je u to vreme već imala puno crteža za koje su, prema rečima njene majke, mnogi u Italiji, pa čak i čuveni, tada jugoslovenski vajar Ivan Meštrović, govorili da su sjajni. [21] Tokom drugog razreda gimnazije majka odvodi Milenu na putovanje po Evropi. Odlaze u Linc, gde pohađa Majerovu školu u kojoj je prvi put ozbiljnije primećen njen talenat,[20] a zatim u Grac, gde u ženskom manastiru uči nemački jezik. Po povratku u Požarevac 1922. godine Milena privatno završava drugi razred gimnazije i pripremni tečaj za upis u Umetničku školu u Beogradu, na koju biva primljena, prema rečima njene majke, kao „vunderkind” uprkos činjenici da ima tek 12 godina. Umetničku školu pohađa uporedo sa nižom gimnazijom.[24] U Umetničkoj školi predavali su joj poznati srpski likovni pedagozi i umetnici tog vremena: Beta Vukanović, Ljubomir Ivanović i Dragoslav Stojanović. Za vreme Mileninog školovanja u Beogradu Danica Pavlović primljena je u službu na Dvor kralja Aleksandra Karađorđevića, prvo kao činovnik u Kancelariji kraljevskih ordena, zatim kao nadzornica, gde između ostalog ima zadatak i da podučava srpskom jeziku kraljicu Mariju.[21] Godine 1925. Milena je privatno završila četvrti razred u Drugoj ženskoj gimnaziji u Beogradu, a naredne, 1926. diplomirala na Umetničkoj školi u Beogradu i stekla pravo na položaj nastavnika.[23] Priredila je prvu samostalnu izložbu u Novinarskom klubu u Beogradu. Izlagala je stotinak slika, akvarela, pastela i crteža.[3] Na prolećnoj izložbi Umetničke škole izlagala je zajedno sa školskim drugovima Đorđem Andrejevićem Kunom i Lazarom Ličenoskim.[11] Dnevni list Politika u svom izveštaju sa tog događaja ističe pored ostalih i radove g-đice Milene Pavlović-Barili „koja ima i nekoliko izvrsnih pastela”.[20] Studije slikarstva[uredi | uredi izvor] Zgrada minhenske slikarske akademije U jesen 1926. godine Milena odlazi sa majkom u Minhen. Posle kraćeg vremena provedenog u privatnim školama Blocherer bosshardt i Knirr-Shule na pripremama, upisuje minhensku slikarsku akademiju Akademie der bildenden Künste. Primljena je u klasu profesora Huga fon Habermena, da bi od drugog semestra studira kod mnogo požnatijeg profesora, Franca fon Štuka.[23] Fon Štuk je, prema majčinim rečima, napravio tri izuzetka od svojih pravila da bi je primio: bila je devojka, bila je premlada i bila je prekobrojna. Stari profesor se toliko vezao za svoju mladu i talentovanu učenicu da se sa njom dopisivao sve do svoje smrti.[21] Uprkos tome Milena se na Akademiji osećala sputana da kroz slikarstvo izrazi svoju ličnost. U jednom intervjuu 1937. godine ona ovako opisuje vreme provedeno u minhenskoj Akademiji: „Patnja koju u meni izaziva slikarstvo neopisiva je... Prvi veliki napor koji sam morala učiniti da... zaista intimno osetim svoju umetnost bio je napor da se oslobodim konvencionalnih formi koje su mi nametnule godine akademskih studija u Nemačkoj u jednom gluvom i reakcionarnom ambijentu”. Zato sredinom 1928. napušta Minhen i Akademiju i sa majkom odlazi u Pariz.[25] Može se reći da odlazak u Minhen predstavlja početak Mileninog nomadskog načina života.[8] Nomadski život[uredi | uredi izvor] Autoportret (1938), ulje na platnu, 64×52,5 cm, bez signature (vlasnik Galerija Milene Pavlović-Barili, Požarevac, Srbija) Kompozicija (1938) Biografija Milene Pavlović-Barili bitno se razlikuje od biografskog modela većine srpskih umetnika koji su stvarali između dva rata. Ona nije imala stalno zaposlenje, pa samim tim ni stalni izvor prihoda. Nije imala ni finansijsku pomoć mecene ili države, a njena porodica, iako nekada dobrostojeća, nije mogla da joj obezbedi bezbrižan život, s obzirom da je veliki deo novca odlazio i na njeno lečenje, a porodica posle smrti Mileninog dede Stojana Pavlovića prilično osiromašila.[7] Zato je ona rano počela da zarađuje za život. Godine 1928. sa majkom se vraća u rodni Požarevac, gde pokušava da nađe zaposlenje kao profesor crtanja. Ipak, uprkos svestranom obrazovanju i već priznatom talentu, njena molba biva odbijena, kako u Požarevcu, tako i u Štipu, Tetovu i Velesu, sa klasičnim obrazloženjem da „nema budžetskih sredstava”. U martu 1930. preko Italije i Francuske odlazi sa majkom na proputovanje po Španiji, gde obilazi Granadu, Barselonu, Sevilju, Valensiju i Kordobu. Španija je bila Milenina velika čežnja, što pokazuju i mnogi radovi koji su prethodili ovom putovanju (Prvi osmeh, Serenada, Toreador). Iz Španije odlazi u Pariz, a zatim u London, gde ostaje do 1932. godine. Posle Londona vraća se u Pariz gde živi do 1939. godine. Jesen i zimu 1938/39. provodi u Oslu, a u avgustu 1939. odlazi u Njujork, gde ostaje sve do svoje prerane smrti, 6. marta 1945. Ovakav kosmopolitski život svakako je imao veliki uticaj kako na Milenin rad tako i na njenu ličnost u celini. Na svojim putovanjima obilazi galerije i muzeje, prisustvuje brojnim izložbama, a na mnogima i sama izlagala. Svo to ostavilo je trag na njenim slikama.[8] Život i rad u Americi[uredi | uredi izvor] Naslovne strane `Voga` i jedna od dvadesetak haljina koje je Milena kreirala čuvaju se u Galeriji u njenoj rodnoj kući u Požarevcu Hot pink with cool gray (Toplo ružičasto sa hladnim sivim), ilustracija objavljena u Vogu 15. januara 1940. godine Godine 1939, 18. avgusta, Milena kreće iz Avra brodom „De Grasse” za Njujork, gde stiže 27. avgusta.