Pratite promene cene putem maila

- Da bi dobijali obaveštenja o promeni cene potrebno je da kliknete Prati oglas dugme koje se nalazi na dnu svakog oglasa i unesete Vašu mail adresu.

126-127 od 127 rezultata

Prati pretragu "radio"

Vi se opustite, Gogi će Vas obavestiti kad pronađe nove oglase za tražene ključne reči.

Gogi će vas obavestiti kada pronađe nove oglase.

Režim promene aktivan!

Upravo ste u režimu promene sačuvane pretrage za frazu .

Možete da promenite frazu ili filtere i sačuvate trenutno stanje

Aktivni filteri

-

Tag

Političke nauke

Majkl Ferbenks, Stejs Lindzej - Oranje mora (podsticanje skrivenih izvora rasta u zemljama u razvoju) Stubovi kulture, 2003. Ivan Radosavljević(prevod) Naslov originala: Plowing the Sea / Michael Fairbanks & Stace Lindsay Potpis prethodnog vlasnika na predlistu, inače odlično očuvana. Pred nama je delo koje predstavlja pravi i izuzetno koristan vodič za zemlje u razvoju. Sačinjeno je iz niza priča i iskustava koje su autori imali u svojoj praksi, kao i da je namenjeno kako običnom, tako i čitaocu sa najvišim poznavanjem ekonomskih nauka. Kako orati more? `Srbija, nažalost, ima ogroman kapacitet da bude u krizi, a da se ne promeni. Ima strahovit potencijal da oseća bol, a da se ne menja. To je neverovatno` Razgovor vodio Miša Brkić Kako orati more? KULTURA, MEDIJI I NAPREDAK: Majkl Ferbanks Šta bi moglo biti zajedničko u preusmeravanju namenske proizvodnje u Kaliforniji, petrohemijske i kožarske industrije u Kolumbiji, agro i tekstilne industrije u Peruu, turizma u Irskoj, telekomunikacija u Egiptu, bankarstva i finansija u Nigeriji, restrukturiranju vojne industrije i stvaranju okruženja malih preduzeća u Rusiji, drvne industrije u Boliviji i podizanju konkurentnosti proizvođača i prerađivača voća u Srbiji? `Mirođija` u svim spomenutim poslovama bio je Majkl Ferbanks, jedan od šefova kompanije Monitor, predsednik Upravnog odbora konsultantske grupe OTF (On the Frontier) i već više od decenije savetnik vlada i privatnih kompanija širom sveta za primenu teorije konkurentnosti. Među njegove klijente spadaju premijeri, ministri i izvršni direktori najvećih svetskih firmi, savetovao je najviše službenike u Svetskoj banci ali i u razvojnim bankama u Africi i Južnoj Americi. Na poziv Nacionalnog saveta za konkurentnost boravio je u Beogradu, gde je predstavio srpsko izdanje svoje knjige Oranje mora (Plowing the Sea) u kojoj objašnjava izvore stalnog prosperiteta država u modernoj globalnoj ekonomiji. `Globalizacija nemilosrdno kažnjava osrednjost, prosečnost i zato se strategija poslovne pobede zasniva na principu da tvoj proizvod ili usluga uvek budu malo bolji od ostalih na svetskom tržištu`, ovako je Ferbanks pre godinu dana na Harvardu ubeđivao u svoju teoriju konkurentnosti grupu srpskih poslovnih ljudi. Nedavnu posetu Srbiji iskoristio je da proveri jesu li ga neki od njih poslušali i da dodatnim savetima pomogne razvoju konkurentne privrede. Inače, na Ferbanksovoj teoriji o nacionalnoj konkurentnosti zasniva se i program razvoja konkurentne privrede u Srbiji koji podržava Američka agencija za međunarodni razvoj (USAID). Knjiga Oranje mora počinje pitanjem: `Zašto je državama u razvoju toliko teško da većini svojih građana omoguće da budu bogati?