Pratite promene cene putem maila

- Da bi dobijali obaveštenja o promeni cene potrebno je da kliknete Prati oglas dugme koje se nalazi na dnu svakog oglasa i unesete Vašu mail adresu.

1-7 od 7 rezultata

Broj oglasa

Prikaz

1-7 od 7

1-7 od 7 rezultata

Prikaz

Prati pretragu "radio"

Vi se opustite, Gogi će Vas obavestiti kad pronađe nove oglase za tražene ključne reči.

Gogi će vas obavestiti kada pronađe nove oglase.

Režim promene aktivan!

Upravo ste u režimu promene sačuvane pretrage za frazu .

Možete da promenite frazu ili filtere i sačuvate trenutno stanje

Aktivni filteri

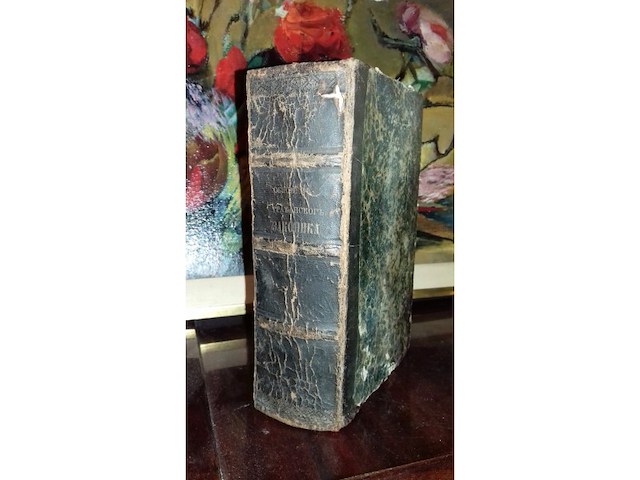

Objašnjenje građanskog zakonika za Knjažestvo Serbsko Autor: Dimitrije Matić U Beogradu, u Knjažestva Serbskog knjigopečatnici, 1850. Tvrdi povez, srpski jezik, 704 str. Knjiga se sastoji iz dva dela Za svoje godine knjiga je u veoma dobrom stanju. Kompaktna je, ne ispada ni jedna strana. Ova knjiga predstavlja objašnjenje čuvenog Građanskog zakonika Kneževine Srbije iz 1844. U to vreme srpski zakonik je, nakon francuskog, austrijskog i holandskog, bio četvrti u Evropi. Dimitrije Matić je doktorirao filozofiju u Lajpcigu. U vreme dok je pisao ovu knjigu radio je kao profesor prava na Liceju u Beogradu. Tokom života bio je i ministar prosvete kao i predsednik Skupštine.

PRVA OBJAVLJENA KNJIGA LAZE KOSTIĆA! za svoje godine knjiga je odlično očuvana korice su kao na slici, tvrd povez unutra ima pečate prethodnih vlasnika kao što se vidi na slici extra RETKO! Maksim Crnojević : tragedija u pet radnja / Napisao Laza Kostić [Novi Sad] : Izdala `Matica Srbska`, 1866 (U Novom Sadu : Episkopska štamparija) [4], 123 str. ; 23 cm Lazar „Laza“ Kostić (Kovilj, 31. januar / 12. februar 1841 — Beč, 26. novembar 1910) je bio srpski književnik, pesnik, doktor pravnih nauka advokat, poliglota, novinar, dramski pisac i estetičar. Rođen je 1841. godine u Kovilju, u Bačkoj, u vojničkoj porodici. Otac mu se zvao Petar Kostić, a majka Hristina Jovanović. Imao je i starijeg brata Andriju, ali njega i svoju majku nije upamtio jer su oni preminuli dok je Laza još bio beba. Petar Kostić, Lazin otac, preminuo je 1877. godine. Osnovnu školu je učio u mestu rođenja, gde mu je učitelj bio Gligorije Gliša Kaćanski.[1] Gimnaziju je završio u Novom Sadu, Pančevu i Budimu, a prava i doktorat prava 1866. na Peštanskom univerzitetu.[2][3][4][5] Službovanje je počeo kao gimnazijski nastavnik u Novom Sadu; zatim postaje advokat, veliki beležnik i predsednik suda. Sve je to trajalo oko osam godina, a potom se, sve do smrti, isključivo bavi književnošću, novinarstvom, politikom i javnim nacionalnim poslovima. Dvaput je dopao zatvora u Pešti: prvi put zbog lažne dostave da je učestvovao u ubistvu kneza Mihaila i drugi put zbog borbenog i antiaustrijskog govora u Beogradu na svečanosti prilikom proglašenja punoletstva kneza Milana.[6] Kad je oslobođen, u znak priznanja, bio je izabran za poslanika Ugarskog sabora, gde je, kao jedan od najboljih saradnika Svetozara Miletića, živo i smelo radio za srpsku stvar. Potom živi u Beogradu i uređuje „Srpsku nezavisnost”, ali pod pritiskom reakcionarne vlade morao je da napusti Srbiju. Na poziv kneza Nikole odlazi u Crnu Goru i tu ostaje oko pet godina, kao urednik zvaničnih crnogorskih novina i politički saradnik knežev. No i tu dođe do sukoba, pa se vrati u Bačku. U Somboru je proveo ostatak života relativno mirno. Tu je deset godina bio predsednik Srpske narodne čitaonice koja se danas po njemu naziva. U Pešti se 1892. godine susreo sa Nikolom Teslom kome je 1895. preporučio za ženidbu Lenku Dunđerski, u koju je i sam bio potajno zaljubljen. Interesantno je da je Tesla pored Lenke Dunđerski odbio i slavnu glumicu Saru Bernar.[7] Umro je 1910. god. u Beču, a sahranjen je na Velikom Pravoslavnom groblju u Somboru. Ostaće zapamćen kao jedan od najznačajnijih književnika srpskog romantizma. Izabran je za člana Srpskog učenog društva 27. februara 1883, a za redovnog člana Srpske kraljevske akademije 26. januara 1909. Književni rad Poštanska marka s likom Laze Kostića, deo serije maraka pod imenom „Velikani srpske književnosti“ koju je izdala Srbijamarka, PTT Srbija, 2010. godine Kao politički čovek i javni radnik Kostić je vršio snažan uticaj na srpsko društvo svoga vremena. On je jedan od osnivača i vođa „Ujedinjene omladine“, pokretač i urednik mnogih književnih i političkih listova, intiman saradnik Svetozara Miletića. On se u Austriji borio protiv klerikalizma i reakcije, a u Srbiji protiv birokratske stege i dinastičara. Kad je zašao u godine, napustio je svoju raniju borbenost i slobodoumlje, pa je to bio razlog što se i njegov književni rad stao potcenjivati. Kostić je svoje književno stvaranje počeo u jeku romantizma, pored Zmaja, Jakšića i drugih vrlo istaknutih pisaca. Pa ipak, za nepunih deset godina stvaranja on je stao u red najvećih pesnika i postao najpoznatiji predstavnik srpskog romantizma. Napisao je oko 150 lirskih i dvadesetak epskih pesama, balada i romansi; tri drame: Maksim Crnojević, (napisana 1863, objavljena 1866) COBISS.SR 138395143 Pera Segedinac (1882) Uskokova ljuba ili Gordana (1890); Pismo književnika Laze Kostića prijatelju Jovanu Miličiću, Sombor, 14. jula 1908. g. Pismo je muzejska građa Pozorišnog muzeja Vojvodine estetičku raspravu: Osnova lepote u svetu s osobenim obzirom na srpske narodne pesme (1880), filosofski traktat: Osnovno načelo, Kritički uvod u opštu filosofiju (1884), i veliku monografiju: O Jovanu Jovanoviću Zmaju (Zmajovi), njegovom pevanju, mišljenju i pisanju, i njegovom dobu (1902).[8] Pored većeg broja članaka polemičnog karaktera, predavanja, skica i feljtona. Od prevodilačkog rada najznačajniji su njegovi prevodi Šekspira: „Hamlet“, „Romeo i Julija“ i „Ričard III“. U prozi je napisao i nekoliko pripovedaka („Čedo vilino“, „Maharadža“, „Mučenica“). Jedna od najpoznatijih dela su mu programska pesma „Među javom i med snom“, kao i „Santa Maria della Salute“ jedna od najvrednijih lirskih pesama srpske umetničke književnosti. Preveo je udžbenik rimskog prava „Pandekta” sa nemačkog jezika 1900. godine,[9][10] u to vreme veliki deo vremena je provodio u manastiru Krušedolu.[11][12] Nasleđe Jedna novobeogradska škola od 2005. nosi ime po Lazi Kostiću. Osnovna škola u Kovilju, rodnom mestu Laze Kostića, takođe nosi njegovo ime. Od 2000. godine u Novom Sadu postoji gimnazija koja nosi ime po Lazi Kostiću i verovatno je jedina srednja škola u Srbiji koja poseduje pravu školsku pozorišnu salu sa 215 sedišta i modernom pratećom opremom za profesionalan rad [13]. Njemu u čast ustanovljene su Nagrada Laza Kostić i Nagrada Venac Laze Kostića, a u čast pesme „Santa Marija dela Salute” organizovana je u Somboru manifestacija Dan Laze Kostića, na kojoj se svakog 3. juna odabranom pesniku se dodeljuje Venac Laze Kostića. Prvi dobitnik je Pero Zubac, a 2016. godine Duško Novaković i Stojan Berber. Nagradu je 2017. godine dobio novosadski pesnik Jovan Zivlak.[14] O njemu je 1985. snimljen film Slučaj Laze Kostića. Po njemu se zove Biblioteka „Laza Kostić“ Čukarica. Rekvijem Laze Kostića Srpski novinar i publicista Ivan Kalauzović Ivanus napisao je marta 2017. godine lirsku, elegičnu pesmu „Rekvijem Laze Kostića”, zamišljenu kao nastavak poeme „Santa Maria della Salute” i omaž Lazi Kostiću. Stihove „Rekvijema...” javnost je prvi put čula u Čikagu, pre projekcije filma „Santa Maria della Salute” Zdravka Šotre u bioskopu „Century Centre”. Pred punom salom, govorila ih je novinarka nekadašnjeg Radio Sarajeva Milka Figurić.[15] Vokalno izvođenje „Rekvijema Laze Kostića” emitovano je u okviru emisije „Večeras zajedno” Prvog programa Radio Beograda aprila 2017.[16] U ulozi oratora ponovo je bila Milka Figurić, čiji se glas tada čuo na talasima Radio Beograda prvi put nakon raspada JRT sistema. dr laza kostic knjiga o zmaju srpska knjizevnost xix vek xix veka romantizam ...