[23] Već u martu sledeće godine samostalno izlaže u njujorškoj galeriji Julien Levy Gallery koja se pominje kao značajna referenca u izlagačkoj delatnosti mnogih priznatih umetnika, posebno nadrealista. Brojni prikazi u dnevnoj štampi i umetničkim publikacijama ukazuju na dobar prijem u njujorškoj umetničkoj javnosti. Procenivši da se zbog nadolazećeg rata neće skoro vratiti u Evropu, Milena počinje da traži izvor stalnih prihoda. Ohrabrena majčinim sugestijama, sa kojom održava redovan kontakt putem čestih i iscrpnih pisama (i čiji uticaj nije ništa manji zbog udaljenosti), ona počinje da radi portrete ljudi iz visokog društva. Ovaj angažman joj, pored finansijske satisfakcije, svakako pomaže da se snađe u novoj sredini i uspostavi neophodna poznanstva i veze. Ubrzo dobija i angažman u elitnom modnom časopisu Vog, gde njene ilustracije postižu zapažen uspeh i ubrzo u istom časopisu dobija i ugovor o stalnoj saradnji. Zahvaljujući tom uspehu ona proširuje svoj rad na komercijalnom dizajnu kroz saradnju sa mnogim žurnalima i časopisima (Harpers bazar, Taun end kantri...), radeći naslovne strane, dizajn odeće i obuće i reklame za tekstilnu industriju. Radila je i neku vrstu inscenacija za artikle najvećih modnih kuća u Njujorku, dizajn za parfem i kolonjsku vodu firme Meri Danhil, kozmetičke preparate kuće Revlon, kao i ilustracije ženske odeće i obuće za različite modne kreatore.[26] Prve godine u Americi bile su posebno teške za Milenu, naročito 1940. kada je, sudeći po prepisci, već u januaru imala srčane tegobe, a verovatno i srčani udar. Ovoliki komercijalni angažman previše je okupira, pa sledeću izložbu, samostalnu, otvara tek početkom 1943. godine u Njujorku, a zatim u maju i u Vašingtonu. Prilikom otvaranja vašingtonske izložbe upoznaje mladog oficira avijacije[11] Roberta Tomasa Astora Goselina (Robert Thomass Astor Gosselin). Milena se već 24. decembra 1943. godine udaje za dvanaest godina mlađeg Roberta, ali on ubrzo biva otpušten iz vojske, pa mladi par, zbog finansijskih problema, prelazi da živi na njegovom imanju. U leto 1944. godine odlaze na bračno putovanje, na kome Milena doživljava nesreću. Tokom jednog izleta pada s konja i zadobija ozbiljnu povredu kičme, zbog koje je prinuđena da ostane u gipsanom koritu nekoliko meseci.[27] Po izlasku iz bolnice, radi bržeg oporavka, mladi par seli se u Monte Kasino, mali grad u blizini Njujorka. Tu Milena upoznaje Đankarla Menotija (Gian Carlo Mennoti), slavnog kompozitora čija su dela u to vreme bila najpopularnija među probirljivom njujorškom publikom. Saznavši za njene finansijske probleme, Menoti joj nudi angažman na izradi kostima za balet Sebastijan, za koji je komponovao muziku. Milena oberučke prihvata ovu ponudu i još uvek neoporavljena počinje rad na kostimima. Balet postiže veliki uspeh, a sa njim i Milena. Časopis La Art tada piše: „Izuzetno efektni Milenini kostimi u duhu italijanskog baroka, koji podsećaju na nadrealistički stil ove umetnice izvanredni su kada sugerišu sjaj Venecije, gospodarice mora u vremenu opadanja njene moći...”. Zahvaljujući ovom uspehu Milena potpisuje ugovor o saradnji na izradi kostima za balet San letnje noći.[28] Milenine ruke (posmrtni odlivak u bronzi), paleta i tube sa bojom. Milenini poslednji dani i smrt[uredi | uredi izvor] U martu 1945. godine Milena i Robert sele se u svoj novi stan u Njujorku. Milenin uspeh postaje izvestan i izgleda kao da finansijski problemi ostaju daleko iza nje. Rat u Evropi se završava i ona se nada skorom ponovnom susretu sa roditeljima. Iz pisma koje je uputio majci Danici Robert Goselin, a u kome detaljno opisuje događaje, može se zaključiti koliko je Milenina smrt bila iznenadna i neočekivana: uveče 5. marta mladi bračni par odlazi u restoran da proslavi preseljenje. Vraćaju se kući dosta kasno, odlaze na počinak, a Milena ostavlja sobarici poruku da je ujutru probudi u 10 sati... U svom stanu u Njujorku Milena je umrla od srčanog udara 6. marta 1945. godine. U lekarskom nalazu napisano je da je višemesečni život u gipsanom koritu oslabio njeno srce, tako da bi ostala invalid i da je prebolela udar. Đankarlo Menoti, pišući kasnije o Mileninoj smrti, navodi da niko, pa čak ni njen muž, nije znao da joj je srce u tako lošem stanju.[27][8] Milena Pavlović-Barili je kremirana, a urna sa njenim posmrtnim ostacima sahranjena je na groblju blizu Njujorka. Robert Goselin je 1947. urnu lično odneo Brunu Bariliju i ona je 5. avgusta 1949. godine položena u grobnicu br. 774 na rimskom nekatoličkom groblju Cimitero cacattolico deglinstranieri (Testaccio).[23][v] U istu grobnicu kasnije su, po sopstvenoj želji, sahranjeni i njen roditelji: otac Bruno, 1952. i majka Danica 1965. godine. [29][18][30] Slikarski rad[uredi | uredi izvor] Zgrada Kraljevske umetničke škole u Beogradu, u kojoj se danas nalazi Fakultet primenjenih umetnosti Univerziteta umetnosti u Beogradu Madona, 1929. Interes za likovnu umetnost Milena Pavlović-Barili pokazala je veoma rano. Svoju prvu slikarsku kompoziciju, egzotične cvetove, nacrtala je već sa pet godina, a potom i kompoziciju sa jarićima obučenim u haljinice. Veruje se da su ovi crteži bili neka vrsta kompenzacije za druženje sa vršnjacima, koje joj je bilo uskraćeno zbog bolešljivosti ili drugih zabrana.[31] Već na samom početku profesionalnog stvaralaštva kod Milene se zapaža okrenutost ka ljudskom liku i portretu, dok su pejzaž, mrtva priroda i slični motivi u njenom opusu retki i uglavnom ih koristi kao pozadinu u kompozicijama u kojima dominira ljudska figura. U njenom opusu posebno je veliki broj portreta i autoportreta, koje slika od najranijih dana (brojne portrete majke, ujaka, babe, kolega sa klase, svojih filmskih idola...) pa do njujorškog perioda, kada u jednom periodu na taj način zarađuje za život. Kroz celokupno njeno slikarstvo prožimaju se bajkovitost, usamljenost i seta.[8] Njeni radovi odaju naklonost prema dekorativnosti i ilustraciji.[4] Već posle prve samostalne izložbe u Parizu, u proleće 1932. godine, njen slikarski talenat je zapažen u umetničkim krugovima Pariza. De Kiriko u njoj prepoznaje pravac mekog metafizičkog slikarstva, a Žan Kasu joj piše predgovor za katalog. Njenim slikama očarani su Andre Lot, Pol Valeri i mnogi drugi.[11] U Parizu je došlo do naglog osamostaljenja Milanine umetnosti, za šta je verovatno najzaslužniji novi, prisan odnos sa ocem. Njegova umetnička interesovanja i krug boema, umetnika i intelektualaca u kom se kretao i u koji je uveo i Milenu morali su predstavljati veliko ohrabrenje i podsticaj naglo otkrivenoj samostalnosti likovnog izraza mlade umetnice. Bez njegove pomoći verovatno ne bi bila moguća ni izuzetno velika izlagačka aktivnost tokom prvih godina života u Parizu.