` A zatim sledi i odgovor: `Razlog leži u tome što je tradicionalni način takmičenja manjkav i lideri zemalja u razvoju moraju pronaći nove načine nadmetanja u globalnoj ekonomiji.` Obraćajući se prošle nedelje u Beogradu grupi poslovnih ljudi okupljenih oko Nacionalnog saveta za konkurentnost, Majkl Ferbanks zagovarao je tezu radikalnog raskida sa nasleđenim obrascima nekonkurentnog ponašanja iz prošlosti. Majkl Ferbanks govori za `Vreme` o novom modelu ekonomskog takmičenja koji podrazumeva drugačiju ulogu političkih lidera, promenu mentalne matrice, organizovanje firmi u klastere (udruženja) i usredsređivanja na cilj kroz takozvani prosperitetni događaj. `VREME`: Kako biste objasnili pojam prosperitetnog događaja? MAJKL FERBANKS: Sadašnji model poslovanja u Srbiji zasniva se na izvozu jednostavnih proizvoda čija se proizvodnja bazira na niskoj ceni rada, plodnom zemljištu, beneficijama Vlade i suncu. Kada tako radite, onda inostrani potrošač dobija svu korist, a deoničar-vlasnik malo zarađuje i radnici loše prolaze. To je model koji postoji ovde u Srbiji. Ali, ako vam model poslovanja glasi – `konkurisaću na svetskom tržištu svojom pameću, dobrom distributivnom mrežom, lepom ambalažom, novim brendom, kvalitetnijim odnosom sa krajnjim korisnikom` – tada deoničar dobija jednaku vrednost kao i kupac, a deo te vrednosti dobijaju i radnici, jer tada udeo radnika u tim `pravilima druge vrednosti` postaje mnogo važniji. To je prosperitetni događaj. U njemu svi dobro prolaze: i kupac i vlasnik i radnik. Da li ste, boraveći u Srbiji, videli u nekim kompanijama primere prosperitetnog događaja? Počinju da se pojavljuju i ja sam zadovoljan zbog toga. Čini mi se da Fresh&Co, kompanija za preradu voća ima sve izglede da to ostvari. Oni imaju divan proizvod, veoma visoku cenu, ostvaruju zaradu, otplaćuju svoj dug veoma brzo i kažu da deo koristi uživaju i radnici. To je odlična kompanija, jer su uzeli jednostavan proizvod poput maline koja je proizvod sunca i zemljišta i nastavili da u njega dodaju vrednost lepom bocom, kvalitetnom distribucijom, fokusom na tržište i na tome zarađuju. Veoma sam zadovoljan jer smo, čini mi se, našli takve dve, tri kompanije u kojima se to događa, što dokazuje da je prosperitetni događaj moguć i u Srbiji. Šta bi Srbija trebalo da učini da ima pet hiljada kompanija kao što je Fresh&Co? To je pravo pitanje. Prvo što vam je potrebno su pametni novinari koji će o tome pisati, jer je potrebno da od ovakvih kompanija učinimo uzore za mnoge ljude. Privredni razvoj nije makroekonomska pojava. Ekonomski razvoj je sociološki fenomen, a to znači da kada ljudi vide da su drugi uspešni i oni će pokušati da to učine. Problem u Srbiji je što kada je čovek uspešan, automatski se pretpostavlja da je i korumpiran. Tu pojavu je veoma važno razjasniti: tačno je da su korumpirani ljudi bogati, ali nisu svi bogataši korumpirani. Problem je što Srbi to ne shvataju. I deo političke elite u Srbiji zastupa tu tezu. Koliko je to veliki problem za zemlju u tranziciji? E, pa to je pogrešno i takvi političari nisu od velike pomoći. Ako ste korumpirani imate tendenciju da budete bogati, ali ako ste bogati nemate tendenciju