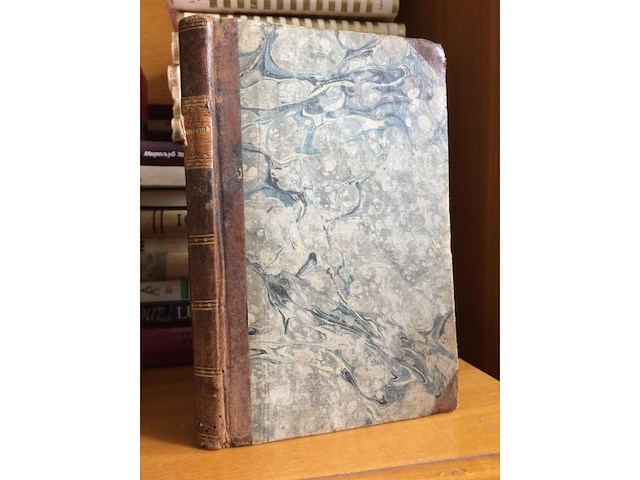

Nikolaj Šimić lepo očuvano kao na slikama izuzetno retka knjiga Іконостасъ славныхъ и храбрыхъ лицъ / Николаемъ Шимичь произведенъ Въ Будинѣ Градѣ : Писмены Кралевскаго Всеучилища Венгерскаго, 1807 138, [3] стр. ; 19 cm Садржај: Петръ Великїй ; Екатерина Вторая ; Станиславъ Аvгустъ ; Потемкинъ ; Суваровъ ; Косцїушко. Nikolaj Šimić je napisao prvu Logiku srpskog jezika. Znameniti filozofsko-prosvetiteljski pisac, direktor škola, senator i kapetan grada Sombora, Nikolaj Šimić, rođen je u Somboru 4. januara 1766. godine. U Somboru je završio osnovnu i latinsku gramatikalnu školu, gimnaziju u Segedinu, a dva tečaja filozofije (logiku i fiziku) i prava u Peštije položio i advokatski ispit. Po završetku studija otišao je u Rusiju, gde je jedno vreme bio ruski oficir kada se 1801. godine vratio iz Rusije, jedno vreme je radio kao advokat u Somboru, a posle kao senator grada Sombora i gradski kapetan. Posle penzionisanja Avrama Mrazovića 1811. godine postavljen je za direktora svih srpskih osnovnih škola u Ugarskoj. Njegova je posebna zasluga što se školska mreža proširila i na somborske salaše. Šimić je pisac mnogobrojnih knjiga, originalnih, prevedenih i prerađenih, kao što su: Logika (u dva dela), prvi sistematski priručnik logike u Srba, koji je 150 godina bio i jedina knjiga ove vrste kod nas, Ikonostas slavnih i hrabrih lic. (Biografije Petra Velikog, Katarine II, Stanislava Avgusta, Potemkina, Cyvopova i Tadeuša Košćuškog), Turčin Abdalah i Serbij Serboslava, naravoučitelenaja povest, Aristej i Acencira, egipatskaja naravoučitelnaja povijest i druge. Njegovi spisi, iako nisu originalni, izvršili su jednu određenu progresivnu kulturno-prosvetnu misiju. Znalac nekoliko jezika i široke kulture Nikolaj Šimić je jedan od najobrazovanijih i najznamenitijih Somboraca s kraja XVIII i početka XIX veka. Umro je u Somboru 1848. godine.