[32] Slikarstvo Milene Pavlović-Barili prolazilo je kroz nekoliko faza u kojima nema jasnih i naglih rezova, ali ima bitnih razlika. Klasifikaciju Mileninog slikarstva dao je Miodrag B. Protić, najveći poznavalac i teoretičar Mileninog umetničkog rada:[2] Umetnost Milene Pavlović-Barili u Srbiji, odnosno u Kraljevini Jugoslaviji nije nailazila na razumevanje, što se može videti iz njenih pisama u kojima majci opisuje svoje utiske sa jedne izložbe:[32] oktobar 1932. ... Iz poslanstva mi još niko nije došao. Cela ljubaznost se svodi na to da su mi još pre dva meseca stavili do znanja da preko njih može, preko Ministarstva spoljnih poslova da mi se pošalje od kuće koliko hoću novaca. ... Pitala sam i molila da mi poslanstvo kupi jednu sliku, tim pre što ih ja ničim nisam do sada uznemiravala... On (službenik) reče da bi bilo dobro da se stanjim i da potražim mesto u Južnoj Srbiji, i da je kupovina lična ministrova stvar, itd, itd. I da će videti Presbiro, itd. (Puno lepih reči). Poslepodne je došao iz poslanstva samo on sa ženom. ... Ni jedan novinar jugoslovenski nije došao. ... Akademizam (1922‒1931) Umetnička škola, Beograd (1922‒1926) Umetnička akademija, Minhen (1926‒1928) Prvi znaci: sinteza akademizma, secesija filmskog plakata, Beograd (1928‒1930) Postnadrealizam (1932‒1945) Magički relacionizam (linearni period), Pariz, Rim (1932‒1936) Magički relacionizam („renesansni period), Firenca, Venecija, Pariz - „Nove snage” (1936‒1939) Magički verizam, Njujork (1939‒1945) U odnosu na sve druge naše slikare toga vremena Milena Pavlović-Barili bila je izvan i iznad glavnih razvojnih tokova jugoslovenskog slikarstva, ukalupljenog u stereotip evropske umetnosti tridesetih godina, posebno Pariske škole.[2] Usled dugog boravka i smrti u inostranstvu, u Srbiji i Jugoslaviji bila je gotovo zaboravljena, sve dok njeno delo domaćoj javnosti nije otkrio Miodrag B. Protić 50-ih godina 20. veka, tekstom u NIN-u (17. oktobar 1954), da bi već u novembru sledeće godine usledila izložba njenih radova u Galeriji ULUS-a.[4] Milena Pavlović-Barili za života je uradila preko 300 radova, kao i veliki broj skica i crteža. Njena dela čuvaju se u Galeriji Milene Pavlović-Barili u Požarevcu, Muzeju savremene umetnosti i Narodnom muzeju u Beogradu, kao i u mnogim svetskim muzejima i privatnim zbirkama. Milenina dela su, u organizaciji Galerije Milene Pavlović-Barili iz Požarevca, izlagana u mnogim evropskim gradovima: Briselu, Parmi, Parizu, Bukureštu, Bratislavi, Pragu, Brnu, Skoplju i Zagrebu[33] kao i u mnogim gradovima u Srbiji među kojima je izložba održana u Galeriji Srpske akademije nauka i umetnosti u Beogradu, kao i izložbe u Somboru, Sremskoj Mitrovici i Gornjem Milanovcu.[34] Najvažnije izložbe[uredi | uredi izvor] Umetnički paviljon „Cvijeta Zuzorić” u Beogradu Prvu samostalnu izložbu Milena je otvorila u 16. decembra 1928. godine u Novinarskom domu na Obilićevom vencu u Beogradu[23], gde se predstavila sa 120 radova nastalih tokom školovanja u Beogradu i Minhenu. Kritika je ovaj prvi Milenin korak u svet umetnosti dočekala blagonaklono, predviđajući joj „sjajnu umetničku budućnost”. O njenom radu pozitivne kritike daju, između ostalih likovni kritičar Sreten Stojanović i pesnik Gustav Krklec.[25] Već januara 1929. godine otvara svoju samostalnu izložbu i u Požarevcu, a nešto kasnije postaje članica Lade i učestvuje na Prvoj prolećnoj i Drugoj jesenjoj izložbi jugoslovenskih umetnika u Paviljonu „Cvijeta Zuzorić” u Beogradu, zajedno sa našim najpoznatijim slikarima i vajarima - Jovanom Bijelićem, Lazarom Ličenoskim, Vasom Pomorišcem, Ristom Stijovićem, Ivanom Radovićem, Milanom Konjovićem, Marinom Tartaljom, Tomom Rosandićem.[35] Tokom jednogodišnjeg boravka u Londonu, 27. februara 1931. otvara samostalnu izložbu u londonskoj Bloomsbery Gallery. Godine 1932. izleže na 15. izložbi Lade, otvorenoj 15. marta u Beogradu. Iste godine u proleće samostalno izlaže u Galerie Jeune Europe u Parizu. Na jesen iste godine u Rimu, u Galleria d`Arte. Do 1939. godine, kada odlazi u Njujork, Milena izlaže na brojnim samostalnim i grupnim izložbama širom Evrope: Sala d`Arte de `La nazione` (sa Marijom Sinjoreli i Adrianom Pinkerele, Firenca, april 1933), XII éme Salon des Tuileries (Pariz, 1934), II Quadriennale d`arte Nazionale (Rim, februar 1935), Galleriadella Cometa (samostalna izložba, Rim, januar 1937), Quatre chemins (samostalna izložba, Pariz, januar 1938), Samostalna izložba u organizaciji ambasade Kraljevine Jugoslavije u Tirani (mart 1938) Galerie Billiet (sa grupom Nouvelle generation, Pariz, april 1938), Galerie Pitoresque (izložba novog nadrealizma, Pariz 1939) i Galerie Beruhcim Jeune (sa jugoslovenskim umetnicima iz Pariza, Pariz i Hag 1939). U avgustu 1939. godine Milena odlazi u Njujork i već u martu 1940. samostalno izlaže u njujorškoj galeriji Julien Levy Gallery. Komercijalni angažman u Americi previše je okupira, pa sledeću izložbu, samostalnu, otvara tek u zimu 1943. godine u United Yugoslav Relief Fund u Njujorku, a u maju se izložba seli u Corcoran Gallery u Vašingtonu. Prerana smrt zaustavila je dalji uzlet ove jedinstvene umetnice.[8] Književni rad[uredi | uredi izvor] Prve pesme, začuđujuće zrele za svoj uzrast, Milena je pisala još kao sasvim mala devojčica. Milutin Tasić navodi jednu koju je napisala kao sedmogodišnja devojčica, mada nije poznato da li svoju ili odnekud zapamćenu.[24] Roma sabato, 12. novembre 1916. Milena Kad sunce svanjiva i ptičice pevaju onda, onda je leto al ja neću da ga dočekam neću da dočekam na ovom svetu! Ovaj svet sanak samo sanak lep.