ka korupciji. I ako Srbija ne shvati tu razliku, neće imati uzore. A pozitivni uzori su vam potrebni da biste izveli promene. Mediji su prilično loši u stvaranju uzora jer i oni veruju u loše stvari. Ukoliko je to preovlađujuće uverenje, onda za Srbiju nema nade. Jer, do promena ne može doći bez uzora. To je sociološka pojava, ne ekonomska. U aprilu 2003. godine na Harvardu ste kao dobru vest konstatovali da Srbija izlazi iz krize i ocenili da je idealnotipski slučaj za brzi ekonomski oporavak. U februaru 2004. loša vest je: Srbija je još u krizi… Nema sumnje. To je politička kriza i ponekad je državama potrebno da padnu jako nisko i osete krizu pre nego što se promene i krenu na gore. Srbija, nažalost, ima ogroman kapacitet da bude u krizi, a da se ne promeni. Ima strahovit potencijal da oseća bol, a da se ne menja. To je neverovatno. U Srbiji, među bogobojažljivim svetom, postoji izreka `trpen–spasen`… Oprostite, to je glupo. Važno je pronaći korelaciju između kulturnih obrazaca i ekonomskog prosperiteta. Ali, to je posebna tema koju bi trebalo istraživati. Problem Srbije je, između ostalog, što nema razvijen privatni sektor, što on nije preovlađujući i što je državna svojina još veoma jaka… Odgovornost za inovacije i stvaranje prosperiteta leži na privatnom sektoru. Nema sumnje da ukoliko Vlada bude glavni ekonomski strateg, Srbija će biti siromašna zemlja. Vraćam se opet na Harvard. U aprilu 2003. godine rekli ste da ako je Vlada `tata`, to je kao da svi u porodici puše marihuanu… Tako je, imate dobro pamćenje `Pušimo marihuanu i gojimo se`, to su bile moje reči. I upravo to se događa u Srbiji. Prošetao sam ulicama Beograda, ljudi su fatalistički raspoloženi, obožavaju prošlost i to ne skorašnju, već onu od pre hiljadu godina. Ne verujete u sopstvenu predodređenost, ne verujete jedni drugima i tu su istinski problemi. To je sociološka pojava. Ako mi postavite pitanje o strategiji poslovanja, ja ću vam reći koja je ispravna. Strategiju poslovanja nije teško napraviti. Ono što je teško je menjanje mentalnog sklopa građana i države i zato su novinari važniji od poslovnih stratega. Pre dva meseca u predizbornoj kampanji najčešće obećanje koje su srpski političari davali biračima bilo je da će povećati zarade. Oni koji su to obećavali, dobili su najviše glasova. Izborni pobednici obećavali su građanima manje bolnu tranziciju. Ima li leka za Srbiju? Mislim da su sreća i zadovoljstvo prosečnog građanina u direktnoj korelaciji sa prosperitetom. A prosperitet će ili doći od privatnog sektora ili ga uopšte neće biti. Dok god političari budu birani zahvaljujući preteranim obećanjima, za građane neće biti dobro. Ali, mislim da je pravedno reći da Srbi imaju vođe kakve zaslužuju. Koji su uslovi potrebni da Srbija postane prosperitetna zemlja? Prvi je opredeljenje vaših kompanija i vaše zemlje da ostvare već spominjani prosperitetni događaj. Zatim da firme pronađu klaster (udruženje) kome pripadaju i da znaju u kom delu poslovanja im je potrebna podrška državnog sektora. I na kraju, moraju da usmere energiju na stvari koje mogu da kontrolišu: da uče potrošače, da poboljšavaju proizvod, da investiraju u ljudski potencijal. Primenjujući vašu teoriju konkurentnosti