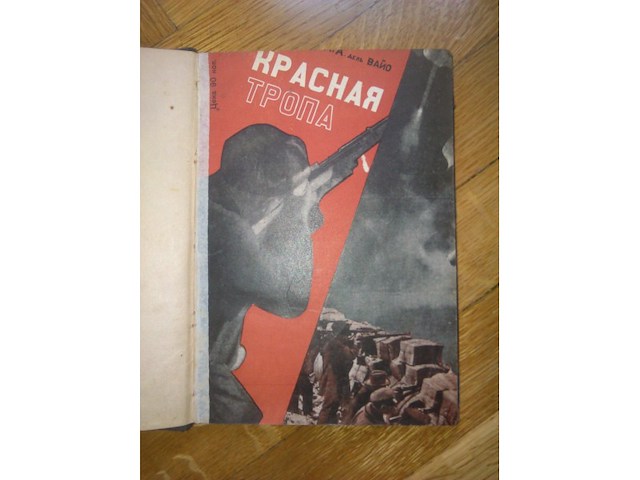

Х. А. Дель-Вайо - Красная тропа Huan Alvarez Del Vajo - Crvena staza Julio Álvarez del Vayo - Red path Moskva, 1930. Tvrd povez (naknadni), 166 strana, originalna prednja korica, na kojoj se nalazi fotomontaza jednog od najznacajnijih predstavnika sovjetske avangarde/ konstruktivizma, Gustava Klucisa. RETKO! Gustav Gustavovich Klutsis (Latvian: Gustavs Klucis, Russian: Густав Густавович Клуцис; 4 January 1895 – 26 February 1938) was a pioneering Latvian photographer and major member of the Constructivist avant-garde in the early 20th century. He is known for the Soviet revolutionary and Stalinist propaganda he produced with his wife Valentina Kulagina and for the development of photomontage techniques.[2] Born in Ķoņi parish, near Rūjiena, Klutsis began his artistic training in Riga in 1912.[3] In 1915 he was drafted into the Russian Army, serving in a Latvian riflemen detachment, then went to Moscow in 1917.[4] As a soldier of the 9th Latvian Riflemen Regiment, Klutsis served among Vladimir Lenin`s personal guard in the Smolny in 1917-1918 and was later transferred to Moscow to serve as part of the guard of the Kremlin (1919-1924).[5][6] In 1918-1921 he began art studies under Kazimir Malevich and Antoine Pevsner, joined the Communist Party, met and married longtime collaborator Valentina Kulagina, and graduated from the state-run art school VKhUTEMAS. He would continue to be associated with VKhUTEMAS as a professor of color theory from 1924 until the school closed in 1930. Klutsis taught, wrote, and produced political art for the Soviet state for the rest of his life. As the political background degraded through the 1920s and 1930s, Klutsis and Kulagina came under increasing pressure to limit their subject matter and techniques. Once joyful, revolutionary and utopian, by 1935 their art was devoted to furthering Joseph Stalin`s cult of personality. Despite his active and loyal service to the party, Klutsis was arrested in Moscow on 16 January 1938, as a part of the so-called `Latvian Operation` as he prepared to leave for the New York World`s Fair. Kulagina agonized for months, then years, over his disappearance. His sentence was passed by the NKVD Commission and the USSR Prosecutor’s Office on 11 February 1938, and he was executed on 26 February 1938, at the Butovo NKVD training ground near Moscow. He was rehabilitated on 25 August 1956 for lack of corpus delicti.[7] Work Klutsis worked in a variety of experimental media. He liked to use propaganda as a sign or revolutionary background image. His first project of note, in 1922, was a series of semi-portable multimedia agitprop kiosks to be installed on the streets of Moscow, integrating `radio-orators`, film screens, and newsprint displays, all to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Revolution. Like other Constructivists he worked in sculpture, produced exhibition installations, illustrations and ephemera. But Klutsis and Kulagina are primarily known for their photomontages. The names of some of their best posters, such as `Electrification of the whole country` (1920), `There can be no revolutionary movement without a revolutionary theory` (1927), and `Field shock workers into the fight for the socialist reconstruction` (1932), belied the fresh, powerful, and sometimes eerie images. For economy they often posed for, and inserted themselves into, these images, disguised as shock workers or peasants. Their dynamic compositions, distortions of scale and space, angled viewpoints and colliding perspectives make them perpetually modern. Klutsis is one of four artists with a claim to having invented the subgenre of political photo montage in 1918 (along with the German Dadaists Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann, and the Russian El Lissitzky).[citation needed] He worked alongside Lissitzky on the Pressa International exhibition in Cologne.[8] tags: avangarda, fotomontaza, gustav klucis, el lisicki, maljevic, suprematizam, konstruktivizam, dizajn, design, zenit, zenitizam, jo klek, nadrealizam, nadrealisti, dada, dadaizam...