[36] Bista Milene Pavlović Barili u Galeriji u Požarevcu, rad vajara Nebojše Mitrića (1965) U tekstu pod naslovom „Milenini nervi“, objavljenom 1943. godine u Njuzviku pominje se da je umetnica, posle 11 godina neprekidnog slikanja, počela da pati od akutne estetske prezasićenosti, zbog čega dve godine nije slikala već je pisala poeziju, kao i da je patila od „užasne” nostalgije praćene čestom promenom raspoloženja. Ovo se verovatno odnosi na period 1934/1935. godine, kada je nastao sasvim neznatan broj umetničkih radova. U ovom periodu napisala je 60 pesama na četiri jezika: 17 na italijanskom, 14 na španskom, 7 na francuskom i 22 na srpskom. Godine 1934. objavljuje svoju poeziju u italijanskom časopisu Kvadrivio (Quadrivio). U pesništvu je, kao i u slikarstvu, ostala dosledna sebi, pa se i kroz poeziju prožimaju bajkovitost, usamljenost i seta.[37] Prevodi pesama Milene Pavlović-Barili prvi put su objavljeni 1966. godine u monografiji Miodraga B. Protića Milena Pavlović Barili, život i delo.[38], a kasnije u katalogu retrospektivne izložbe 1979. i u Protićevoj monografiji iz 1990.[8] Milenine pesme objavljene su prvi put kao zbirka 1998. godine pod naslovom Poezija[39] i u ovoj zbirci su prvi put objavljeni prevodi pesama sa španskog jezika.[40] Kulturološki uticaj[uredi | uredi izvor] U beogradskom naselju Rakovica, Petrovaradinu, Požarevcu, kao i u Lazarevcu i Velikom Gradištu postoje ulice koja nosi ime Milene Pavlović-Barili.[41][42][43][44][45] U Beogradu jedna osnovna škola (opština Palilula, naselje Višnjička banja)[46] i jedna privatna gimnazija (opština Stari grad)[47] takođe nose ime „Milena Pavlović-Barili”. U čast Milene Pavlović-Barili Pošta Jugoslavije, a kasnije Srbije nekoliko puta je objavljivala poštanske marke čiji su motivi njene slike. Marka sa mileninim likom izašla je na dan Mileninog rođendana 2015. godine i u Kanadi.[48] Poštanska marka Jugoslavije iz 1977. - Autoportret (1938), ulje na platnu Poštanska marka Jugoslavije iz 1977. - Autoportret (1938), ulje na platnu Poštanska marka Jugoslavije iz 1993 - Kompozicija (1938), ulje na platnu Poštanska marka Jugoslavije iz 1993 - Kompozicija (1938), ulje na platnu Poštanska marka Srbije iz 2009. - Autoportret sa velom (1939), ulje na platnu Poštanska marka Srbije iz 2009. - Autoportret sa velom (1939), ulje na platnu Galerija Milene Pavlović-Barili[uredi | uredi izvor] U znak zahvalnosti i sećanja na našu čuvenu, rano preminulu slikarku u Požarevcu je, 24. juna 1962. godine pod krovom preuređene stare porodične kuće Pavlovića, otvorena Galerija Milene Pavlović-Barili. Inicijator i glavni darodavac je slikarkina majka Danica Pavlović-Barili, koja je odlučila da imovinu koju je nasledila od svojih roditelja i umetnički fond svoje preminule kćeri daruje srpskom narodu i da se ova zaostavština sačuva kao celina.[49] Glavni članak: Galerija Milene Pavlović-Barili u Požarevcu Milenina rodna kuća, sada Galerija Milenina rodna kuća, sada Galerija Spomen ploča koju je postavila Danica Pavlović-Barili Spomen ploča koju je postavila Danica Pavlović-Barili Spomen soba u Galeriji Spomen soba u Galeriji Milenine igračke i odeća iz detinjstva Milenine igračke i odeća iz detinjstva Milenine lične stvari Milenine lične stvari Milenin slikarski pribor Milenin slikarski pribor Umetnička dela o Mileni i njenom radu[uredi | uredi izvor] O likovnom i književnom opusu napisane su mnoge monografije i kritike, od kojih su najvažnije navedene u literaturi. Pored toga njen fascinantni život i rad bili su inspiracija mnogim autorima u različitim oblastima književnog i umetničkog stvaralaštva: Romani[uredi | uredi izvor] Mitrović, Mirjana (1990). Autoportret sa Milenom : roman. Beograd: BIGZ. ISBN 978-86-13-00420-2.COBISS.SR 274956 Stojanović, Slobodan (1997). Devojka sa lampom, 1936. Požarevac: Centar za kulturu. ISBN 978-86-82973-03-4.COBISS.SR 129704711 Biografska građa[uredi | uredi izvor] Dimitrijević, Kosta; Stojanović-Guleski, Smilja (1971). Ključevi snova slikarstva : život, delo, pisma, pesme Milene Pavlović-Barili. Kruševac: Bagdala.COBISS.SR 15793415 Graovac, Živoslavka (1999). Ogledalo duše : Milena Pavlović Barilli. Beograd: Prosveta. ISBN 978-86-07-01204-6.COBISS.SR 151631879 Mazzola, Adele (2009). Aquae passeris : o Mileni Pavlović Barili. Beograd: HISPERIAedu. ISBN 978-86-7956-021-6. Приступљено 7. 12. 2017.COBISS.SR 158071308 Stanković, Radmila (2009). Milenin usud. Beograd: Globosino. ISBN 978-86-7900-035-4.COBISS.SR 170036492 Performans Milena ZeVu; „Milena` - Omaž srpskoj umetnici Mileni Pavlović Barili, mart 2019, Dom Jevrema Grujića Beograd, Srbija Drame[uredi | uredi izvor] Milena Barili - žena sa velom i lepezom (autor: Slobodan Marković)[50] Krila od olova (autor: Sanja Domazet, režija: Stevan Bodroža, premijera: Beogradsko dramsko pozorište, 2004)[51] Mesec u plamenu (autor: Sanja Domazet, režija: Stevan Sablić, premijera: Beogradsko dramsko pozorište, 10. decembar 2009)[52] Filmovi i TV emisije[uredi | uredi izvor] Milena Pavlović-Barili (Kratki dokumentarni film, 1962, režija: Ljubiša Jocić, scenario: Miodrag Protić)[53] Devojka sa lampom (TV film, 1992, režija: Miloš Radivojević, scenario: Slobodan Stojanović, glavna uloga: Maja Sabljić)[54] Milena Pavlović-Barili ponovo u Parizu (TV emisija, 2002, autor emisije: Vjera Vuković)[55][56] Autoportret s belom mačkom (Animirani film, 2009, scenario: Mirjana Bjelogrlić, crtež: Bojana Dimitrovski, animacija: Bogdan Vuković)[57][56] Milena (2011, scenario i režija: Čarna Radoičić)[58] Napomene[uredi | uredi izvor] ^ Galerija Milene Pavlović-Barili u Požarevcu čuva jednu sliku Čerkopea Barilija, portret Danice Pavlović-Barili iz 1910. godine.[14] ^ O međusobnom odnosu bračnog para Pavlović-Barili, kao i problemima koji su se javili i pre Mileninog rođenja, rečito govori jedan pasus iz Danicinih memoara, u kome se, nakon Milenine smrti, obraća Brunu: „Milena je na sigurnom kod mene... pišeš mi. ’Vidiš, ništa nije vredelo što si mi je odnela kada je još bila u tvom stomaku, kao mačke koje se ne uzdaju u svoje mužjake i odlaze da se omace negde daleko’, rekao si mi onda kada nije htela da se vrati sa mnom u Srbiju već da ostane u Rimu, kao sada.”[19] ^ Goselin se kasnije ponovo oženio i dobio ćerku koju je nazvao Mileninim imenom.