u Srbiji je, uz pomoć USAID–a, formirano nekoliko klastera, odnosno udruženja proizvođača. Proizvođači voća i nameštaja zajednički nastupaju na evropskim sajmovima, a pojedine firme počele su da izvoze voće i u Sjedinjene Američke Države. Šta još USAID može da učini za srpsku privredu podržavajući klastere kao model za povećanje konkurentnosti? Kao najvažnije treba da tražimo da USAID nastavi ovako da radi i sledećih deset do dvadeset godina, na duge staze. Jer, ovo je vrsta promena koje se dešavaju veoma sporo, ali su veoma pozitivne, uvek su pozitivne. To su pomaci korak po korak. Nacionalna strategija koju pokušava da promoviše Nacionalni savet za konkurentnost prilika je da se u Srbiji povežu preduzetnici, civilni i državni sektor i tako poboljša takmičarski duh srpske privrede. Da li je to ispravan put? Bojim se da Savet nije dovoljno glasan ili dovoljno aktivan. Sa Vladom čiji se glas još ne čuje, pojavila se prilika da Savet preuzme tu ulogu. To je bila ogromna šansa da Savet napravi veliku stvar, ali nažalost nije uspelo. Koliko je realno očekivati da Savet preuzme vodeću ulogu u vreme političke nestabilnosti? Mislim da je od ključnog značaja za uspeh Srbije da Savet bude aktivniji i glasniji. Nema sumnje da ekonomski rast proizilazi iz zdravih organizacija civilnog društva. To je ono što je Srbiji potrebnije sada više nego ikada pre, jer je Vlada slaba, privatni sektor je slab. Isto važi i za štampane medije. Vreme je da neko iz novina počne da se bavi ovom temom i uvek je iznova objašnjava. U novinama u Srbiji ključni su naslovi sa katastrofičnim porukama… Ponekad mislim da se novinari plaše da budu optimisti. Da će ih javnost, ili još gore njihovi pretpostavljeni, kritikovati zbog optimizma. Veoma je važno za zemlju da se pozitivne poruke nađu na naslovnim stranama novina. Imali ste, na primer, odličnu priču o klasteru za nameštaj koji je imao prezentaciju na sajmu u Kelnu i svi proizvođači su se vratili zadovoljni jer će imati nove poslove. Sjajan je i način na koji su oni međusobno sarađivali na tom Sajmu i potpuno nesebično pomagali jedni drugima da se prikažu u najboljem svetlu. Ali, na pres konferenciju posvećenoj toj temi došla su četiri novinara, a vest je objavljena u dnu neke nevažne strane. Nažalost. A ta tema je izuzetno važna jer treba pokazati na koji se način srpske kompanije takmiče kao i da je to apsolutno neophodno za prosperitet svih građana. Šta vam treba Novinske agencije prenele su da ste na beogradskoj pres konferenciji izjavili da smo svi u Srbiji previše obuzeti privatizacijom? Privatizacija nije odgovor za sve. Nije bitno u čijem je vlasništvu neka kompanija. Pitanje je da li je ona konkuretna, da li ostvaruje zaradu, da li su joj proizvodi dobri, donosi li novac i da li dobro plaća radnike. Nebitno je da li je državna ili privatna, već koliko je dobra. Ali, treba reći da privatno vlasništvo obično poboljšava šanse da će neka kompanija biti bolja. Svetska banka i MMF su vam obećali da će sve biti dobro ukoliko privatizujete, demokratizujete, stabilizujete i liberalizujete. I pogrešili su. Greše. Jedino što je potrebno da uradite jeste da napravite velike i odlične kompanije. Ali, velike kompanije ne padaju sa neba.