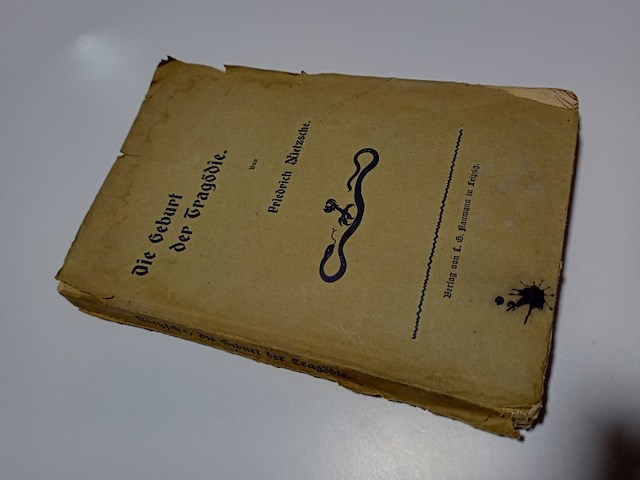

Die Geburt der Tragöödie von Friedrich Nietzsche Leipzig 1900. Rođenje tragedije Fridrih Niče Poslednje izdanje koje je izdato za života F.Niče-a, odnosno godine 1900-te, kada je on i umro. Делo, у коме је описао две супротстављене силе у грчкој драми, „Дионизијску” (културну, приказану у музици и игри) и „Аполонску” (цивилизовану, показану разумом, формалну структуру и геометрија). Fridrih Vilhelm Niče (nem. Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche; 15. oktobar 1844 — 25. avgust 1900) radikalni nemački filozof-pesnik, jedan od najvećih modernih mislilaca i jedan od najžešćih kritičara zapadne kulture i hrišćanstva. Filolog, filozof i pesnik.[1] Studirao je klasičnu filologiju i kratko vreme radio kao profesor u Bazelu, ali je morao da se povuče zbog bolesti. Na Ničea su najviše uticali Šopenhauer, kompozitor Vagner i predsokratovski filozofi, naročito Heraklit.[2] Neretko, Ničea označavaju kao jednog od začetnika egzistencijalizma, zajedno sa Serenom Kierkegarom[3] Niče je ostavio za sobom izuzetna dela sa dalekosežnim uticajem. On je jedan od glavnih utemeljivača `Lebens-philosophiae` (filozofije života), koja doživljava vaskrsenje i renesansu u `duhu našeg doba`. Detinjstvo i mladost Niče je rođen u gradu Rekenu (pored Licena), u protestantskoj porodici.[3] Njegov otac Ludvig kao i njegov deda bili su protestanski pastori. Otac mu je umro kada je imao samo 4 godine što je ostavilo dubok trag na njega. Školovao se u Pforti koja je bila izuzetno stroga škola i ostavljala učenicima jako malo slobodnog vremena. Tu je stekao i osnove poznavanja klasičnih jezika i književnosti. Bio je počeo da studira teologiju, ali se onda upisao na klasičnu filologiju.[4] Posle briljantno završenih studija, Niče je bio izvesno vreme, dok se nije razboleo, profesor u Bazelu. Doktor nauka je postao sa 24 godine bez odbrane teze zahvaljujući profesoru Ričlu koji je u njemu video veliki talenat za filologiju. Godine 1868. Niče je upoznao slavnog nemačkog kompozitora Riharda Vagnera koji je bio onoliko star koliko bi bio njegov otac da je živ.[5] Vagner i Niče su formirali odnos otac-sin i sam Niče je bio neverovatno odan Vagneru i oduševljen njime. Godine 1871.-1872. izlazi prva ničeova filozofska knjiga `Rođenje Tragedije`. Snažan uticaj Vagnerijanskih ideja koje su opet kao i Ničeove bile pod uticajem filozofije Artura Šopenhauera gotovo se može naći tokom cele knjige. Iako ima neospornu filozofsku vrednost nije pogrešno reći da je ona odbrana i veličanje Vagnerove muzike i estetike. Tokom pisanja njegove druge knjige `Nesavremena Razmatranja` (od 4 dela) Niče se filozofski osamostaljuje i raskida odnos sa Vagnerom. Godine 1889. Niče je doživeo nervni slom. Posle paralize, on je poslednjih 11 godina života proveo potpuno pomračene svesti, a o njemu su brinule majka i sestra. Inače, Ničeova najpoznatija dela su: Rođenje tragedije iz duha muzike, filozofska poema `Tako je govorio Zaratustra` (koje je prema prvobitnoj zamisli trebalo da se zove `Volja za moć, pokušaj prevrednovanja svih vrednosti`), imoralistički spis i predigra filozofije budućnosti, sa naslovom S onu stranu dobra i zla, zatim Genealogija morala, Antihrist, autobiografski esej Ecce homo i zbirka filozofskih vinjeta Volja i moć. Neosporni su Ničeovi uticaju na filozofe života, potonje mislioce egzistencije, psihoanalitičare, kao i na neke književnike, kao što su Avgust Strinberg, Džordž Bernard Šo, Andre Žid, Romen Rolan, Alber Kami, Miroslav Krleža, Martin Hajdeger i drugi. Nihilizam Nihilizam označava istorijsko kretanje Evrope kroz prethodne vekove, koje je odredio i sadašnji vek. To je vreme u kojem već dve hiljade godina preovlaadva onto-teološki horizont tumačenja sveta, hrišćanska religija i moral. [7] Niče razlikuje dve vrste nihilizma: pasivni i aktivni. Pasivni nihilizam je izraz stanja u kome postojeći vrednosti ne zadovoljavaju životne potrebe-ne znače ništa.[2] Ali on je polazište za aktivni nihilizam, za svesno odbacivanje i razaranje postojećih vrednosti, kako bi se stvorili uslovi za ponovno jedinstvo kulture i života.[2] Po sebi se razume da Niče nije izmislio nihilizam - niti je pripremio njegov dolazak, niti je prokrčio put njegovoj prevlasti u našem vremenu. NJegova je zasluga samo u tome što je prvi jasno prepoznao nihilističko lice savremenog sveta.[8] Što je prvi progovorio o rastućoj pustinji moderne bezbednosti, što je prvi glasno ustanovio da je Zapad izgubio veru u viši smisao života.[8] Niče je došao u priliku da shvati nihilizam kao prolazno, privremeno stanje. I štaviše pošlo mu je za rukom da oktrije skrivenu šansu koju nihilizam pruža današnjem čoveku.[8] Da shvati ovaj povesni događaj kao dobar znak, kao znamenje životne obnove, kao prvi nagoveštaj prelaska na nove uslove postojanja[8] Niče na jednom mestu izričito tvrdi, nihilizam je u usti mah grozničavo stanje krize s pozitivnim, a ne samo negativnim predznakom.[8] Nihilizam je zaloga buduće zrelosti života. Stoga je neopravdano svako opiranje njegovoj prevlasti, stoga je neumesna svaka borba protiv njega.[8] Natčovek Natčovek je najviši oblik volje za moć koji određuje smisao opstanka na Zemlji: Cilj nije čovečanstvo, nego više no čovek![9]. NJegov cilj je u stalnom povećanju volje za moć iz čega proizilazi da nema za cilj podređivanje natprirodnom svetu. Afirmacija sebe, a ne potčinjavanje natprirodnom, suština je Ničeove preokupacije natčovekom. U suprotnom, čovek ostaje da živi kao malograđanin u svojim životinjskim užicima kao u nadrealnom ambijentu. Natčovek je ogledalo dionizijske volje koja hoće samo sebe, odnosno večna afirmacija sveg postojećeg. Učiniti natčoveka gospodarem sveta značilo biraščovečenje postojećeg čoveka, učiniti ga ogoljenim od dosadašnjih vrednosti. Rušenjem postojećih vrednosti, što je omogućeno učenjem o večnom vraćanju istog, natčovek se otkriva kao priroda, animalnost, vladavina nesvesnog. Time Niče vrši alteraciju čoveka od tužđeg, hrišćanskog čoveka ka čoveku prirode, raščovečenom čoveku novih vrednosti. To znači da Niče suštinu čoveka određuje kao reaktivno postojanje. Na taj način čovek postojećih vrednosti mora da želi svoju propast, svoj silazak, kako bi prevazišao sebe: Mrtvi su svi bogovi, sada želimo da živi natčovek- to neka jednom u veliko podne bude naša poslednja volja![10] Čovek u dosadašnjoj istoriji nije bio sposoban da zagospodari Zemljom, jer je stalno bio usmeren protiv nje. Zbog toga čovek treba da bude nad sobom, da prevaziđe sebe. U tom pogledu natčovek ne predstavlja plod neobuzdane isprazne fantazije. Sa druge strane, prirodu natčoveka ne možemo otkriti u okviru tradicionalne-hrišćanske istorije, već je potrebno iskoračiti iz nje. Upravo ovaj iskorak može da odredi sudbinu i budućnost cele Zemlje.[7] Ničeova pisma Između Ničeove filozofije i života postoji prisna unutrašnja veza, daleko prisnija nego što je to slučaj sa ostalim filozofima.[11] Motiv usamljenosti postaje okosnica Ničeovih pisama.[11] O svojoj usamljnosti Niče je prvi put progovorio u pismima školskom drugu, prijatelju E. Rodeu, pisanim za vreme služenja vojnog roka.[11] U jednom od njih kaže da je prilično usamljen jer `u krugu svojih poznatih` nema ni prijatelja ni filologa.[12] Mladi Niče je doživeo je doživeo i shvatio usamljenost sasvim skromno i bezazleno - kao čisto spoljašnju prepreku.[11] Niče je progovorio u pismu Hajnrihu Kezelicu iz 1878[13] očigledno duboko povređen slabim prijemom na koji je naišla njegova knjiga `LJudsko, odviše ljudsko` kod njegovih prijatelja.[11] Naknadno je tačno uvideo da su unutrašnje prepreke ljudima kudikamo teži i važniji od spoljašnjih. S toga je priznao da se oseća usamljenim ne zato što je fizički udaljen od njih, već zato što je izgubio poverenje otkrivši da nema ničeg zajedničkog sa njima.[11] Jačanju i produbljivanju osećaja usamljenosti znatno je doprineo mučan rastanaka sa Lu Salome i Paulom Reeom posle kratkog ali intenzivnog druženja.[14] Poslenjih godina pred slom Niče je najzad izgubio veru u prijatelje i prijateljstvo.[11] O tome veoma upečatljivo svedoči pismo sestri u kome kaže:[11] unutra odlično očuvana listoviodlično drže korica iskrzana po obodu sve je originalno