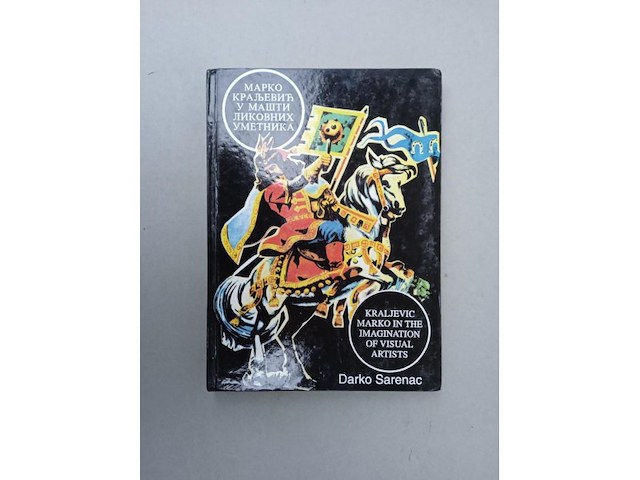

Spoljašnjost kao na fotografijama, unutrašnjost u dobrom i urednom stanju! Darko Sarenac Marko Mrnjavčević (oko 1335 — 17. maj 1395), poznatiji kao Kraljević Marko, bio je dejure srpski kralj od 1371. do 1395. godine, dok je defakto vladao samo teritorijom u zapadnoj Makedoniji. Prestoni grad u državi kralja Marka bio je Prilep. U srpskoj narodnoj epici, u kojoj mu je posvećen jedan od ciklusa pjesama, poznat je kao Kraljević Marko. Njegov otac, kralj Vukašin, bio je savladar cara Stefana Uroša V, čija je vladavina bila obilježena slabljenjem carske vlasti i osamostaljivanjem oblasnih gospodara u Srpskom carstvu, što je pospješilo njegov raspad. Vukašinovi posjedi obuhvatali su zemlje u Makedoniji, Kosovu i Metohiji. On je 1370. ili 1371. krunisao Marka za „mladog kralja“; ova titula uključivala je mogućnost da Marko nasledi Uroša na srpskom prestolu u slučaju da Uroš ne bude imao muških potomaka. Kralj srpske države U Maričkoj bici 26. septembra 1371, Turci Osmanlije porazili su i ubili Vukašina, a oko dva meseca kasnije umro je car Uroš. Marko je nakon toga zakonski postao kralj srpske države, ali srpski velikaši, koji su praktično postali nezavisni od centralne vlasti, nisu ni pomišljali da ga priznaju za svog vrhovnog gospodara. Neodređenog datuma nakon 1371. ušao je u vazalni odnos prema turskom sultanu. Do 1377. značajne dijelove teritorije koju je naslijedio od Vukašina razgrabili su gospodari okolnih oblasti. Kralj Marko je u stvarnosti postao samo jedan od oblasnih gospodara, koji je vladao relativno malim područjem u zapadnoj Makedoniji. Zadužbina mu je Manastir Svetog Dimitrija blizu Skoplja, poznat kao Markov manastir, izgrađen 1376. Poginuo je u bici na Rovinama 17. maja 1395, boreći se u Vlaškoj na strani Turaka. Iako je bio vladar relativno skromnog istorijskog značaja, Marko je tokom turske okupacije postao jedan od najpopularnijih junaka srpske narodne epike i usmene tradicije uopšte. Sličan status ima i u tradicijama drugih južnoslovenskih naroda. Bugari ga poštuju kao svog narodnog junaka pod imenom Krali Marko. Zapamćen je kao neustrašivi zaštitnik slabih i bespomoćnih, koji se borio protiv nepravde i dijelio megdane sa turskim nasilnicima. Biografija Do 1371. Marko Mrnjavčević je rođen oko 1335. godine kao najstariji sin Vukašina i njegove supruge Aljene (Alene)[1] u narodnim pesmama Jevrosime. Prema dubrovačkom istoričaru Mavru Orbinu, rodonačelnik porodice Mrnjavčević[a] bio je Mrnjava, siromašni plemić iz Zahumlja, čiji su sinovi rođeni u Livnu u zapadnoj Bosni.[3] Mrnjava se mogao tamo odseliti nakon što je Bosna anektovala Zahumlje 1326. godine.[4] Moguće je da su kasnije Mrnjavčevići, kao i drugi zahumski plemići, podržavali srpskog cara Dušana tokom njegovih priprema za pohod na Bosnu, te su se, da bi izbjegli odmazdu zbog tih aktivnosti, iselili u Srpsko carstvo pred početak sukoba.[4][5] Ove pripreme mogle su početi već dvije godine prije samog pohoda,[5] koji se dogodio 1350. Približno iz te godine potiče najraniji pisani trag o Markovom ocu Vukašinu, iz kojeg se vidi da ga je Dušan postavio za župana Prilepa.[4][6] Ovaj grad je Srbija osvojila od Vizantije 1334, skupa sa drugim dijelovima Makedonije.[7] Car Dušan je 1355. godine iznenada umro u 47. godini života.[8] Dušana je naslijedio njegov devetnaestogodišnji sin Uroš, koji je po svemu sudeći smatrao Marka Mrnjavčevića čovjekom od povjerenja. Mladi car ga je postavio na čelo svog poslanstva u Dubrovnik krajem jula 1361. godine, da bi pregovarao o miru između Carstva i Dubrovačke republike tokom sukoba koji su izbili ranije te godine.[9] Mir nije bio zaključen ovom prilikom, ali je Marko isposlovao da se puste na slobodu zarobljeni prizrenski trgovci, iako su Dubrovčani zadržali njihovu robu. Marku je takođe bilo dopušteno da podigne srebro koje je njegova porodica deponovala u tom gradu. Bilješke o ovom poslanstvu u dubrovačkim dokumentima iz te godine, sadrže prvi neosporni pisani trag o Marku Mrnjavčeviću.[10][11] U natpisu iz 1356. iznad vrata jedne crkve u Tikvešu, spominju se neki Nikola i Marko kao upravitelji u tom kraju, ali nije jasno o kojem Marku se tu radi[12] Nakon Dušanove smrti došlo je do razbuktavanja separatističkih aktivnosti u Srpskom carstvu. Jugoistočne teritorije, Epir, Tesalija i zemlje u južnoj Albaniji, ocijepile su se već do 1357.[13] Jezgro države ostalo je lojalno novom caru Urošu. Ono se sastojalo od tri glavna područja: zapadnih zemalja, uključujući Zetu, Travuniju, istočni dio Zahumlja i gornje Podrinje; središnjih srpskih zemalja; i Makedonije.[14] Ipak, velika srpska vlastela ispoljavala je sve više nezavisnosti od Uroševe vlasti čak i u tom dijelu Carstva koji je ostao srpski. Uroš je bio slab i nesposoban da u korijenu sasiječe ove separatističke težnje, postajući drugorazredan faktor u državi kojom je nominalno vladao.[15] Srpski velikaši su se i između sebe sukobljavali oko teritorija i uticaja.[16] Markov otac kralj Vukašin, freska u manastiru Psača u Severnoj Makedoniji Vukašin Mrnjavčević bio je vješt političar, i postepeno je preuzeo vodeću ulogu u Carstvu.[17] Avgusta ili septembra 1365. Uroš ga je krunisao za kralja i proglasio svojim savladarem. Do 1370. Markovo potencijalno naslijeđe je povećano, jer su se u Vukašinovom posjedu osim Prilepa našli i Prizren, Priština, Novo Brdo, Skoplje i Ohrid.[4] U povelji koju je izdao 5. aprila 1370. Vukašin je pomenuo svoju suprugu kraljicu Aljenu i sinove Marka i Andrijaša, navodeći da je Bogom postavljen za „gospodina zєmli srьbьskoi i grьkѡmь i zapadnimь stranamь“.[18] Krajem 1370. ili početkom 1371, Vukašin je krunisao Marka za „mladog kralja“.[19] Ova titula je dodjeljivana sinovima srpskih kraljeva da bi im se osigurao položaj nasljednika. Pošto Uroš nije imao djece, Marko je na ovaj način došao u poziciju da ga može naslijediti na srpskom tronu, započinjući novu—Vukašinovu—dinastiju srpskih monarha.