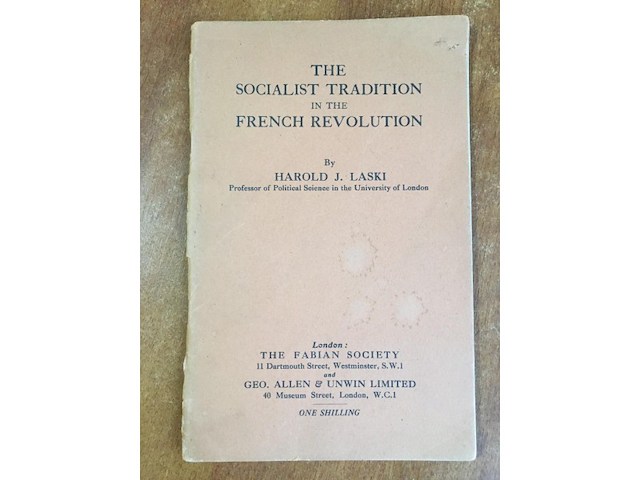

Harold Laski THE SOCIALIST TRADITION IN THE FRENCH REVOLUTION 1930 Retko Lepo očuvano Socijalistička tradicija u francuskoj revoluciji Harold Joseph Laski (30 June 1893 – 24 March 1950) was an English political theorist and economist. He was active in politics and served as the chairman of the British Labour Party from 1945 to 1946 and was a professor at the London School of Economics from 1926 to 1950. He first promoted pluralism by emphasising the importance of local voluntary communities such as trade unions. After 1930, he began to emphasize the need for a workers` revolution, which he hinted might be violent.[3] Laski`s position angered Labour leaders who promised a nonviolent democratic transformation. Laski`s position on democracy-threatening violence came under further attack from Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the 1945 general election, and the Labour Party had to disavow Laski, its own chairman.[4] Laski was one of Britain`s most influential intellectual spokesmen for Marxism in the interwar years.[citation needed] In particular, his teaching greatly inspired students, some of whom later became leaders of the newly independent nations in Asia and Africa. He was perhaps the most prominent intellectual in the Labour Party, especially for those on the hard left who shared his trust and hope in Joseph Stalin`s Soviet Union.[5] However, he was distrusted by the moderate Labour politicians, who were in charge[citation needed] such as Prime Minister Clement Attlee, and he was never given a major government position or a peerage. Born to a Jewish family, Laski was also a supporter of Zionism and supported the creation of a Jewish state.[6] Early life[edit] He was born in Manchester on 30 June 1893 to Nathan and Sarah Laski. Nathan Laski was a Lithuanian Jewish cotton merchant from Brest-Litovsk in what is now Belarus[7] and a leader of the Liberal Party, while his mother was born in Manchester to Polish Jewish parents.[8] He had a disabled sister, Mabel, who was one year younger. His elder brother was Neville Laski (the father of Marghanita Laski), and his cousin Neville Blond was the founder of the Royal Court Theatre and the father of the author and publisher Anthony Blond.[9] Harold attended the Manchester Grammar School. In 1911, he studied eugenics under Karl Pearson for six months at University College London (UCL). The same year, he met and married Frida Kerry, a lecturer of eugenics. His marriage to Frida, a Gentile and eight years his senior, antagonised his family. He also repudiated his faith in Judaism by claiming that reason prevented him from believing in God. After studying for a degree in history at New College, Oxford, he graduated in 1914. He was awarded the Beit memorial prize during his time at New College.[10] In April 1913, in the cause of women`s suffrage, he and a friend planted an explosive device in the men`s lavatory at Oxted railway station, Surrey: it exploded, but caused only slight damage.[11] Laski failed his medical eligibility tests and so missed fighting in World War I. After graduation, he worked briefly at the Daily Herald under George Lansbury. His daughter Diana was born in 1916.[10] Career[edit] Academic career[edit] In 1916, Laski was appointed as a lecturer of modern history at McGill University in Montreal and began to lecture at Harvard University. He also lectured at Yale in 1919 to 1920. For his outspoken support of the Boston Police Strike of 1919, Laski received severe criticism. He was briefly involved with the founding of The New School for Social Research in 1919,[12] where he also lectured.[13] Laski cultivated a large network of American friends centred at Harvard, whose law review he had edited. He was often invited to lecture in America and wrote for The New Republic. He became friends with Felix Frankfurter, Herbert Croly, Walter Lippmann, Edmund Wilson, and Charles A. Beard. His long friendship with Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. was cemented by weekly letters, which were later published.[14] He knew many powerful figures and claimed to know many more. Critics have often commented on Laski`s repeated exaggerations and self-promotion, which Holmes tolerated. His wife commented that he was `half-man, half-child, all his life`.[15] Laski returned to England in 1920 and began teaching government at the London School of Economics (LSE). In 1926, he was made professor of political science at the LSE. Laski was an executive member of the socialist Fabian Society from 1922 to 1936. In 1936, he co-founded the Left Book Club along with Victor Gollancz and John Strachey. He was a prolific writer and produced a number of books and essays throughout the 1920s and the 1930s.[16] At the LSE in the 1930s, Laski developed a connection with scholars from the Institute for Social Research, now more commonly known as the Frankfurt School. In 1933, with almost all the Institute`s members in exile, Laski was among a number of British socialists, including Sidney Webb and RH Tawney, who arranged for the establishment of a London office for the Institute`s use. After the Institute moved to Columbia University in 1934, Laski was one of its sponsored guest lecturers invited to New York.