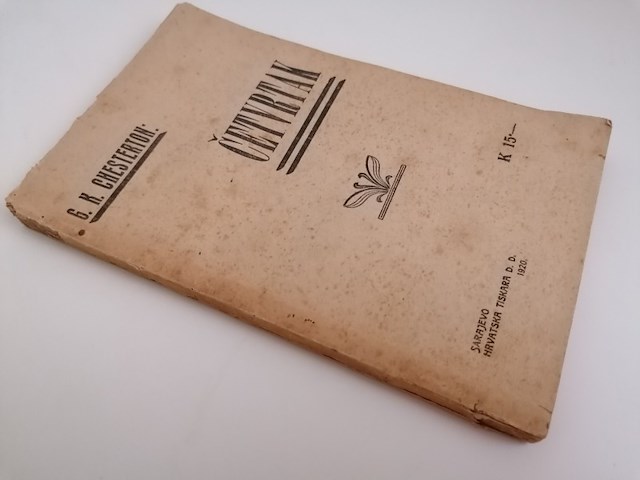

G. K. Česterton - Četvrtak 1920. - retko (Gilbert Keith Chesterton - Čovek koji je bio Četvrtak) Sarajevo, Hrvatska tiskara D.D., 1920., 177 str., mek povez, 19.5x12.5cm antikvarni kolekcionarski primerak `Čovek koji je bio četvrtak: Noćna mora` prvi put je objavljen 1908. i često nazivan `metafizičkim trilerom`. London iz viktorijanskog doba, Gabriel Syme regrutovan je u Scotland Jardu u tajni anti-anarhistički policijski korpus. Lucian Gregori, anarhistički pesnik, živi u predgrađu parka Šafran. Syme ga upoznaje na zabavi i raspravljaju o značenju poezije. Gregori tvrdi da je pobuna osnova poezije. Syme se buni, insistirajući da suština poezije nije revolucija, već zakon. Antagonira Gregorija tvrdeći da je najpoetičnije od čovekovih kreacija red vožnje za Londonsko podzemlje. Sugeriše da Gregori zapravo nije ozbiljan u vezi sa anarhizmom, što toliko iritira Gregorija da odvodi Simea na podzemno mesto anarhista, pod zakletvom da nikome ne otkriva njegovo postojanje. Centralno veće se sastoji od sedam muškaraca, od kojih svaki koristi naziv dana u nedelji kao pseudonim. ... Česterton je bio engleski književnik, a njegov bogat i raznolik stvaralački opus uključuje novinarstvo, poeziju, religiozna dela, biografiju, fantaziju i detektivsku fikciju. Bio je omiljeni Borhesov pisac, i uticao na rad Erika Artura Blera (koga znamo po imenu Džordž Orvel). ---- Gilbert Keith Chesterton (Campden Hill, 29. svibnja 1874. – London, 14. lipnja 1936.), engleski književnik, pjesnik, romanopisac, esejist, pisac kratkih priča, filozof, kolumnist, dramatičar, novinar, govornik, književni i likovni kritičar, biograf i kršćanski apologet, književnik katoličke obnove. Chestertona su nazivali `princem paradoksa` i `apostolom zdravog razuma`. Jedan je od rijetkih kršćanskih mislilaca kojemu se podjednako dive liberalni i konzervativni kršćani, a i mnogi nekršćani. Chestertonovi vlastiti teološki i politički stavovi bili su prerafinirani da bi se mogli jednostavno ocijeniti `liberalnima` ili `konzervativnima`. Za paradoks je govorio da je istina okrenuta naglavačke, da bi tako bolje privukla pozornost. Osnovano je smatrati da pripada uskome krugu najvećih književnika 20. stoljeća. 1935. je bio nominiran za Nobelovu nagradu za književnost, ali upravo te godine jedini put u povijesti dotična nije dodijeljena ta nagrada za književnost, ne računajući godine svjetskih ratova. Ne zna se sa sigurnošću razloge, ali zacijelo nije dodijeljena da je ne bi dobio veliki i djelotvorni kršćanski pisac Chesterton. Mnoge su pape cijenili Chestertona, među kojima Benedikt XVI., još dok nije bio papa, često ga je citirao, a papa Franjo još dok je bio nadbiskup Buenos Airesa, dao je Jorge Mario Bergoglio svoj blagoslov na molitvu za proglašenje Chestertona blaženim. Jedan od najvećih tomista 20. stoljeća Étienne Gilson za Chestertonovo Pravovjerje kaže da je `najbolje apologetsko djel dvadesetoga stoljeća`. Institut za vjeru i kulturu Sveučilišta Seton Hall u New Jerseyu nosi njegovo ime te izdaje znanstveni časopis The Chesterton Review. Chesterton je rođen u Campden Hillu, Kensington, London, kao sin Marie Louise (Grosjean) i Edwarda Chestertona. U dobi od jednog mjeseca bio je kršten u Crkvi Engleske. Chesterton se prema vlastitim priznanjima kao mladić zainteresirao za okultno, a sa svojim bratom Cecilom eksperimantirao je sa zvanjem duhova. Chesterton se obrazovao u Školi `St. Paul`. Pohađao je školu umjetnosti kako bi postao ilustrator, a pohađao je i satove književnosti na Londonskom sveučilišnom kolegiju, no nije završio nijedan fakultet. Chesterton se oženio za Frances Blogg 1901., i sa njom ostao do kraja svog života. Sazrijevanjem Chesterton postaje sve više ortodoksan u svojim kršćanskim uvjerenjima, kulminirajući preobraćanjem na Katoličanstvo 1922. godine. Godine 1896. počeo je raditi za londonske izdavače `Redwaya`, i `T. Fisher Unwina`, gdje je ostao sve do 1902. Tijekom ovog perioda započeo je i svoja prva honorarna djela kao novinar i književni kritičar. `Daily News` dodijelio mu je tjednu kolumnu 1902., zatim 1905. dobiva tjednu kolumnu u `The Illustrated London News`, koju će pisati narednih trideset godina. Chesterton je pokazao i veliko zanimanje i talent za umjetnost. Chesterton je obožavao debate i često se u njih upuštao sa prijateljima kao što su George Bernard Shaw, Herbert George Wells, Bertrand Russell i Clarence Darrow. Prema njegovoj autobiografiji, on i Shaw igrali su kauboje u nijemom filmu koji nikada nije izdan. Godine 1931., BBC je pozvao Chestertona na niz radijskih razgovora. Od 1932. do svoje smrti, Chesterton je isporučio više od 40 razgovora godišnje. bilo mu je dopušteno, a i bio je potican, da improvizira kod svojih obraćanja.