[4] To bi predstavljalo kraj dvovjekovne vladavine Nemanjića. Većina srpskih velikaša nije bila zadovoljna ovom situacijom, što je samo ojačalo njihove težnje ka nezavisnosti od centralne vlasti.[19] Vukašin je nastojao da obezbijedi suprugu sa dobrim vezama za svog najstarijeg sina Marka. Djevojka iz dalmatinske plemićke porodice Šubić bila je poslana od strane oca Grgura na dvor njihovog rođaka bosanskog bana Tvrtka I, sa namjerom da je odgoji i dobro uda banova majka Jelena. Ona je bila ćerka Juraja II Šubića, čiji je djed po majci bio srpski kralj Dragutin Nemanjić. Pošto su Tvrtko i Jelena odobravali Vukašinovu ideju da se mlada Šubićeva uda za Marka, vjenčanje je bilo na pomolu.[20][21] Međutim, aprila 1370. rimski papa Urban V šalje pismo Tvrtku u kojem mu izričito zabranjuje da uda katoličku plemkinju za „sina njegovog veličanstva kralja Srbije, šizmatika“ (filio magnifici viri Regis Rascie scismatico).[21] Papa je o ovoj „uvredi za hrišćansku vjeru“ pisao i ugarskom kralju Lajošu I,[22] nominalno nadređenom Tvrtku, tako da od tog vjenčanja nije bilo ništa.[20] Marko se oženio Jelenom, ćerkom Radoslava Hlapena, gospodara Bera i Vodena, srpskog vladara južne Makedonije. U proljeće 1371. Marko je učestvovao u pripremama za vojni pohod protiv Nikole Altomanovića, glavnog srpskog velikaša u zapadnom dijelu Carstva. Pohod su združeno pripremali kralj Vukašin i gospodar Zete Đurađ I Balšić, koji je bio oženjen kraljevom ćerkom Oliverom. Jula te godine, Vukašin i Marko su logorovali sa svojom vojskom na Balšićevoj teritoriji kraj Skadra, spremni da naprave proboj u Altomanovićevu zemlju u pravcu Onogošta. Ovaj napad se nije dogodio, pošto su Osmanlije zaprijetile gospodaru Sera despotu Jovanu Uglješi, mlađem kraljevom bratu koji je vladao istočnom Makedonijom. Vojne snage Mrnjavčevića brzo su preusmjerene ka istoku.[24][25] Nakon bezuspješnog pokušaja da nađu saveznike, dva brata su samostalno prodrla sa svojim trupama u teritoriju pod osmanskom kontrolom. U Maričkoj bici 26. septembra 1371, Turci su potpuno uništili srpsku vojsku; čak ni tijela Vukašina i Uglješe nisu pronađena. Mjesto borbe, u blizini sela Ormenio na istoku današnje Grčke, Turci i danas nazivaju Sırp Sındığı „srpska pogibija“. Ishod ove bitke imao je ozbiljne posljedice: vrata Balkana bila su širom otvorena za dalje tursko napredovanje.[26][11] Nakon 1371. Približne granice područja kojim je vladao kralj Marko nakon 1377. godine (tamno zeleno) Poslije očeve smrti „mladi kralj“ Marko krunisan je za kralja i savladara cara Uroša. Nedugo nakon toga ugašena je dinastija Nemanjića Uroševom smrću 2. ili 4. decembra, čime je Marko formalno postao kralj srpske države. Srpski velikaši, međutim, nisu ni pomišljali da ga priznaju za svog vrhovnog gospodara, pri čemu je njihov separatizam još više porastao.[26] Pogibijom dva brata i uništenjem njihove vojske Mrnjavčevići su ostali bez stvarne moći, te su okolni oblasni gospodari prigrabili znatne dijelove teritorije koju je Marko naslijedio od svog oca. Do 1372. Đurađ I Balšić zauzeo je Prizren i Peć, a knez Lazar Hrebeljanović Prištinu. Do 1377. Vuk Branković osvojio je Skoplje, a vlastelin albanskog porijekla župan Andrija Gropa osamostalio se u Ohridu. Moguće je da je ovaj drugi ostao vazal Marku kao što je bio Vukašinu. Gropin zet bio je Markov srodnik Ostoja Rajaković od plemena Ugarčića iz Travunije. On je vjerovatno bio jedan od srpskih plemića iz Zahumlja i Travunije kojima je car Dušan dodijelio zemlje u novoosvojenim područjima Makedonije. Markove Kule, ostaci Markove tvrđave na brdu sjeverno od Prilepa Jedini značajni grad koji je Marko zadržao bio je Prilep. Tako je kralj Marko u stvarnosti postao samo jedan od oblasnih gospodara, vladar relativno male teritorije u zapadnoj Makedoniji, koja se na sjeveru prostirala do Šar-planine i Skoplja, na istoku do Vardara i Crne Reke, a na zapadu do Ohrida. Nije jasno gdje su bile južne granice ove teritorije. Marko nije sam vladao ni u ovoj oblasti, jer ju je dijelio sa mlađim bratom Andrijašem, koji je držao vlast nad jednom podoblašću u njoj. Njihova majka kraljica Aljena zamonašila se nakon Vukašinove pogibije, uzevši monaško ime Jelisaveta, ali je tokom nekoliko godina nakon 1371. bila Andrijašev savladar. Najmlađi brat Dmitar boravio je na teritoriji kojom je upravljao Andrijaš. Imali su još jednog brata koji se zvao Ivaniš, međutim o njemu je sačuvano veoma malo podataka.[30] Nejasno je kada je tačno Marko postao turski vazal, ali to se najvjerovatnije nije desilo odmah nakon Maričke bitke. Marko se jednom rastao sa svojom ženom Jelenom, te je živio sa Todorom koja je bila udata za nekog Grgura. Jelena se vratila u Ber svome ocu velmoži Radoslavu Hlapenu. Marko je kasnije tražio da se pomiri sa njom, ali da bi mu se supruga vratila, prethodno je Todoru morao da preda Hlapenu. Pošto se Markova oblast na jugu graničila sa Hlapenovom oblašću, ovo pomirenje moglo je biti motivisano činjenicom da Marku nije bio potreban neprijatelj na jugu nakon svih onih teritorijalnih gubitaka na sjeveru. Ova bračna epizoda je poznata zahvaljujući pisaru Dobri, Markovom podaniku. Dobre je prepisivao crkvenu knjigu trebnik za crkvu u selu Kaluđerec[b] i kad je završio sa poslom ostavio je zapis u knjizi koji počinje ovako: Slava sьvršitєlю bogѹ vь vѣkы, aminь, a҃mnь, a҃m. Pыsa sє siꙗ kniga ѹ Porѣči, ѹ sєlѣ zovomь Kalѹgєrєcь, vь dьnы blagovѣrnago kralꙗ Marka, ѥgda ѿdadє Ѳodoru Grьgѹrovѹ žєnѹ Hlapєnѹ, a ѹzє žєnѹ svoю prьvovѣnčanѹ Ѥlєnѹ, Hlapєnovѹ dьщєrє. Slava Savršitelju Bogu u vijeke, amin, amin, amin. Pisa se ova knjiga u Porečju, u selu zvanom Kaluđerec, u dane blagovjernog kralja Marka, kada predade Todoru Grgurovu ženu Hlapenu, a uze ženu svoju prvovjenčanu Jelenu, Hlapenovu ćerku. Freska iznad južnog ulaza u crkvu Markovog manastira. Kompozicija prikazuje kralja Marka (lijevo) i kralja Vukašina (desno) povezane polukrugom od sedam svetačkih poprsja, koji svi skupa uokviruju portret Svetog Dimitrija Markova tvrđava nalazila se na jednom brdu sjeverno od Prilepa. Njeni ostaci, djelimično dobro očuvani, poznati su pod imenom Markove Kule. Ispod tvrđave leži selo Varoš, gdje se u Srednjem vijeku prostirao grad Prilep. U selu je smješten Manastir Svetog Arhanđela Mihaila kojeg su obnovili Marko i Vukašin, čiji su portreti oslikani u manastirskoj crkvi.