[17] Laski also played a role in bringing Franz Neumann to join the Institute. After fleeing Germany almost immediately after Adolf Hitler`s rise to power, Neumann did graduate work in political science under Laski and Karl Mannheim at the LSE and wrote his dissertation on the rise and fall of the rule of law. It was on Laski`s recommendation that Neumann was then invited to join the Institute in 1936.[18] Teacher[edit] Laski was regarded as a gifted lecturer, but he would alienate his audience by humiliating those who asked questions. However, he was liked by his students, and was especially influential among the Asian and African students who attended the LSE.[15] Describing Laski`s approach, Kingsley Martin wrote in 1968: He was still in his late twenties and looked like a schoolboy. His lectures on the history of political ideas were brilliant, eloquent, and delivered without a note; he often referred to current controversies, even when the subject was Hobbes`s theory of sovereignty.[19] Ralph Miliband, another of Laski`s student, praised his teaching: His lectures taught more, much more than political science. They taught a faith that ideas mattered, that knowledge was important and its pursuit exciting.... His seminars taught tolerance, the willingness to listen although one disagreed, the values of ideas being confronted. And it was all immense fun, an exciting game that had meaning, and it was also a sieve of ideas, a gymnastics of the mind carried on with vigour and directed unobtrusively with superb craftsmanship. I think I know now why he gave himself so freely. Partly it was because he was human and warm and that he was so interested in people. But mainly it was because he loved students, and he loved students because they were young. Because he had a glowing faith that youth was generous and alive, eager and enthusiastic and fresh. That by helping young people he was helping the future and bringing nearer that brave world in which he so passionately believed.[20] Ideology and political convictions[edit] Laski`s early work promoted pluralism, especially in the essays collected in Studies in the Problem of Sovereignty (1917), Authority in the Modern State (1919), and The Foundations of Sovereignty (1921). He argued that the state should not be considered supreme since people could and should have loyalties to local organisations, clubs, labour unions and societies. The state should respect those allegiances and promote pluralism and decentralisation.[21] Laski became a proponent of Marxism and believed in a planned economy based on the public ownership of the means of production. Instead of, as he saw it, a coercive state, Laski believed in the evolution of co-operative states that were internationally bound and stressed social welfare.[22] He also believed that since the capitalist class would not acquiesce in its own liquidation, the co-operative commonwealth was not likely to be attained without violence. However, he also had a commitment to civil liberties, free speech and association and representative democracy.[23] Initially, he believed that the League of Nations would bring about an `international democratic system`. However, from the late 1920s, his political beliefs became radicalised, and he believed that it was necessary to go beyond capitalism to `transcend the existing system of sovereign states`. Laski was dismayed by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 and wrote a preface to the Left Book Club collection criticising it, titled Betrayal of the Left.[24] Between the beginning of World War II in 1939 and the Attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, which drew the United States into the war, Laski was a prominent voice advocating American support for the Allies, became a prolific author of articles in the American press, frequently undertook lecture tours in the US and influenced prominent American friends including Felix Frankfurter, Edward R. Murrow, Max Lerner, and Eric Sevareid.[25] In his last years, he was disillusioned by the Cold War and the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d`état.[10][16][23] George Orwell described him thus: `A socialist by allegiance, and a liberal by temperament`.[15] Laski tried to mobilise Britain`s academics, teachers and intellectuals behind the socialist cause, the Socialist League being one effort. He had some success but that element typically found itself marginalised in the Labour Party.[26] Zionism and anti-Catholicism[edit] Laski was always a Zionist at heart and always felt himself a part of the Jewish nation, but he viewed traditional Jewish religion as restrictive.[6] In 1946, Laski said in a radio address that the Catholic Church opposed democracy,[27] and said that `it is impossible to make peace with the Roman Catholic Church. It is one of the permanent enemies of all that is decent in the human spirit`.[28] In his final years he became critical of what he saw as extremism in Israel at the outbreak of the 1947-48 Civil War, arguing that they had not prevailed `upon an indefensible group among them to desist from using indefensible means for an end to which they were never proportionate.