Dela A.N. Majkova 1884! RUS tom drugi tvrd kozni povez sjajno ocuvano posebno posle 135 godina! posveta ruski pisac skupljao prevodio i srpske epske pesme vidi slike! jako retko i vredno S. Peterburg 494 strane francuski povez Lib 20 Majkov Apolon Nikolajevič (Apollon Nikolaevič), ruski pesnik (Moskva, 4. VI. 1821 – Sankt Peterburg, 20. III. 1897). Studirao pravo; radio kao knjižar, od 1852. cenzor. Pristalica »naturalne škole« (poema Mašenka, 1846), poslije historicist (Kraj groba Groznoga – U groba Groznogo, 1887) i religijsko-filozofski lirik (mistifikacija Iz Apollodora Gnostika, 1877–93). U pjesništvu prevladavaju antički i talijanski motivi, krajolici. Objavio ciklus Iz slavenskog svijeta (Iz slavjanskogo mira, 1870–80). Apollon Nikolayevich Maykov (Russian: Аполло́н Никола́евич Ма́йков, June 4 [O.S. May 23] 1821, Moscow – March 20 [O.S. March 8] 1897, Saint Petersburg) was a Russian poet, best known for his lyric verse showcasing images of Russian villages, nature, and history. His love for ancient Greece and Rome, which he studied for much of his life, is also reflected in his works. Maykov spent four years translating the epic The Tale of Igor`s Campaign (1870) into modern Russian. He translated the folklore of Belarus, Greece, Serbia and Spain, as well as works by Heine, Adam Mickiewicz and Goethe, among others. Several of Maykov`s poems were set to music by Russian composers, among them Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky. Maykov was born into an artistic family and educated at home, by the writer Ivan Goncharov, among others. At the age of 15, he began writing his first poetry. After finishing his gymnasium course in just three years, he enrolled in Saint Petersburg University in 1837. He began publishing his poems in 1840, and came out with his first collection in 1842. The collection was reviewed favorably by the influential critic Vissarion Belinsky. After this, he traveled throughout Europe, returning to Saint Petersburg in 1844, where he continued to publish poetry and branched out into literary criticism and essay writing. He continued writing throughout his life, wavering several times between the conservative and liberal camps, but maintaining a steady output of quality poetical works. In his liberal days he was close to Belinsky, Nikolay Nekrasov, and Ivan Turgenev, while in his conservative periods he was close to Fyodor Dostoyevsky. He ended his life as a conservative. Maykov died in Saint Petersburg On March 8, 1897. Contents 1 Biography 1.1 Literary career 1.1.1 Maykov and revolutionary democrats 1.1.2 The Tale of Igor`s Campaign 1.1.3 Christianity and paganism 1.1.4 Last years 2 Legacy 3 Selected bibliography 3.1 Poetry collections 3.2 Dramas 3.3 Major poems 4 Notes 5 References 6 External links Biography Apollon Maykov was born into an artistic family. His father, Nikolay Maykov, was a painter, and in his later years an academic of the Imperial Academy of Arts. His mother, Yevgeniya Petrovna Maykova (née Gusyatnikova, 1803–1880), loved literature and later in life had some of her own poetry published.[1] The boy`s childhood was spent at the family estate just outside Moscow, in a house often visited by writers and artists.[2] Maykov`s early memories and impressions formed the foundation for his much lauded landscape lyricism, marked by what biographer Igor Yampolsky calls `a touchingly naive love for the old patriarchal ways.`[3] In 1834 the family moved to Saint Petersburg. Apollon and his brother Valerian were educated at home, under the guidance of their father`s friend Vladimir Solonitsyn, a writer, philologist and translator, known also for Nikolay Maykov`s 1839 portrait of him. Ivan Goncharov, then an unknown young author, taught Russian literature to the Maykov brothers. As he later remembered, the house `was full of life, and had many visitors, providing a never ceasing flow of information from all kinds of intellectual spheres, including science and the arts.`[4] At the age of 15 Apollon started to write poetry.[5] With a group of friends (Vladimir Benediktov, Ivan Goncharov and Pavel Svinyin among others) the Maykov brothers edited two hand-written magazines, Podsnezhnik (Snow-drop) and Moonlit Nights, where Apollon`s early poetry appeared for the first time.[1] Maykov finished his whole gymnasium course in just three years,[3] and in 1837 enrolled in Saint Petersburg University`s law faculty. As a student he learned Latin which enabled him to read Ancient Roman authors in the original texts. He later learned Ancient Greek, but until then had to content himself with French translations of the Greek classics. It was at the university that Maykov developed his passionate love of Ancient Greece and Rome.[3] Literary career Apollon Maykov`s first poems (signed `M.`) were published in 1840 by the Odessa Almanac and in 1841 by Biblioteka Dlya Chteniya and Otechestvennye Zapiski. He also studied painting, but soon chose to devote himself entirely to poetry. Instrumental in this decision was Pyotr Pletnyov, a University professor who, acting as a mentor for the young man, showed the first poems of his protégé to such literary giants as Vasily Zhukovsky and Nikolai Gogol. Maykov never became a painter, but the lessons he received greatly influenced his artistic worldview and writing style.[1] In 1842 his first collection Poems by A.N. Maykov was published, to much acclaim. `For me it sounds like Delvig`s ideas expressed by Pushkin,` Pletnyov wrote.[6] Vissarion Belinsky responded with a comprehensive essay,[7] praising the book`s first section called `Poems Written for an Anthology`, a cycle of verses stylized after both ancient Greek epigrams and the traditional elegy. He was flattered by the famous critic`s close attention.[note 1] Maykov paid heed to his advice and years later, working on the re-issues, edited much of the text in direct accordance with Belinsky`s views.[8] After graduating from the university, Maykov joined the Russian Ministry of Finance as a clerk. Having received a stipend for his first book from Tsar Nicholas I, he used the money to travel abroad, visiting Italy (where he spent most of his time writing poetry and painting), France, Saxony, and Austria. In Paris Apollon and Valerian attended lectures on literature and fine arts at the Sorbonne and the College de France.[5] On his way back Maykov visited Dresden and Prague where he met Vaclav Hanka and Pavel Jozef Safarik, the two leaders of the national revival movement.[3] The direct outcome of this voyage for Apollon Maykov was a University dissertation on the history of law in Eastern Europe.[5] Maykov circa 1850 In 1844 Maykov returned to Saint Petersburg to join the Rumyantsev Museum library as an assistant. He became actively involved with the literary life of the Russian capital, contributing to Otechestvennye Zapiski, Finsky Vestnik and Sovremennik. He also debuted as a critic and published several essays on literature and fine art, reviewing works by artists like Ivan Aivazovsky, Fyodor Tolstoy and Pavel Fedotov.[1] In 1846 the Petersburg Anthology published his poem `Mashenka`, which saw Maykov discarding elegy and leaning towards a more down-to-Earth style of writing. Again Belinsky was impressed, hailing the arrival of `a new talent, quite capable of presenting real life in its true light.`[9] The critic also liked Two Fates (Saint Petersburg, 1845). A `natural school` piece, touched by Mikhail Lermontov`s influence, it featured `a Pechorin-type character, an intelligent, thinking nobleman retrogressing into a low-brow philistine,` according to Alexander Hertzen`s review.[10] In the late 1840s Maykov was also writing prose, in a Gogol-influenced style known as the `physiological sketch`. Among the short stories he published at the time were `Uncle`s Will` (1847) and `The Old Woman – Fragments from the Notes of a Virtuous Man` (1848).[1] In the late 1840s Maykov entered Belinsky`s circle and became friends with Nikolai Nekrasov and Ivan Turgenev. Along with his brother Valerian he started to attend Mikhail Petrashevsky`s `Secret Fridays`, establishing contacts with Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Aleksey Pleshcheyev. Later, having been interrogated about his involvement, Maykov avoided arrest (he did not have a significant role in the group`s activities), but for several years was kept under secret police surveillance.[1] In the years to come Maykov, who never believed in the ideas of socialism, often expressed embarrassment over his involvement in the Petrashevsky affair. In an 1854 letter to M. A. Yazykov he confessed: `At the time I had very vague political ideas and was foolish enough to join a group where all the government`s actions were criticized and condemned as wrong a priory, many of [its members] applauding every mistake, according to the logic of `the worse they rule, the quicker they`ll fall`.[11] In the 1850s Maykov, now a Slavophile, began to champion `firm` monarchy and strong Orthodox values.[2] Writing to Aleksandr Nikitenko he argued: `Only a form of political system which had been proven by the test of history could be called viable`.[12] In 1852 Maykov moved into the office of the Russian Committee of Foreign censorship, where he continued working for the rest of his life, becoming its chairman in 1882.[1] In 1847 Maykov`s second collection of poems, Sketches of Rome, the artistic outcome of his earlier European trip, was published. Informed with Belinsky`s criticism, some poems were built on the juxtaposition of the majestic ruins and lush landscapes of `classic` Rome with the everyday squalor of contemporary Italy. This homage to the `natural school` movement, though, did not make Maykov`s style less flamboyant; on the contrary, it was in Sketches of Rome that he started to make full use of exotic epithets and colorful imagery.[1] In 1848–1852 Maykov wrote little, but became active during the Crimean War. First came the poem `Claremont Cathedral` (1853), an ode to Russia`s historical feat of preventing the Mongol hordes from devastating European civilization.[note 2] This was followed by the compilation Poems, 1854. Some of the poems, like those about the siege of Sevastopol (`To General-Lieutenant Khrulyov`) were welcomed by the literary left (notably Nekrasov and Chernyshevsky). Others (`In Memory of Derzhavin` and `A Message to the Camp`) were seen as glorifying the monarchy and were deemed `reactionary`.[13] The last 1854 poem, `The Harlequin`, was a caricature on a revolutionary keen to bring chaos and undermine centuries-old moral principles.