[23] Marko je bio ktitor Crkve Svete Nedelje u Prizrenu izgrađene 1371, nedugo pred Maričku bitku. U natpisu iznad njenih ulaznih vrata on je oslovljen titulom „mladi kralj“. Manastir Svetog Dimitrija, poznatiji kao Markov manastir, nalazi se u selu Markova Sušica u blizini Skoplja. Građen je od oko 1345. do 1376. ili 1377. Kraljevi Marko i Vukašin, njegovi ktitori, oslikani su iznad južnog ulaza u manastirsku crkvu. Marko je prikazan kao čovjek ozbiljnog lika i strogog pogleda, odjeven u purpurnu odjeću; na glavi mu je kruna ukrašena bisernim niskama. Lijevom rukom drži svitak na kojem tekst počinje riječima: „A(zь) vь H(rist)a B(og)a bla(govѣ)rьni kral(ь) Marko sьz(ь)dah(ь) i pop(i)s(a)hь (sы) božestvni hram(ь)“ (Ja, u Hrista Boga blagovjerni kralj Marko, sazidah i popisah ovaj božanstveni hram).[27] U desnoj ruci drži veliki rog koji simbolizuje rog sa uljem kojim su pomazivani starozavjetni kraljevi prilikom ustoličenja. Po jednom tumačenju, on je ovdje predstavljen kao „Božji pomazanik i izabranik u teškim prilikama Srbije posle Maričke bitke“. Marko je kovao svoj novac, kao što je činio njegov otac i drugi srpski velikaši tog doba.[34] Njegovi srebrni novčići težili su 1,11 grama, a proizvođeni su u tri osnovne vrste. Dvije na aversu imaju sljedeći tekst u pet redova: VЬHA/BABLGOV/ѢRNIKR/ALЬMA/RKO „U Hrista Boga blagovjerni kralj Marko“. Revers prikazuje Hrista—kod prve vrste na prestolu, a kod druge u mandorli. Kod treće vrste, na reversu je Hristos prikazan u mandorli, dok avers sadrži tekst u četiri reda: BLGO/VѢRNI/KRALЬ/MARKO „Blagovjerni kralj Marko“.[36] Ovu jednostavnu titulu Marko je koristio i u crkvenim natpisima. Nije u svoju titulu unosio nikakve teritorijalne odrednice, svakako jer je bio svjestan dosega svoje vlasti nakon 1371. Brat mu Andrijaš takođe je kovao svoj novac; ipak, na teritoriji kojom su braća vladala u opticaju je bilo najviše novčića kralja Vukašina i cara Uroša.[37] Procjenjuje se da se u raznim numizmatičkim zbirkama danas nalazi oko 150 komada Markovih novčića. Do 1379. gospodar Pomoravlja knez Lazar Hrebeljanović izdigao se kao prvi i najmoćniji među srpskim velikašima; potpisivao se sa titulom samodrьžcь vьsѣmь Srbьlѥmь (samodržac svih Srba). Ipak, nije bio dovoljno moćan da sve srpske zemlje ujedini pod svojom vlašću. Balšići, Mrnjavčevići, Konstantin Dragaš (Nemanjić po majci), Vuk Branković i Radoslav Hlapen, vladali su u svojim oblastima nezavisno od Kneza Lazara. Još jedan kralj pored Marka stupio je na političku scenu: Mitropolit mileševski krunisao je 1377. Tvrtka I kraljem Srba i Bosne. Ovaj rođak Nemanjića po majčinoj liniji prethodno je zauzeo jedan dio oblasti poraženog i oslijepljenog velmože Nikole Altomanovića. Dana 28. juna 1389, srpska vojska koju su predvodili knez Lazar, Vuk Branković i Tvrtkov plemić Vlatko Vuković od Zahumlja, pod vrhovnom Lazarevom komandom, sukobila se sa osmanskim trupama Sultana Murata I. Bila je to Kosovska bitka—najslavnija bitka srpske srednjovjekovne istorije. Glavnina obiju vojski bila je zbrisana; poginuli su i Lazar i Murat. Ishod bitke bio je neriješen, ali u njoj su Srbi izgubili isuviše boraca da bi mogli nastaviti sa uspješnom odbranom svojih teritorija, dok su Turci imali još mnogo trupa na istoku. Posljedično, srpske oblasti koje još nisu bile turski vazali, jedna za drugom su to postale tokom nekoliko narednih godina. Nekoliko turskih vazala na Balkanu odlučili su 1394. da raskinu svoj vazalni odnos. Marko nije bio jedan od njih, ali su njegova mlađa braća Andrijaš i Dmitar odbili da ostanu pod turskom dominacijom. U proljeće 1394. napustili su svoju zemlju i iselili se u Kraljevinu Ugarsku, stupivši u službu kralja Žigmunda. Putovali su preko Dubrovnika, gdje su se zadržali nekoliko mjeseci, dok nisu podigli dvije trećine od 96,73 kilograma srebra koje je Vukašin tamo deponovao; preostala trećina bila je namijenjena Marku. Andrijaš i Dmitar su prvi srpski plemići koji su se iselili u Ugarsku; srpske migracije prema sjeveru nastaviće se kroz čitavu osmansku okupaciju. Godine 1395. Turci su napali Vlašku da bi kaznili njenog vladara Mirču I zbog upada na njihovu teritoriju. Na turskoj strani borila su se tri vazala: kralj Marko, Konstantin Dragaš i despot Stefan Lazarević, sin i nasljednik Kneza Lazara. Bitku na Rovinama, koja se odigrala 17. maja 1395, dobili su Vlasi. Kralj Marko i Konstantin Dragaš poginuli su u njoj. Poslije njihove smrti Turci su anektovali njihove oblasti i objedinili ih u osmanski sandžak sa centrom u Ćustendilu.[43] Trideset i šest godina nakon Bitke na Rovinama Konstantin Filozof napisao je Žitije despota Stefana Lazarevića, u kojem je zabilježio predanje da je uoči bitke Marko rekao Dragašu: „Ja kažem i molim Gospoda da bude hrišćanima pomoćnik, a ja neka budem prvi među mrtvima u ovom ratu.“ Marko Kraljević i Musa Kesedžija, naslikao Vladislav Titelbah, oko 1900. Kraljević Marko je živeo u vremenima pre i malo posle bitke na Kosovu polju. Kralj Marko (vladao 1371—1395), najveća je zagonetka srpskog narodnog eposa. U Marku se sleglo vekovno istorijsko iskustvo naroda, na njega su prešle uloge i sudbine mnogih epskih junaka kako onih o kojima se pevalo pre njega tako i onih o kojima se pevalo posle njega. Iz oskudnih podataka pažnju privlače dva svedočanstva, koja nam, na gotovo neočekivan način, približavaju Marka i to više kao čoveka nego kao vladara. Prvo svedočanstvo govori o jednoj Markovoj ljubavnoj aferi. U zapisu na jednoj knjizi neki dijak Dobre bezazleno saopštava da ju je prepisao u vreme kada blagoverni kralj Marko „odade Todoru, Grgurovu ženu, Hlapenu, a uze svoju prvovenčanu ženu Jelenu, Hlapenovu kćer“ (orig. tekst ZIN, I, 1902, br. 189). Druga vest tiče se Markova učešća u bici na Rovinama, u kojoj je on, boreći se na turskoj strani, poginuo. Četrdesetak godina kasnije Konstantin Filozof (v. 1989, 90) u svom Žitiju despota Stefana piše da je Marko uoči bitke rekao Konstantinu Dejanoviću: „Ja kažem i molim Gospoda da bude hrišćanima pomoćnik, a ja neka budem prvi među mrtvima u ovom ratu.