`[29] Political career[edit] Laski`s main political role came as a writer and lecturer on every topic of concern to the left at that time, including socialism, capitalism, working conditions, eugenics,[30] women`s suffrage, imperialism, decolonisation, disarmament, human rights, worker education and Zionism. He was tireless in his speeches and pamphleteering and was always on call to help a Labour candidate. In between, he served on scores of committees and carried a full load as a professor and advisor to students.[31] Laski plunged into Labour Party politics on his return to London in 1920. In 1923, he turned down the offer of a Parliament seat and cabinet position by Ramsay MacDonald and also a seat in the Lords. He felt betrayed by MacDonald in the crisis of 1931 and decided that a peaceful, democratic transition to socialism would be blocked by the violence of the opposition. In 1932, Laski joined the Socialist League, a left-wing faction of the Labour Party.[32] In 1937, he was involved in the failed attempt by the Socialist League in co-operation with the Independent Labour Party (ILP) and the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) to form a Popular Front to bring down the Conservative government of Neville Chamberlain. In 1934 to 1945, he served as an alderman in the Fulham Borough Council and also the chairman of the libraries committee. In 1937, the Socialist League was rejected by the Labour Party and folded. He was elected as a member of the Labour Party`s National Executive Committee and he remained a member until 1949. In 1944, he chaired the Labour Party Conference and served as the party`s chair in 1945 to 1946.[21] Declining role[edit] During the war, he supported Prime Minister Winston Churchill`s coalition government and gave countless speeches to encourage the battle against Nazi Germany. He suffered a nervous breakdown brought about by overwork. During the war, he repeatedly feuded with other Labour figures and with Churchill on matters great and small. He steadily lost his influence.[33] In 1942, he drafted the Labour Party pamphlet The Old World and the New Society calling for the transformation of Britain into a socialist state by allowing its government to retain wartime central economic planning and price controls into the postwar era.[34] In the 1945 general election campaign, Churchill warned that Laski, as the Labour Party chairman, would be the power behind the throne in an Attlee government. While speaking for the Labour candidate in Nottinghamshire on 16 June 1945, Laski said, `If Labour did not obtain what it needed by general consent, we shall have to use violence even if it means revolution`. The next day, accounts of Laski`s speech appeared, and the Conservatives attacked the Labour Party for its chairman`s advocacy of violence. Laski filed a libel suit against the Daily Express newspaper, which backed the Conservatives. The defence showed that over the years Laski had often bandied about loose threats of `revolution`. The jury found for the newspaper within forty minutes of deliberations.[35] Attlee gave Laski no role in the new Labour government. Even before the libel trial, Laski`s relationship with Attlee had been strained. Laski had once called Attlee `uninteresting and uninspired` in the American press and even tried to remove him by asking for Attlee`s resignation in an open letter. He tried to delay the Potsdam Conference until after Attlee`s position was clarified. He tried to bypass Attlee by directly dealing with Churchill.[16] Laski tried to pre-empt foreign policy decisions by laying down guidelines for the new Labour government. Attlee rebuked him: You have no right whatever to speak on behalf of the Government. Foreign affairs are in the capable hands of Ernest Bevin. His task is quite sufficiently difficult without the irresponsible statements of the kind you are making ... I can assure you there is widespread resentment in the Party at your activities and a period of silence on your part would be welcome.[36] Though he continued to work for the Labour Party until he died, he never regained political influence. His pessimism deepened as he disagreed with the anti-Soviet policies of the Attlee government in the emerging Cold War, and he was profoundly disillusioned with the anti-Soviet direction of American foreign policy.[21] Death[edit] Laski contracted influenza and died in London on 24 March 1950, aged 56.[21] Legacy[edit] Laski`s biographer Michael Newman wrote: Convinced that the problems of his time were too urgent for leisurely academic reflection, Laski wrote too much, overestimated his influence, and sometimes failed to distinguish between analysis and polemic. But he was a serious thinker and a charismatic personality whose views have been distorted because he refused to accept Cold War orthodoxies.[37] Blue plaque, 5 Addison Bridge Place, West Kensington, London Columbia professor Herbert A. Deane has identified five distinct phases of Laski`s thought that he never integrated. The first three were pluralist (1914–1924), Fabian (1925–1931), and Marxian (1932–1939). There followed a `popular-front` approach (1940–1945), and in the last years (1946–1950) near-incoherence and multiple contradictions.[38] Laski`s long-term impact on Britain is hard to quantify. Newman notes that `It has been widely held that his early books were the most profound and that he subsequently wrote far too much, with polemics displacing serious analysis.