[13] Now a `patriarchal monarchist`, Maykov started to praise the Nikolai I regime. Another poem, `The Carriage`, where Maykov openly supported the Tsar, was not included in 1854, but circulated in its hand-written version and did his reputation a lot of harm. Enemies either ridiculed the poet or accused him of political opportunism and base flattery. Some of his friends were positively horrified. In his epigrams, poet Nikolay Shcherbina labeled Maykov `chameleon` and `servile slave`.[1] While social democrats (who dominated the Russian literary scene of the time) saw political and social reforms as necessary for Russia, Maykov called for the strengthening of state power.[13] After Russia`s defeat in the war the tone of Maykov`s poetry changed. Poems like `The war is over. Vile peace is signed...`, `Whirlwind` (both 1856), `He and Her` (1867) criticized corrupt high society and weak, inadequate officials who were indifferent to the woes of the country and its people.[13] Now openly critical of Nikolai I, Maykov admitted to having been wrong when professing a belief in the monarch.[14] Maykov in the 1850s In 1858 Maykov took part in the expedition to Greece on board the corvette Bayan. Prior to that he read numerous books about the country and learned the modern Greek language. Two books came out as a result of this trip: The Naples Album (which included `Tarantella`, one of his best known poems) and Songs of Modern Greece. The former, focusing on contemporary Italian life, was coldly received by Russian critics who found it too eclectic. In retrospect it is regarded as a curious experiment in breaking genre barriers, with images and conversations from foreign life used to express things which in Russia could not be commented on publicly at the time.[13] In the latter, the author`s sympathy for the Greek liberation movement is evident.[3] The early 1860s saw Maykov`s popularity on the rise: he often performed in public and had his works published by the leading Russian magazines.[15] In the mid-1860s he once again drifted towards the conservative camp, and stayed there for the rest of his life. He condemned young radicals, and expressed solidarity with Mikhail Katkov`s nationalistic remarks regarding the Polish Uprising and Russian national policy in general. In poems like `Fields` (which employed Gogol`s metaphor of Russia as a troika, but also expressed horror at emerging capitalism),[13] `Niva` and `The Sketch` he praised the 1861 reforms, provoking sharp criticism from Saltykov-Schedrin[16] and Nikolay Dobrolyubov.[2] Adopting the Pochvennichestvo doctrine, Maykov became close to Apollon Grigoriev, Nikolai Strakhov, and Fyodor Dostoyevsky; his friendship with the latter proved to be a particularly firm and lasting one.[1] In the 1860s and 1870s Maykov contributed mainly to Russky Vestnik.[3] One of the leading proponents of Russian Panslavism, he saw his country as fulfilling its mission in uniting Slavs, but first and foremost freeing the peoples of the Balkans from Turkish occupation. `Once you`ve seen Russia in this [Panslavic] perspective, you start to understand its true nature and feel ready to devote yourself to this life-affirming cause,` wrote Maykov in a letter to Dostoyevsky.[17] The mission of art, according to the poet, was to develop the national self-consciousness and revive the `historical memory` of Russians. The Slavic historic and moral basis on which it stood became the major theme of Maykov`s poetry cycles `Of the Slavic World`, `At Home`, and `Callings of History`. Well aware of the darker side of Russia`s historic legacy, he still thought it necessary to highlight its `shining moments` (`It`s dear to me, before the icon...`, 1868). Maykov was not a religious person himself but attributed great importance to the religious fervor of the common people, seeing it as the basis for `moral wholesomeness` (`The spring, like an artist`, 1859; `Ignored by all...`, 1872). His religious poems of the late 1880s (`Let go, let go...`, `The sunset’s quiet shine...`, `Eternal night is near...`) differed radically from his earlier odes to paganism. In them Maykov professed a belief in spiritual humility and expressed the conviction that this particular feature of the Russian national character would be its saving grace.[13] Maykov and revolutionary democrats Unlike his artistic ally Afanasy Fet, Maykov always felt the need for maintaining `spiritual bonds` with common people and, according to biographer Yampolsky, followed `the folk tradition set by Pushkin, Lermontov, Krylov and Koltsov`.[3] Yet he was skeptical of the doctrine of narodnost as formulated by Dobrolyubov and Chernyshevsky, who saw active promotion of the democratic movement as the mission of Russian literature. In 1853, horrified by Nekrasov`s poem `The Muse`, Maykov wrote `An Epistle to Nekrasov`, in which he urged the latter to `dilute his malice in nature`s harmony.` Yet he never severed ties with his opponent and often gave him credit. `There is only one poetic soul here, and that is Nekrasov,` Maykov wrote in an October 1854 letter to Ivan Nikitin.[18] According to Yampolsky, Nekrasov`s poem `Grandfather` (1870, telling the story of a nobleman supporting the revolutionary cause) might have been an indirect answer to Maykov`s poem `Grandmother` (1861) which praised the high moral standards of the nobility and condemned the generation of nihilists. Maykov`s poem Princess (1876) had its heroine Zhenya, a girl from an aristocratic family, join a gang of conspirators and lose all notions of normality, religious, social or moral. However, unlike Vsevolod Krestovsky or Viktor Klyushnikov, Maykov treated his `nihilist` characters rather like victims of the post-Crimean war social depression rather than villains in their own right.[3] The Tale of Igor`s Campaign Seeking inspiration and moral virtue in Russian folklore, which he called `the treasury of the Russian soul`, Maykov tried to revive the archaic Russian language tradition.[19] In his later years he made numerous freestyle translations and stylized renditions of Belarussian and Serbian folk songs. He developed a strong interest in non-Slavic folklore too, exemplified by the epic poems Baldur (1870) and Bringilda (1888) based on the Scandinavian epos.[3] In the late 1860s Maykov became intrigued by The Tale of Igor`s Campaign, which his son was studying in gymnasium at the time. Baffled by the vagueness and occasional incongruity of all the available translations, he shared his doubts with professor Izmail Sreznevsky, who replied: `It is for you to sort these things out.` Maykov later described the four years of work on the new translation that followed as his `second university`.[3] His major objective was to come up with undeniable proof of the authenticity of the old text, something that many authors, Ivan Goncharov among them, expressed doubts about. Ignoring Dostoyevsky`s advice to use rhymes so as to make the text sound more modern, Maykov provided the first ever scientifically substantiated translation of the document, supplied with comprehensive commentaries. First published in the January 1870 issue of Zarya magazine, it is still regarded as one of the finest achievements of his career.[13] For Maykov, who took his historical poems and plays seriously, authenticity was the main objective. In his Old Believers drama The Wanderer (1867), he used the hand-written literature of raskolniks and, `having discovered those poetic gems, tried to re-mold them into... modern poetic forms,` as he explained in the preface.[20][13] In his historical works Maykov often had contemporary Russian issues in mind. `While writing of ancient history I was looking for parallels to the things that I had to live through. Our times provide so many examples of the rise and fall of the human spirit that an attentive eye looking for analogies can spot a lot,` he wrote.[21] Christianity and paganism Maykov in his later years Maykov`s first foray into the history of early Christianity, `Olynthus and Esther` (1841) was criticized by Belinsky. He returned to this theme ten years later in the lyrical drama Three Deaths (1857), was dissatisfied with the result, and went on to produce part two, `The Death of Lucius` (1863). Three Deaths became the starting point of his next big poem, Two Worlds, written in 1872, then re-worked and finished in 1881. Following Belinsky`s early advice, Maykov abandoned Lucius, a weak Epicurean, and made the new hero Decius, a patrician who, while hating Nero, still hopes for the state to rise up from its ashes.[13] Like Sketches of Rome decades earlier, Two Worlds was a eulogy to Rome`s eternal glory, its hero fighting Christianity, driven by the belief that Rome is another Heaven, `its dome embracing Earth.`[5] While in his earlier years Maykov was greatly intrigued by antiquity, later in life he became more interested in Christianity and its dramatic stand against oppressors. While some contemporaries praised Maykov for his objectivity and scholarly attitude, the Orthodox Christian critics considered him to be `too much of a heathen` who failed to show Christianity in its true historical perspective.[22] Later literary historians viewed Maykov`s historical dramas favourably, crediting the author for neutrality and insight. Maykov`s antiquity `lives and breathes, it is anything but dull,` wrote critic F. Zelinsky in 1908.[23] For the Two Worlds Maykov received The Russian Academy of Sciences` Pushkin Prize in 1882.[1] Last years In 1858 Grigory Kushelev-Bezborodko published the first Maykov anthology Poems by Ap. Maykov. In 1879 it was expanded and re-issued by Vladimir Meshchersky. The Complete Maykov came out in 1884 (its second edition following in 1893).[5] In the 1880s Maykov`s poetry was dominated by religious and nationalistic themes and ideas. According to I. Yampolsky, only a few of his later poems (`Emshan`, `The Spring`, 1881) had `indisputable artistic quality`.[3] In his later years the poet wrote almost nothing new, engaging mostly in editing his earlier work and preparing them for compilations and anthologies. `Maykov lived the quiet, radiant life of an artist, evidently not belonging to our times... his path was smooth and full of light. No strife, no passions, no persecution,` wrote Dmitry Merezhkovsky in 1908.[24] Although this generalization was far from the truth, according to biographer F. Priyma, it certainly expressed the general public`s perception of him.