“ Prvo svedočanstvo korišćeno je u naučnoj literaturi kao objašnjenje pozadine pesme o Markovim neprilikama sa ženama. U drugom slučaju došla je do izražaja protivrečnost Markova istorijskog položaja kao ratnika koji je prinuđen da se bori na strani neprijatelja svoga naroda, protivrečnost koja čini jednu od glavnih poluga čitave markovske epike. Anegdota koju je ispričao Konstantin Filozof pokazuje da je istorijski kralj Marko bio svestan te protivrečnosti — on želi pobedu onih protiv kojih se mora boriti. Istu svest izražavaju mnoge pesme o Marku. „Portret“ Marka Kraljevića, naslikala Mina Karadžić Postoji, međutim, i jedna dublja, strukturalna podudarnost između Marka iz ovih zapisa i Marka iz epskih pesama zabeleženih nekoliko stotina godina kasnije. U oba slučaja pada u oči veliki unutrašnji raspon Markovog moralnog lika. Marko iz zapisa dijaka Dobre i Marko iz anegdote Konstantina Filozofa pojavljuju se u tako različitoj svetlosti da se za ta dva lika jedva mogu shvatiti da pripadaju istom čoveku. Prvi je ime u skandaloznoj hronici društva, a drugi tragični junak doveden u situaciju da svoju ličnu sudbinu odmerava prema kolektivnoj sudbini sveta kojem stvarno pripada, iako je prinuđen da se protiv njega bori. Razlika između ta dva lika ili između dve situacije u kojima su došle do izražaja dve dijametralno suprotne strane Markove ličnosti može se uporediti s razlikom koja postoji između Markova epskog lika iz pesama kakve su Sestra Leke kapetana, Marko Kraljević i kći kralja Arapskoga, Marko pije uz ramazan vino i slične, na jednoj, i njegovog lika iz pesama Uroš i Mrnjavčevići, Marko Kraljević ukida svadbarinu, Marko Kraljević i soko i njima bliskih, na drugoj strani. Dva navedena svedočanstva o Marku, onaj iz zapisa dijaka Dobre i onaj iz knjige Konstantina Filozofa, pokazuju da je on bio ličnost koja je još za života ušla u priču i da su se priče o njemu pamtile dugo posle njegove smrti. Konstantin Filozof na posredan način ukazuje na usmeni izvor anegdote o Markovim rečima uoči bitke na Rovinama, on tu anegdotu uvodi u tekst glagolom „kažu“, tj. priča se. Savremeni pisci ne saopštavaju ništa o tome da li se o Marku pevalo, ali iz onog što je o njemu rečeno vidi se da se o njemu pričalo, da je on bio ličnost za priču. A prirodno je da priče o ratnicima u zemlji gde postoji epska tradicija najčešće dobijaju oblik junačkih pesama. Freska svetog ratnika naoružanog šestopercom iznad glavnog ulaza u crkvu Markovog manastira Freska iznad glavnog ulaza u crkvu Markovog manastira prikazuje svetog ratnika na konju, a nastala je 1377. godine po narudžbini samog Marka Mrnjavčevića. Freska realno prikazuje vitešku opremu tog doba. Konjanik umesto mača, osnovnog oružja srednjovekovnog viteza, pomalo neočekivano u desnoj ruci nosi buzdovan šestoperac. Buzdovan je postao glavno oružje potonjeg epskog lika. Konj predstavljen na fresci je dlake koja odgovara vrsti šarac. Centralno mesto ove freske u crkvi ukazuje na to koliko je Marko Kraljević cenio viteške i vojničke osobine i da je doživljavao sebe kao viteza, a tako su ga i drugi doživljavali. Usled ovih razloga, smatra se da je ova freska poslužila narodu da stvori predstavu epskog Marka Kraljevića. Marko Kraljević iz narodnih pesama poslužio je kao inspiracija mnogim srpskim slikarima. Između ostalih, poznata su dela Paje Jovanovića, Novaka Radonića, Mine Karadžić, Vladislava Titelbaha i Petra Meseldžije. Kult Kraljevića Marka bio je razvijen i u Dalmaciji. Dva razdoblja u Markovom životu Kraljević Marko, Đura Jakšić, 1857. godine, Narodni muzej. U životu istorijskog kralja Marka jasno se izdvajaju dva perioda, do Maričke bitke i posle nje. U prvom je Markov životni put u stalnom usponu, samo što to nije bio njegov lični uspon nego uspon njegove porodice. U doba cara Uroša, Mrnjavčevići izbijaju na prvo mesto među oblasnim gospodarima: Markov otac Vukašin krunisan je za kralja i postao Urošev savladar, a stric mu Uglješa dobio je titulu despota i postao gospodar velike Serske oblasti. Sve do Maričke bitke, u kojoj su Mrnjavčevići neslavno završili, Marko se nalazio u senci svog oca. Očevom, a ne svojom zaslugom, on je dospeo na najviši položaj u državi: postao je „mladi kralj“ što je u političkom sistemu nemanjićke Srbije značilo da je određen za prestolonaslednika, a s obzirom na to da je Vukašin bio Urošev savladar i da Uroš nije imao naslednika, on je postao i prestolonaslednik carstva. Njegova vladavina, započevši „srpskom pogibijom“ na Marici, u celini je tekla u znaku tog poraza. Umesto da postane zakoniti vladar srpskog carstva, postao je kralj vazalne oblasti i podložnik turskog cara, a nije mogao da sačuva ni ono što su mu Turci ostavili. Grabljivi susedi otimali su mu deo po deo teritorija tako da je, na kraju, od prostrane države kralja Vukašina ostala mala oblast oko Prilepa. Marko je najveći gubitnik među vladarima i velikašima u tom vremenu, i inače karakterističnom po velikim nacionalnim porazima. Njegova epska sudbina korespondira i ujedno je u kontrastu prema njegovoj političkoj biografiji. On se kao junak pojavljuje u obe navedene epohe, do Maričke bitke i posle nje, i na tom globalnom planu svojom pesničkom biografijom nalazi se u saglasnosti s istorijom. Međutim, epski Marko, za razliku od istorijskog, ni u jednoj ni u drugoj eposi, ni u vremenu srpskog ni u vremenu turskog carstva, ne igra sporednu i beznačajnu ulogu. Pesma ga je izvukla iz istorijske senke i učinila glavnim junakom svog doba što je on u dubljem, pesničkom smislu zaista i bio.