`[21] In an essay published a few years after Laski`s death, Professor Alfred Cobban of University College London observed: Among recent political thinkers, it seems to me that one of the very few, perhaps the only one, who followed the traditional pattern, accepted the problems presented by his age, and devoted himself to the attempt to find an answer to them was Harold Laski. Though I am bound to say that I do not agree with his analysis or his conclusions, I think that he was trying to do the right kind of thing. And this, I suspect, is the reason why, practically alone among political thinkers in Great Britain, he exercised a positive influence over both political thought and action.[39] Laski had a major long-term impact on support for socialism in India and other countries in Asia and Africa. He taught generations of future leaders at the LSE, including India`s Jawaharlal Nehru. According to John Kenneth Galbraith, `the centre of Nehru`s thinking was Laski` and `India the country most influenced by Laski`s ideas`.[23] It is mainly due to his influence that the LSE has a semi-mythological status in India.[citation needed] He was steady in his unremitting advocacy of the independence of India. He was a revered figure to Indian students at the LSE. One Prime Minister of India[who?] said `in every meeting of the Indian Cabinet there is a chair reserved for the ghost of Professor Harold Laski`.[40][41] His recommendation of K. R. Narayanan (later President of India) to Nehru (then Prime Minister of India), resulted in Nehru appointing Narayanan to the Indian Foreign Service.[42] In his memory, the Indian government established The Harold Laski Institute of Political Science in 1954 at Ahmedabad.[21] Speaking at a meeting organised in Laski`s memory by the Indian League at London on 3 May 1950, Nehru praised him as follows: It is difficult to realise that Professor Harold Laski is no more. Lovers of freedom all over the world pay tribute to the magnificent work that he did. We in India are particularly grateful for his staunch advocacy of India`s freedom, and the great part he played in bringing it about. At no time did he falter or compromise on the principles he held dear, and a large number of persons drew splendid inspiration from him. Those who knew him personally counted that association as a rare privilege, and his passing away has come as a great sorrow and a shock.[43] Laski also educated the outspoken Chinese intellectual and journalist Chu Anping at LSE. Anping was later prosecuted by the Chinese Communist regime of the 1960s.[44] Laski was an inspiration for Ellsworth Toohey, the antagonist in Ayn Rand`s novel The Fountainhead (1943).[45] The posthumously published Journals of Ayn Rand, edited by David Harriman, include a detailed description of Rand attending a New York lecture by Laski, as part of gathering material for her novel, following which she changed the physical appearance of the fictional Toohey to fit that of the actual Laski.[46] Laski had a tortuous writing style. George Orwell, in his 1946 essay `Politics and the English Language` cited, as his first example of poor writing, a 53-word sentence with five negatives from Laski`s `Essay in Freedom of Expression`: `I am not, indeed, sure whether it is not true to say that the Milton who once seemed not unlike a seventeenth-century Shelley had not become, out of an experience ever more bitter in each year, more alien (sic) to the founder of that Jesuit sect which nothing could induce him to tolerate.` (Orwell parodied it with ` A not unblack dog was chasing a not unsmall rabbit across a not ungreen field.`) However, 67 of the Labour MPs elected in 1945 had been taught by Laski as university students, at Workers` Educational Association classes or on courses for wartime officers.[47] When Laski died, the Labour MP Ian Mikardo commented: `His mission in life was to translate the religion of the universal brotherhood of man into the language of political economy.`[48] Partial bibliography[edit] Basis of Vicarious Liability 1916 26 Yale Law Journal 105 Studies in the Problem of Sovereignty 1917 Authority in the Modern State 1919, ISBN 1-58477-275-1 Political Thought in England from Locke to Bentham 1920 The Foundations of Sovereignty, and other essays 1921 Karl Marx 1921 The state in the new social order 1922 The position of parties and the right of dissolution 1924 A Grammar of Politics, 1925 Socialism and freedom. Westminster: The Fabian Society. 1925. The problem of a second chamber 1925 Communism, 1927 The British Cabinet : a study of its personnel, 1801-1924 1928 Liberty in the Modern State, 1930 `The Dangers of Obedience and Other Essays` 1930 The limitations of the expert 1931 Democracy in Crisis 1933 The State in Theory and Practice, 1935, The Viking Press The Rise of European Liberalism: An Essay in Interpretation, 1936 US title: The Rise of Liberalism: The Philosophy of a Business Civilization, 1936 The American Presidency, 1940 Where Do We Go From Here? A Proclamation of British Democracy 1940 Reflections on the Revolution of our Time , 1943 Faith, Reason, and Civilisation, 1944 The American Democracy, 1948, The Viking Press Communist Manifesto: Socialist Landmark: A New Appreciation Written for the Labour Party (1948)[49] sloboda u modernoj državi politička gramatika