[13] Apollon Maykov died in Saint Petersburg On March 8, 1897. `His legacy will always sound as the mighty, harmonious and very complicated final chord to the Pushkin period of Russian poetry,` wrote Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov in the Ministry of Education`s obituary.[25] Legacy Maykov`s initial rise to fame, according to the Soviet scholar Fyodor Pryima, had a lot to do with Pushkin and Lermontov`s untimely deaths, and the feeling of desolation shared by many Russian intellectuals of the time.[13] Vissarion Belinsky, who discovered this new talent, believed it was up to Maykov to fill this vacuum. `The emergence of this new talent is especially important in our times, when in the devastated Church of Art... we see but grimacing jesters entertaining dumb obscurants, egotistic mediocrities, merchants and speculators,` Belinsky wrote, reviewing Maykov`s debut collection.[26] The sleeve of Poems by Apollon Maykov in 2 volumes, 1858. Hailing the emergence of a new powerful talent, Belinsky unreservedly supported the young author`s `anthological` stylizations based upon the poetry of Ancient Greece, praising `the plasticity and gracefulness of the imagery,` the virtuosity in the art of the decorative, the `poetic, lively language` but also the simplicity and lack of pretentiousness.[27] `Even in Pushkin`s legacy this poem would have rated among his best anthological pieces,` Belinsky wrote about the poem called `The Dream`.[28] Still, he advised the author to leave the `anthological` realm behind as soon as possible[29] and expressed dissatisfaction with poems on Russia`s recent history. While admitting `Who`s He` (a piece on Peter the Great, which some years later found its way into textbooks) was `not bad`, Belinsky lambasted `Two Coffins`, a hymn to Russia`s victories over Karl XII and Napoleon. Maykov`s debut collection made him one of the leading Russian poets. In the 1840s `his lexical and rhythmic patterns became more diverse but the style remained the same, still relying upon the basics of classical elegy,` according to the biographer Mayorova, who noted a strange dichotomy between the flamboyant wording and static imagery, and pointed to the `insurmountable distance between the poet and the world he pictured.`[1] After Belinsky`s death, Maykov started to waver between the two camps of the Westernizers and the Slavophiles, and the critics, accordingly, started to treat his work on the basis of their own political views in relation to the poet`s changing ideological stance. Maykov`s 1840s` `natural school`- influenced poems were praised (and published)[30] by Nikolay Nekrasov. His later works, expressing conservative, monarchist and anti-`nihilist` views, were supported by Dostoyevsky, who on more than one occasion pronounced Maykov Russia`s major poet.[13][31] In his 1895 article for the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, the philosopher and critic Vladimir Solovyov argued that Maykov`s dominant characteristics were `a serene, contemplating tone, elaborate patterns, a distinct and individual style (in form, although not in colors) with a relatively lackluster lyric side, the latter suffering obviously from too much attention to details, often at the expense of the original inspiration.` Maykov`s best works were, the critic opined, `powerful and expressive, even if not exceptionally sonorous.`[5] Speaking of Maykov`s subject matter, Solovyov was almost dismissive: Two major themes form the foundation of Maykov`s poetry, the Ancient Greek aesthetic and historical myths of the Byzantine-Russian politics; bonded only by the poet`s unreserved love for both, never merge... The concept of Byzantium, as the second Rome, though, has not crystallized as clear and distinct in the poet`s mind as that of the original Roman Empire. He loves Byzantine/Russia in its historical reality, refusing to admit its faults and contradictions, tending to glorify even such monsters as Ivan the Terrible, whose `greatness`, he believes, will be `recognised` in due time. [...] There was also a kind of background theme in his earlier work, the pastoral pictures of beautiful Russian nature, which the poet had all the better reason to enjoy for being a devout fisherman.[5] Autograph by Apollon Maikov of his poem `Pustinnik` (Hermit) The modernist critic Yuly Aykhenvald, analyzing the cliché formula that bonded `Maykov, Polonsky and Fet` into a solid group of similar-minded authors, alleged that Maykov `to a lesser extent than the other two freed himself from the habit of copying classics` and `in his earlier works was unoriginal, producing verse that shone with reflected light.` Not even his passionate love for classics could help the author submerge `wholly into the pagan element,` the critic opined.[32] He was a scholar of antiquity and his gift, self-admittedly `has been strengthened by being tempered in the fire of science.` As a purveyor of classicism, his very soul was not deep or naive enough to fully let this spirit in or embrace the antique idea of intellectual freedom. Poems, inhabited by naiads, nymphs, muses and dryads, are very pretty, and you can`t help being enchanted by these ancient fables. But he gives you no chance to forget for a moment that – what for his ancient heroes was life itself, for him is only a myth, a `clever lie` he could never believe himself.[32] All Maykov`s strong points, according to the critic, relate to the fact that he learned painting, and, in a way, extended the art into his poetry. Aykhenvald gives him unreserved credit for the `plasticity of language, the unequalled turn at working on a phrase as if it was a tangible material.` Occasionally `his lines are so interweaved, the verse looks like a poetic calligraphy; a scripturam continuam... Rarely passionate and showing only distant echoes of original inspiration, Maykov`s verse strikes you with divine shapeliness... Maykov`s best poems resemble statues, driven to perfection with great precision and so flawless as to make a reader feel slightly guilty for their own imperfection, making them inadequate to even behold what`s infinitely finer than themselves,` the critic argued.[32] Another Silver Age critic who noticed how painting and fishing might have influenced Maykov`s poetry was Innokenty Annensky. In his 1898 essay on Maykov he wrote: `A poet usually chooses their own, particular method of communicating with nature, and often it is sports. Poets of the future might be cyclists or aeronauts. Byron was a swimmer, Goethe a skater, Lermontov a horse rider, and many other of our poets (Turgenev, both Tolstoys, Nekrasov, Fet, Yazykov) were hunters. Maykov was a passionate fisherman and this occupation was in perfect harmony with his contemplative nature, with his love for a fair sunny day which has such a vivid expression in his poetry.`[33] Putting Maykov into the `masters of meditation` category alongside Ivan Krylov and Ivan Goncharov, Annensky continued: `He was one of those rare harmonic characters for whom seeking beauty and working upon its embodiments was something natural and easy, nature itself filling their souls with its beauty. Such people, rational and contemplative, have no need for stimulus, praise, strife, even fresh impressions... their artistic imagery growing as if from soil. Such contemplative poets produce ideas that are clear-cut and `coined`, their images are sculpture-like,` the critic argued.[33] Annensky praised Maykov`s gift for creating unusual combinations of colors, which was `totally absent in Pushkin`s verse, to some extent known to Lermontov, `a poet of mountains and clouds` ...and best represented by the French poets Baudelaire and Verlaine.` `What strikes one is Maykov`s poetry`s extraordinary vigor, the freshness and firmness of the author`s talent: Olympians and the heroes of Antiquity whom he befriended during his childhood years… must have shared with him their eternal youth,` Annensky wrote.[33] Maykov in 1868 D. S. Mirsky called Maykov `the most representative poet of the age,` but added: `Maykov was mildly `poetical` and mildly realistic; mildly tendentious, and never emotional. Images are always the principal thing in his poems. Some of them (always subject to the restriction that he had no style and no diction) are happy discoveries, like the short and very well known poems on spring and rain. But his more realistic poems are spoiled by sentimentality, and his more `poetic` poems hopelessly inadequate — their beauty is mere mid-Victorian tinsel. Few of his more ambitious attempts are successful.`[34] By the mid-1850s Maykov had acquired the reputation of a typical proponent of the `pure poetry` doctrine, although his position was special. Yet, according to Pryima, `Maykov was devoid of snobbishness and never saw himself occupying some loftier position even when mentioning `crowds`. His need in communicating with people is always obvious (`Summer Rain`, `Haymaking`, `Nights of Mowing`, The Naples Album). It`s just that he failed to realize his potential as a `people`s poet` to the full.` `Maykov couldn`t be seen as equal to giants like Pushkin, Lermontov, Koltsov, or Nekrasov,` but still `occupies a highly important place in the history of Russian poetry` which he greatly enriched, the critic insisted.[13] In the years of Maykov`s debut, according to Pryima, `Russian poetry was still in its infancy... so even as an enlightener, Maykov with his encyclopedic knowledge of history and the way of approaching every new theme as a field for scientific research played an unparalleled role in the Russian literature of the time.` `His spectacular forays into the `anthological` genre, as well as his translations of classics formed a kind of `antique Gulf Stream` which warmed up the whole of Russian literature, speeding its development,` another researcher, F. F. Zelinsky, agreed.[13] Maykov`s best poems (`To a Young Lady`, `Haymaking`, `Fishing`, `The Wanderer`), as well his as translations of the Slavic and Western poets and his poetic rendition of Slovo o Polku Igoreve, belong to the Russian poetry classics, according to Pryima.[13] Selected bibliography Poetry collections Poems by A.N.Maykov (1842) Sketches of Rome (Otcherki Rima, 1847) 1854. Poems (Stikhotvoreniya, 1854) The Naples Album (Neapolsky albom, 1858) Songs of Modern Greece (Pesni novoy Gretsii, 1860) Dramas Three Deaths (Tri smerti, 1857) Two Worlds (Dva mira, 1882) Major poems Two Fates (Dve sudby, 1845) Mashenka (1946) Dreams (Sny, 1858) The Wanderer (Strannik, 1867) Princess*** (Knyazhna, 1878) Bringilda (1888)